Art's Moral Fetish REDUXE

A Longer, Unedited transcript of Adam Lehrer's 2020 essay for Caesura Magazine

Introduction: Art’s Moral Fetish was initially published by Caesura Magazine in October of 2020. I wrote this in response to what I viewed as a hardening of reactionary disciplinary tactics that were being used by activist institutions in the wake of the George Floyd protests, and how that reactionary sentiment was bleeding into the arts. Roland Barthes once said that fascism wasn’t to take one’s right of speech away, but to take away one’s right to silence. Thus, I found myself suffocated by the endless artists posting #silenceisviolence hashtags. I wanted to comment on the disconnect between the political aesthetics of the art world (ie, hyper radical) and the reality of what those politics represented (ie, allegiance to left liberal political parties). For that moment in time, the art world accepted the idea that to be “radical” was to vote Democrat, and that to be a fascist was to vote Republican. I was disgusted by the lie that this represented, and disappointed with the artists I respected that reproduced that lie. So almost six months later, has this phenomenon shifted? In some ways, yes. There are less hash tags and less displays of reactionary discourse policing. But this also only proves my point: all the radical energy and the hashtags and the burnt cities only helped Joe Biden get elected. Nothing else changed, politically. This to me proves that wokeness and the art world version of it isn’t a real dissenting political ideology, but a near-authoritarian commitment to the version of the system that most flatters one’s own political economic interests. This is an essay about a disciplinarian petty bourgeoise creative class. I have a lot of versions of this essay, some very long. The one we published was about 2500 words. This version is about 6000. I have one that is 15000. There is a lot to say.

My only regret about the piece is its title. It’s a bit clunky, because as DC Miller pointed out to me in an email, the essay isn’t about morality so much as it’s about an ideology. But what I hoped the title would do is emphasize the idea that bourgeois morality has taken many forms in the last 200 years. But what is new about this version of it, is that bourgeois morality has taken the form of an ideology that was created by leftwing activists. “The left” is the dominant power structure and its increasingly arbitrary beliefs are the legitimizing ideology of that power structure. This has proven to be genius, because now there is no light and day between the system’s dissent and the dissent itself. It’s all one blob. The dissent is a vital part of the system, and the art world is an important aspect of how that useful dissent is communicated.

