Art World Undercover #2: Tishan Hsu at Miguel Abreu Gallery, by Adam Lehrer

Between projects, Lehrer goes back undercover into the ideological ghetto that is the art world. In the 2nd entry of this column, he finds techno-opposition in the body horrific art of Tishan Hsu

I’m looking at a print by the photographer Rosalind Fox Solomon. It depicts a man dressed up in a costumed uniform resembling that of the soldiers of the Alamo as he stands inside a room; the camera however is positioned outside the room and photographing the faux soldier at a vantage point in the hall outside, and just next to the door which is swung all the way open is a child’s girl doll that leaves a perversely uncanny sensation with you upon seeing it. The soldier, it would seem, has succumbed to his fantasy world locked away inside of his living quarters. I’m empathizing with this figure’s divorce from reality while sitting on a bench in Ahearn Park and gathering myself. Reality itself is so fucking fantastical, and contradictory – why not hide away? Why not create your own? Why not just pretend that the world within your head is also the world exterior to you? What does it matter, really? Maybe the make believe soldier is freer than I could ever hope to be?

“The fact that an event has taken place is no proof of its valid occurrence,” once wrote one of the Counter-Agency’s founders JG Ballard. Looking at this photograph just a bit more, I wonder if it’s possible that just because an event has not taken place it is no kind of proof of it’s non-occurrence? I digress…

I’m thinking to myself: “I too know what it’s like to pretend,” as Eyeless in Gaza’s “The Eyes of Beautiful Losers” whispers into my ears. I change the album playing on my phone to The Caretaker’s Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom. I don’t want to be cliché, but I reckon it’s worthwhile for Leyland Kirby’s eerie vintage ballroom recordings to kickstart my contemplation of the future that we’ve been robbed of. I open an encrypted message from my handler. My mission, ambiguous as it might be, is to embed myself into the art world and locate and celebrate the art that might free us to seize our future. Mental and spiritual liberation begins here. I must infiltrate the enemy, know the enemy, and identify my assets and allies hiding in plain sight within the institutions of the enemy, and recruit them into the Counter-Agency of the Avant-Garde. The encrypted message directs me to Miguel Abreu gallery, to assess the value in the possible recruitment of Tishan Hsu, the now quite old (b. 1951) postmodern artist currently the subject of a solo exhibition at the space: skin-screen-grass.

Hsu is an artist that I am more than familiar with; in fact I’ve long been mesmerized with the postmodern, techno-dystopian, Cronenbergian aesthetic he works within every bit as much as I’ve been mystified by the ideological subtext encrypted within his work. I take my earbuds out, and ask myself: “Is Hsu one of us? Can he be trusted?” I start walking due northwest to the gallery.

I’m wearing a vintage Carhartt jacket in light khaki paired with chinos of a darker khaki color, my brown shitkicker boots, and a black corduroy shirt. My hair has grown out considerably since I last bicked it, and I feel pride in the fulness and color that it has retained whilst entering my mid-’30s (I hate to call it middle age, because as a highly trained and well-exercised Counter-Agent, I still feel 25). I can’t think of what to listen to, but the weather is dank. It’s cloudy but not raining, and an ominous chill saturates the air, but I’m sweating. I find myself listening to Phương Tâm, and my hips begin to swivel to the sounds of her Eastern-inflected surf as I walk forward. “Such astounding music,” I think, and prepare to enter the gallery. Eldridge St. is quiet save for a homeless man without any shoes on revealing hideous necrosis that has started to collapse his flesh around needle injection sites. Somehow, this feels like a darkly appropriate starting point for the exhibition.

Miguel Abreu Gallery requires one to take an elevator up to it on the fourth floor. I wipe the sweat from the temples of my forehead and crack my neck as the slow elevator moves upwards, before it opens the door and I am in the long hallway that enters the gallery. Towards my left, I walk by a young and attractive asian woman (at least I think she could be attractive, the surgical mask she’s wearing dilutes her beauty), look at her, raise my eyebrow, and smile in a practiced, coy manner that disarms the people who could potentially disrupt my mission. She nods, and smiles. My cheap diversionary seductive technique appears to have worked. I sign the guest notebook and notice the names of two friends — the artist Bradford Kessler and the curator Reilley Davidson — and the curator Bob Nickas. I wonder what it’s like to be them. I ask myself what it’d be like to simply enjoy art for what it is and not have to deconstruct it with a counter-ideological agenda. I walk towards the first installation of Tishan Hsu works in a space on my left. I enter the space.