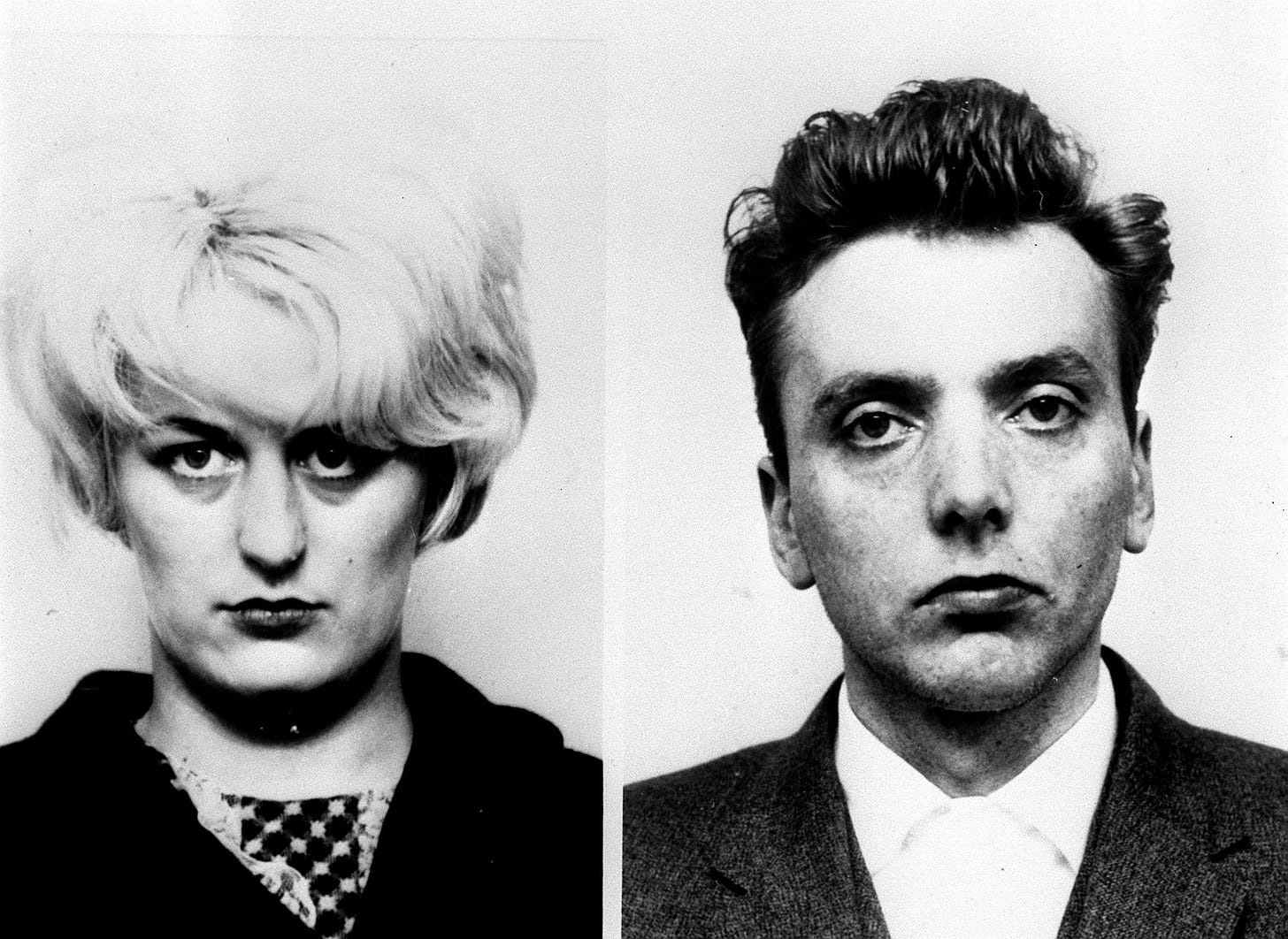

Morality and legality are decided chiefly by the prevailing ruling class in whatever geographical variant, not least because a collective morality is too unwieldy and difficult to maintain – Ian Brady, The Book of Janus [1]

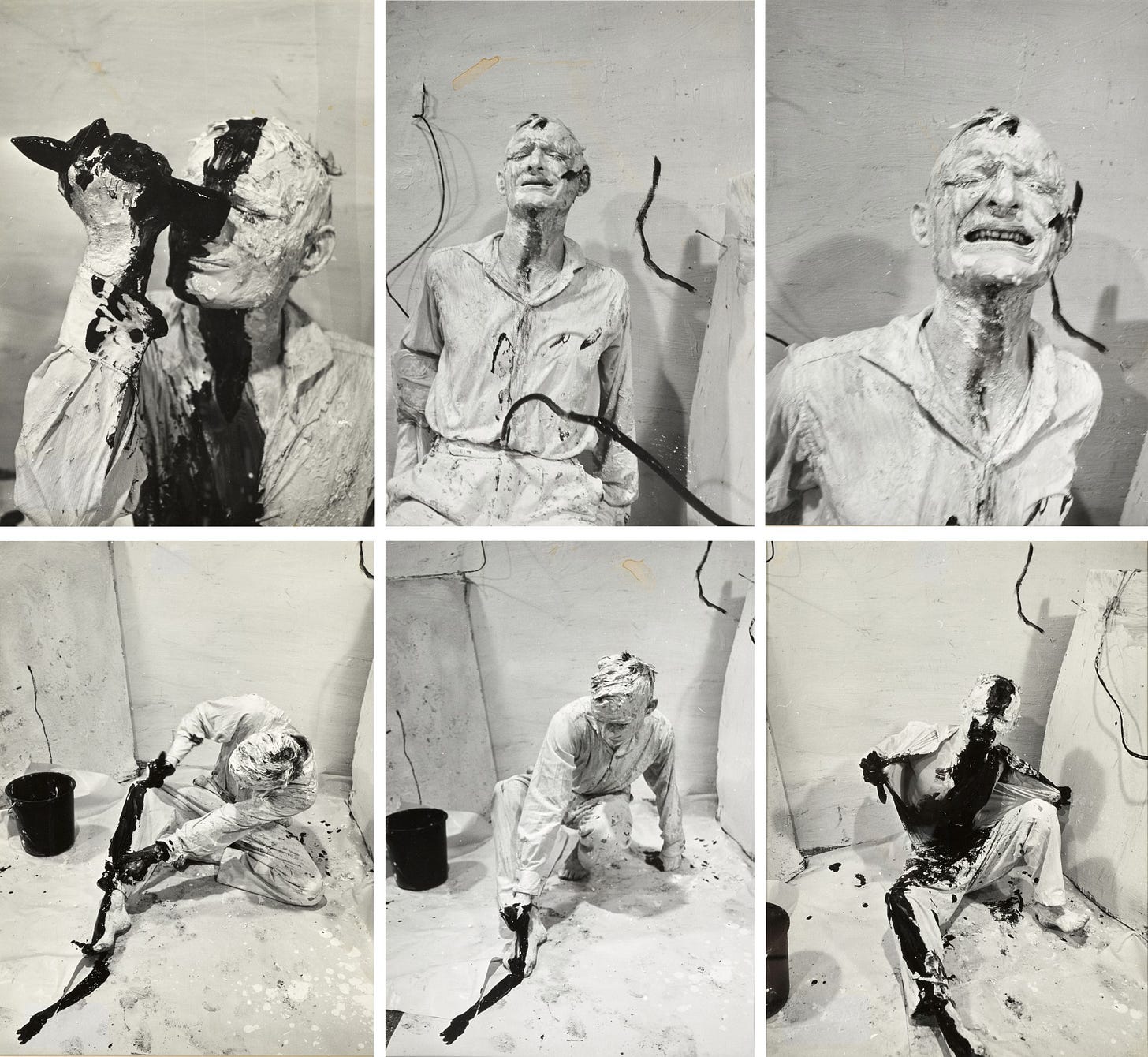

The British serial killer Ian Brady’s sentiment largely echoes the theory of moral relativism pioneered by Marquis de Sade. Regardless of what we think of Brady’s heinous crimes, it’s hard to argue with the pulse of his statement: of course the ruling class sets the parameters of societal morality. In the past, however, great artists sought to question, push back on, and expose where necessary the hypocrisies embedded within that morality. Louise Bourgeois’ embrace of the phallic object. The Viennese Aktionists’ rituals of Sadeian sadism and sexual catharsis. Honoré Daumier’s illustrative satires that depicted the members of the 19th Century French aristocracy as grotesque cretins. This oppositional role of the artist has vanished from the contemporary art world. There’s no more dissent, no more provocations that dare us to challenge our power structures. Instead, contemporary artists are more likely to both mirror and propagandize on behalf of the constructed morality of the ruling class more than effectively expose its faulty logics.

“How are you voting in 2020?” asks a yard sign image posted by Marilyn Minter to the artist’s Instagram on August 16. Your choices, according to the sign, are “Democrat” or “Fascist.” 3,359 accounts offered their support for this piece of bourgeois liberal sentiment by liking the post. “GREAT!!!” emphatically comments similarly renown feminist artist Judith Bernstein. Artist Marcel Dzama expressed his admiration for the post with an eloquent heart and raised fist emoji combination. The whole digital scene is nauseating, and its message is clear: this is the ideological window of acceptability. If you fall outside of it, you are suspect at best and fascist at worst. Art has long been visibly in a symbiotic relationship with bourgeois state power [2]. Nevertheless, there is something deeply unsettling about our supposedly “radical” artists manufacturing consent on behalf of one of our two entrenched capitalist parties. Neoliberalism necessitates the threat of something even more horrible than the present to justify itself as the status quo. In the early 2000s, public support for the status quo was secured through fear mongering radical Islamic terror. Now, the spectral threat is “fascism,” but Trump isn’t a fascist. He’s better interpreted as a symbol of the decline of American empire and global capitalism, but if we realized that we might stop voting for our real oppressors (the DNC is the security state, Silicon Valley and Wall Street). What Minter is doing here is what many artists are doing more broadly: using her platform as a major American artist to propagandize on behalf of the left side of capital. In the process, she’s not just manufacturing consent, but neutralizing art of its critical role. The cultural hegemony has shifted in the last 30 years to what we have now, an unholy union of Reaganite neoliberal economic policies with intersectional leftist tendencies and aesthetics. Artists, ever trapped in the banal culture wars of previous decades, are either incapable of detecting this shift or even worse, consciously regurgitating the reductive narratives of the left liberal elite. This phenomenon is vampirically exsanguinating the lifeblood of creativity itself: the freedom to challenge the orthodoxies of our culture, politics, and society. The freedom to make art untethered to the ideology of the regime.