The first piece I encounter, Blue Interface, is a massive blue inkjet print on aluminum emblazoned with the images of human mouths swirling back into the object surrounded by the illusion of nails hammered into the piece itself. In the center of the piece, red silicon is globbed into a formless shape, like a mound of dried blood. As ever, Hishan seems desperate to locate a pulse — a living flesh and blood vessel — at the heart of technology. But the only life force animating technology is that which has always driven economic forces: desire. Lyotard, of course, called it the libidinal economy. Hsu’s strange, body horrific art is easily read through Lyotard’s market jouissance as it manifests in the technological and the synthetic. I’ve long admired the artist’s refusal to allow his work to be absorbed into mainstream discourse — during an interview with the satanic NYT last year, when pressed about whether his pseudo-Cronenbergian forms are connected to the pandemic, he merely retorted: “I don’t know what the work is about, It just validates the unconscious” — but can he really be seen as an ally in the war of counter-intelligence? I need to analyze the body of work further.

I turn around, and opposite Blue Interface is a piece called Boating Scene 1,2,3. It’s a visually startling work of art that, much like the music of The Caretaker that I was listening to not but one hour ago, resembles the image of a memory hallucinated into a daydream. The UV cured inkjet is printed with a vintage photograph of what looks like a scene of East Asian people (Japanese, perhaps) riding in a row boat in some peaceful body of water around the mid-20th Century, or so.

Dragging my eye from the left to the right of the canvas, the image crackles, fades, and finally kaleidoscopically wobbles into the kind of disorienting visual that one experiences after exhaling a hit of DMT. The piece begs philosophical inquiry into the nature of late modern image production: perhaps digital technology doesn’t just change the way we capture and engage with images now, but also undermines and distorts the presentation of the captured images of the past. Hsu’s work, at its best, reverberates with violent contradictions. Violent contradictions were believed by Bataille to be the real face of the truth, and now I’m pondering the idea that perhaps it is Tishan Hsu that more than any working visual artist is attempting to give definable form to the colliding ideas and psychotic conflicts that define the contemporary world.

I’m deep in thought and writing notes on my iPhone. Before going to any of the screen printed canvases, I walk to the back of the gallery to look hard and close at the sculptural works on display. I put my headphones back in and put on a record by Rubber O Cement, a noisy spin-off of the Bay Area avant-garde institution Caroliner, hoping that the psychotic and nonsensical tones in my ears will make the delirium I’m experiencing in my head comparatively non-threatening. The sculptural piece, Phone-Breath-Bed, is mind-warping to look at. A piece of polycarbonate glass is in the shape of a hospital bed, and on top of it is silicone. Once an architectural student, the artist interprets the human body as architectural form – and like all architectural forms can be, Hsu understands that human bodies can be controlled and manipulated.

Where a human head would be as if perched on a pillow, the silicon is carefully shaped in the form of a human visage and, below that the same material alludes to the innards of a human torso. Beneath the polycarbonate, is another inkjet, and there are screenprints of human X-rays appropriately placed to where the hypothetical figure’s skeletal placements would be. And below the screen-prints is another mound of fleshy silicon. I find that James Woods’ mantra in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome — “Long Live the New Flesh —is looping in my mind, but I worry that the reference is too obvious and, if communicated, a bit hackneyed. Nevertheless, Hsu’s preoccupations with the body’s technological evolution cannot be understated. The piece suggests that technology liberates the human form, but only liberates it from its own natural ephemerality and into a perhaps even darker space of control. Transgenderism, transhumanism, transhistoricism, and so on. Only the nonsensical makes any kind of sense in the here and now. Technology allows the body to evolve, but perhaps it’s not supposed to. And yet, we have no choice. The techno-dystopic change is compulsory. Further to Hishan’s credit, the artist has no interest in making moral judgment upon this state of affairs. He merely sees the power of these all-encompassing tendencies, and gives it form.

It’s all too easy for me to be seduced by Hsu’s art. Aesthetically, it hits so hard. It reminds me of so much of the cultural productions that shaped and formed and psyopped me: Cronenberg, Ballard, Crash, Burroughs’ Nova Trilogy, Giger’s Xenomorphs, Baudrillard, William Gibson (revolting shitlib that he is), Samuel Delany, CCRU, The Terminator, and on and on. It’s ever difficult to maintain the analytical disposition of the agent as I confront Hsu’s beautiful colors, humanoid forms, blurred images, cyberpunk suggestions, and minimalist shapes. I slap my cheeks with both hands to gather myself and walk over to the piece that I had saved for last.