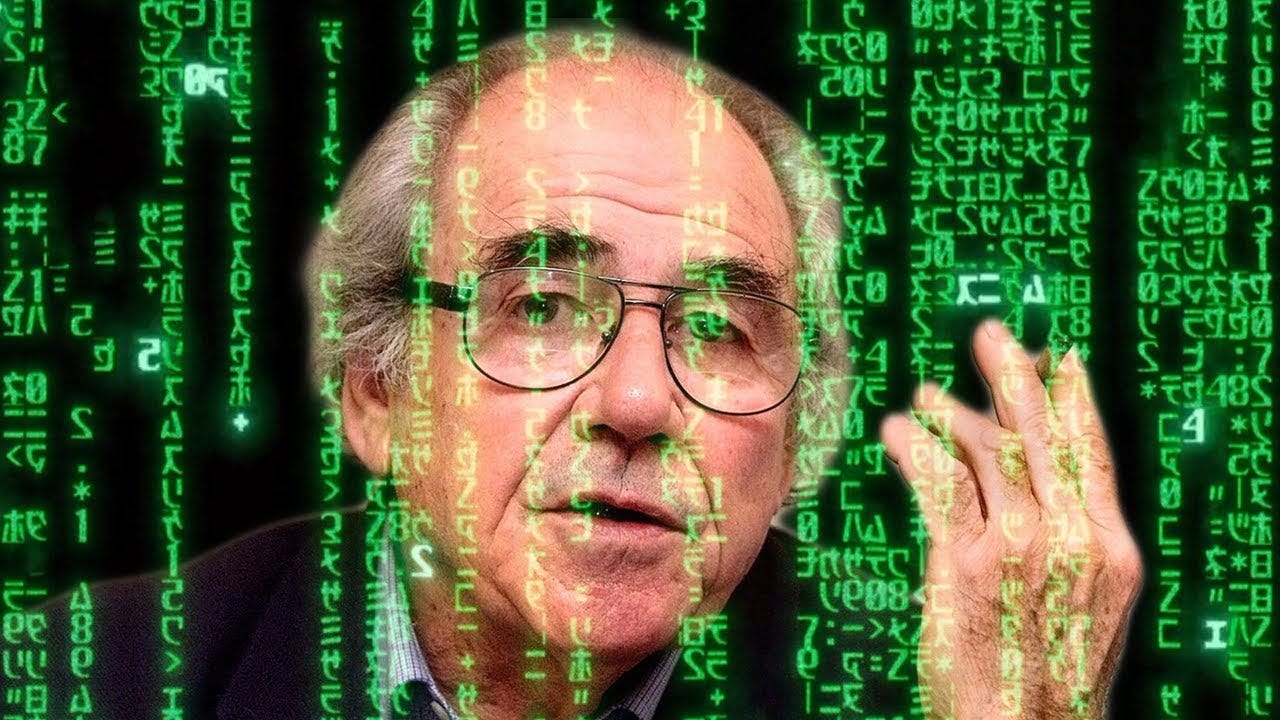

Baudrillard, of course, said in his 1996 essay “The Conspiracy of Art,” that art had no more reason to exist [3]. He declared art meaningless and, to use his chosen word, null. The philosopher believed that art had lost sight of its mystique through its divorce with “the desire of illusion” during the commercial explosion of the 1980s, when art was reduced to commodity. But if illusionism in art has found a “second life” as Baudrillard predicted it might, it’s mostly as propaganda. Contemporary artists and art institutions form a propaganda apparatus that aids neoliberal capitalism in its quest to reinvent itself for compatibility with “wokeness” and intersectionality. There is an insidious goal behind the state ideology’s recuperation of intersectionality: confusion and the narrowing of imagination. If the alleged dissent of the state is dedicating its organizing activities to diversifying the institutions of the state apparatus, what’s going to be the result? What has proven to be the result is that bourgeois state institutions are hardened. They become harder to oppose because opposition to the diversified state is then treated as opposition to diversity itself. The art world, diversified or not, is a bourgeois state institution, and has a vested interest in materializing this illusion. Well, I oppose the state, and I oppose the art world’s role within the state. And I have long ceased caring how people try to smear my position. But unfortunately, most people have not been able to embrace that freedom. Not yet, anyways.

Culture war is merely the illusion of politics - what remains when hope for real change has bottomed out. Culture war is the politics of emotion and theater, built atop paranoid and diminutive understandings of the world. Remember a few years ago when everyone was hopeful that the era of Trump would usher in a new and vibrant movement of political art? I think this could have been true if our artists sought to engage with the political economic decay that led to the Trump presidency in any meaningful way. Instead, we got four years of hysterical anti-Trump art that did little more than ridicule Donald Trump as a figure. It often implicated his supporters in the satire – calling them Nazis and fascists, and such – and often felt like it was more of an expression of the dismissal of the legitimate concerns of poor and working people than it was an honest opposition to Trump’s governance. Trump’s presidency largely applied a vulgar affect to the same neoliberal policies of his predecessors (and on some issues, namely foreign policy, he was infinitely less damaging than them). Anti-Trump art looks more like bourgeois privilege art than it does anything resembling radical political art. And most toxically, anti-Trump art only served to legitimize the forty years of neoliberal political decay that had preceded it. What an embarrassing missed opportunity. Contemporary art is full of sweet little lies with vast implications.

We are now seeing artists associated with the left siding with any and all institutions that are “anti-Trump,” even if those same institutions are more responsible for our rampant inequality than Trump is. Think of feminist poet Eileen Myles – still cloaked in an image of radical politics from her days reading at the St. Marks Poetry Project and their 1992 write-in campaign for president – demanding that Buzzfeed readers support Hilary Clinton for President in 2016 (they supported Elizabeth Warren this year, unsurprisingly) [6]. Myles’ politics have always been rooted in reductive bourgeois identitarianism and lacked substantive class analysis. And now, their role as a radical feminist artist is most useful to a capitalist system that has proven itself more than happy to “diversify” itself at the expense of facing anything resembling organic dissent. Myles, still branded as a freedom fighter, is functionally little more than a branding strategist for the Democratic Party and its tangled web of corporate infrastructure. But it’s that “freedom fighter” brand that provides the useful mystification for useful hegemony. If Myles’ readers – many of whom fancy themselves political radicals, I’m sure of it – get permission from the “radical” poet to support the bloodthirsty war monger, then supporting the bloodthirsty war monger must be the right thing to do. But lesser evilism isn’t virtuous. It is the malicious mantra that legitimizes the soft brutality of the bourgeois state. I don’t want Hilary Clinton as my leader “when the world ends.” I don’t want Hilary Clinton as my leader. She is a repugnant agent of the war machine and stating anything less would be a lie. Myles is a liar.