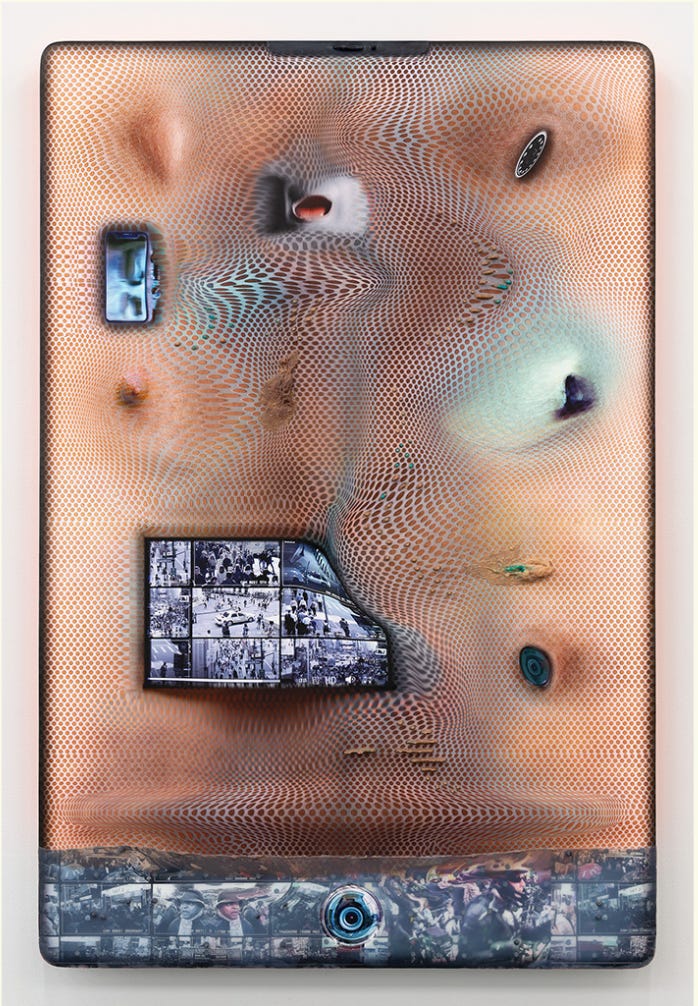

Watching 2 is psychedelic and hypnotic. The piece, with its screenprints of X-ray surveillance footage, perhaps alludes to the panopticon. The screenprint at the bottom of the work is a captured image of surveillance footage observing a Black Lives Matter protest. Now, here is where my mission gets interesting. The simple-minded and unquestioning liberal art critic might assume that Hsu is alluding to government surveillance’s overreach in its observation of peaceful protest. But my feeling as I look up and down at this work of art is that it’s more complicated than that. The protest is indeed being watched, but if the protest was actually a substantive threat to state power, why would it be allowed to blaze on unabated? The more interesting interpretation of the artwork is that Black Lives Matter is actually a part of not the panopticon, but the synopticon – that is, the many watching the few. Black Lives Matter support is all but compulsory in the United States. Who can forget that just two months after the pandemic lockdowns began, George Floyd was killed and the media and the Democratic Party suggested that protests — some peaceful and some devolving into blazing, violent riots — were perfectly OK to attend because, “Racism is the real pandemic.”

The techno surveillance state doesn’t just watch us, it demands we adhere to its dictums. It requires our participation in its psyops. Those who refuse, like me, are to be deplatformed, smeared, and turned into pariahs. The many (the techno-pharma state and its legions of useful morons) tirelessly observe the few (those who just fucking “prefer not to” as the recently useless Zizek once refrained). Is this what Tishan Hsu is thinking about with this stunning body of work? Who’s to say, really? But the mere fact that Hsu’s exhibition at Miguel Abreu gallery has demanded my contemplation over these difficult notions of the contemporary world is something to consider. That, undoubtedly, is reassuring.

I exit the gallery and take the elevator downstairs. It’s already dark outside at 5:15 pm, and the air has gone crisp and unwelcoming. I rub my hands together and blow the hot air of my breath into them before taking my phone out of my pocket. I leave an encrypted note to myself and my affiliates: “I can’t tell if Hsu is one of us, but his ideas might be useful to us yet.”

ILLUSTRATIONS:

1. Tishan Hsu [SPA] – to be titled (2021)

2. Photograph by Rosalind Fox Solomon

3. Tishan Hsu Watching 1 (2021) [detail]

4. Tishan Hsu Blue Interface (2019-’21)

5. Tishan Hsu Boating Scene 1.2.3, (2021)

5. Tishan Hsu Phone-Breath-Bed (2021)

6. Tishan Hsu Watching 1 (2021)