Is there a leftwing bias in the art world? That depends upon whether or not you view “wokeness” as a leftwing political ideology. Considering what the left has been reduced to, I suppose it is. But it’s certainly not an ideology dedicated to the opposition of capitalism, nor is it one rooted in a Marxist political economic critique. Wokeness is merely the left side of the culture wars, and even more toxically, the left side of capitalism (as Angela Nagle has observed, Silicon Valley has exuberantly adopted the language of intersectionality into its corporate structures [5]). In many ways, wokeness is a hybrid of both intersectional theory and a slightly updated version of the pervasive ideology that Mark Fisher called “capitalist realism,” in that its proponents have ceased imagining a world beyond capital, and have settled for the illusion that something resembling equality can be attained under the current system of liberal capitalism. Instead of rigorous critique of the decay of late capitalism, most artists have chosen to frame their protests around the moral failings of individual actors within the system (Trump, Boris Johnson, whoever). In doing so, they tacitly accept and support the system that these political actors are embedded within, legitimizing neoliberal hegemony, and dismiss the legitimate concerns of working class people who turned to those individual actors for help. Imagine looking a poor person from Michigan in the face whose job has been shipped overseas due to the Clinton-supported NAFTA, seen their communities bottomed out by austerity and stuffed to the gills with pharmaceutical opiates, and calling that person a “fascist” for not wanting to vote Democrat. But this is the message that the art world puts out. According to the art world, this is the signaling of “virtue.”

The art world is the largest market of unregulated goods in the world, so it shouldn’t surprise that it has internalized the version of left politics that doesn’t criticize the political economy of its own function within the system (same as corporate America has). What’s more disquieting is the tendency of contemporary artists to not just remain uncritical towards this phenomenon, but to accentuate its propagandistic narratives in their work and from their platforms. And even artists that I know see through the grift – artists who are smart enough to know that discourse policing and ideological orthodoxy this rigid is never in service of marginalized people (but always in service to those with power) – are tragically afraid to speak out against the phenomena.

Since the 1993 Whitney Biennial, identity politics (or intersectionality), has been the only lens through which realpolitik is analyzed or commented on in the culture industry. Writing about the protest against Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, Walter Benn Michaels writes, “[the protests] represent a variation on a familiar theme, the demand for racial justice as a demand for equality of access to elite institutions,”[6]. This is a nifty trick of the elite, in which an ideology branded as the politics of liberation is ultimately the politics of, at best, a slightly diversified bourgeoisie. There’s a reason that Jeff Bezos votes Democrat and supports Black Lives Matter. Class consciousness is a threat to the system at its basis. Identitarian diversity politics are not.

“Late capitalism” is often misunderstood to be the end point of capitalism, but it actually describes the process of capitalism subsuming social relations that previously remained outside the economic system: community, activism, creativity, certainly identity, and otherwise all become little more than new commodities. If Rachel Dolezal taught us anything (and more recently, Jessica Krug), it is that a “marginal identity” can be used as a method of accruing social capital in our society. Cultural theorist Steven Shaviro defines this process as a “real subsumption” replacing the older “formal subsumption” (the subsuming of surplus value from labor in early capitalism) of early industrialist capitalist relations. “Affects and feelings, linguistic abilities, modes of cooperation, forms of know-how and of explicit knowledge, expressions of desire: all these are appropriated and turned into sources of surplus value,” writes Shaviro. This could explain why so much of what appears to be the work of activism in the art world (exhibitions focused on representation, discussions of queer theory, you get the picture) are little more than expressions of branding and “clout” building at best, and flagrant pieces of mind numbing propaganda at worst. It’s all a moral bludgeoning. I recently saw someone on Instagram saying that what makes Black Lives Matter so excellent is that “it can’t be argued with.” But this is in fact not good at all, it’s reactionary. Because now, you can’t even challenge the financial structure of Black Lives Matter as an organization - and the billons of dollars it collects that seemingly vanishes without a trace - without being accused of believing that “black lives don’t matter.” This is incredibly dangerous, and it’s hard to approach these subjects at all without feeling conspiratorial. And that too, of course, is by design.

Consider the countless “Get out the Vote” fundraisers being held by art institutions on behalf of the Biden 2020 campaign. David Zwirner’s “Artists for Biden” fundraiser, for example, includes works by artists like Jeff Koons, Carmen Herrera, and Kehinde Wiley. What does the Biden campaign represent that necessitates artists use their work to support his candidacy? How is there not a mass cognitive dissonance around these phenomena? The same artists, curators, and institutional figures that take to social media to rail against police brutality, are now raising money for the scumbag politician that wrote the 1994 crime bill, and another who spent her time as a District Attorney incarcerating poor parents for their children’s school truancy. Is Trump really so dangerous that these self-proclaimed left-leaning artists would forgo all the issues they claim to care about? As embarrassed as these people must be to have a reality TV star as president (and that’s really what this is, Trump is an offense to their bougie sensibilities), a reality TV star has probably done a lot less damage throughout his life than career politicians of the federal government. The contradictions and inconsistencies within art world politics are irreconcilable and schizophrenic. Don’t you feel exhausted?

To be “woke” isn’t to have any substantial criticism of our mode of production or the economic basis of society, it is to demand that capitalism wear the mask of “social justice.” And social justice, ever the convenient abstraction, is a goal post that is constantly shifting, because it is market driven. It is fundamentally Keynesian, an argument in favor of guaranteeing some vague idea of personal freedom and liberty within the constraints set by a capitalist political economy itself, which is fundamentally incapable of guaranteeing those personal freedoms to the masses. The broadcasters of major media networks like Don Lemon or Chris Hayes speak in rhetorical tones not too far out of phase with the language of woke academia. Gender and critical race theory have been embedded into the mainstream. And yet, there is more poverty in America now than at any other point in history. We could conclude then that artists don’t actually care about political economic progress, but about yielding a left liberal monoculture in which they are at the top of the chain of social capital. What’s good for them is, in this case, not good for us. Thus, the most extreme ends of the woke ideologies are less radical than they are radically liberal. And a radical liberal, a “radlib,” is fundamentally reactionary. Their politics will almost certainly result in more stripping of rights than in guaranteeing them. They will assist in eroding our civil liberties to free expression and debate. And thus artists, some of our loudest radlibs, are reactionary foot soldiers of the bourgeoisie.

Speaking of reactionary foot soldiers of the bourgeoise: Paul B. Preciado, the liberal art world elite’s favorite “leftist” gender theorist, sincerely asked in a recent ArtForum article if the “revolution” had started with the first #metoo post on Twitter. We can thank Preciado for saying the quiet part loud: “revolution” to art world figures is a revolution of representation. It is at best a bourgeois culture war that won’t make a bit of difference in the lives of those who need help the most. I am convinced that if a real proletarian revolution ever did formulate itself, it would be leftist thinkers like Preciado who would be out in full force smearing the revolution as reactionary or “inconsiderate” to the needs of people of color and women. But this is a revolution all right. It is a revolution of the left side of capital. Under David Velasco as editor, it seems like ArtForum publishes Preciado’s bougie drivel on a monthly basis. Bordiga once wrote that activists like Preciado were the “cancer of the worker’s movement”: “Activism always claims to possess the correct understanding of the circumstances of political struggle, and that it is “equal to the situation”, but it is incapable of engaging in a realistic evaluation of the relations of force, enormously exaggerating the possibilities of the subjective factors of the class struggle.” But tragically, the bougie opportunist activists have won. The worker’s movement is nonexistent. All that remains of left politics is bourgeois activist NGOs. And now that they’ve destroyed all semblances of radical politics, they are infiltrating the arts. They are infecting the last remaining space for open debate and free exchange of often troubling and dangerous ideas with their cancerous venom. The activists have come to abolish art, and they’re succeeding.

30 years of identitarian diversity politics in the art world hasn’t just resulted in a complication of the role of art in our culture, it has tremendously diminished the quality of art being produced. An art that legitimizes the power structure doesn’t challenge us to question our reality and search within ourselves for truth, it demands our fealty (“Vote Blue No Matter Who). Art is now praised for its detectable ideological allegiances: the Democratic Party, “marginalized people,” climate activists, and so on. The art that dares to go beyond mere allegiance and attempts to puncture beneath the visage of our system, that casts a critical eye towards all of our institutions (including the ones aforementioned), or even just employs ambiguity to inspire criticality in its viewers, is met with skepticism, if not outright hostility. In 2016, artist Darja Bajagić created a work entitled Bucharest Molly [8] for an exhibition at Galeria Nicodim called Omul Negru in response to its curatorial theme of “aesthetics of evil and paranoia.” The piece – a motion activated fountain adorned with an appropriated image of a woman wearing jeans emblazoned with the words “HEIL HITLER” and a red teddy bear with a swastika on it – was removed from the show by its curators. In this situation, the dynamics I’m describing are well illustrated. Although Bajagić’s work clearly aligned with the show’s theme, it offered no clear moral assessment of its subject matter. It was ambiguous. Thus, the curators of the exhibition weren’t looking for artistic analyses and aestheticization of the signifiers of evil, but rather for the artists to isolate and make judgement of the “evils” most commonly commented on in the art world: racism, white nationalism, “authoritarianism,” and so on. Ambiguity inspires us to think for ourselves and to question beyond the orthodoxies that we’re conditioned to accept, and the art world (as a propaganda arm of the left side of capital) cannot tolerate open-ended thought.

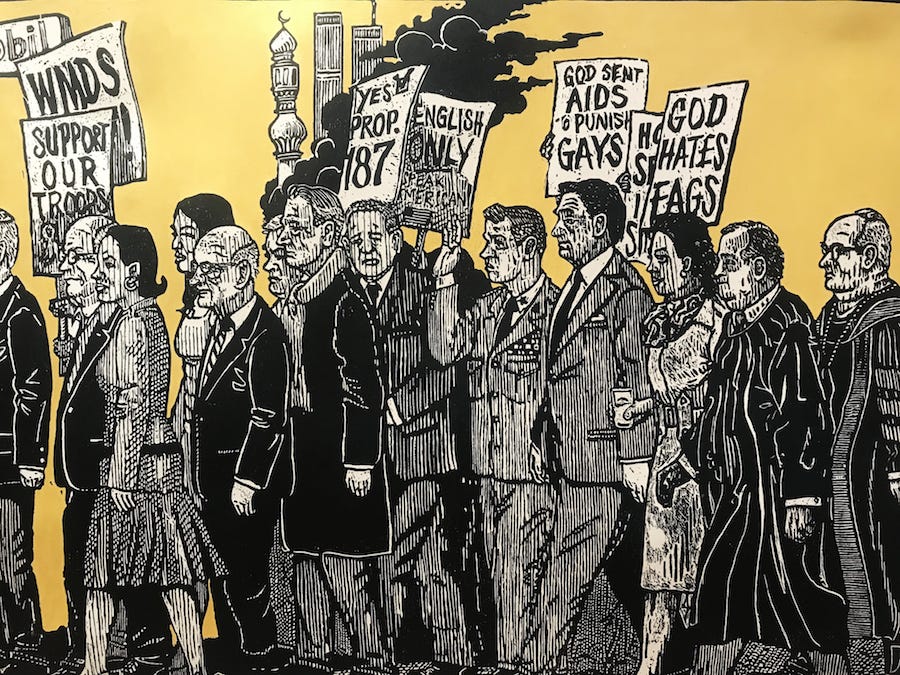

The worst artwork I’ve seen in recent years was Sandow Birk’s piece of flagrant Democratic Party pandering propaganda from his exhibition at PPOW in 2018. Entitled Procession, the work features two woodblock prints placed side by side. “The Left'' depicts everyone from market nihilists like Nancy Pelosi to historical labor socialists and civil rights icons like MLK Jr. “The Right” depicts rightwing figures from vulgar neoliberals like President Trump to the unambiguously evil Ku Klux Klansmen. Birk makes no room for the countless distinctions in political orientations that exist between the figures within each side, seeming to lump everyone into a simplified binary in which they are “left” or “right” or “good” or “evil.” The piece is a disastrous embodiment of the incoherence of identity politics as practiced within the art world: no complexity nor nuance. To see Fred Hampton and Barack Obama as being on the same team is childish and embarrassing. To see Trump and Richard Spencer on the same team is equally childish and embarrassing (note: even more so now that Trump doubled his vote tallies with people of color).

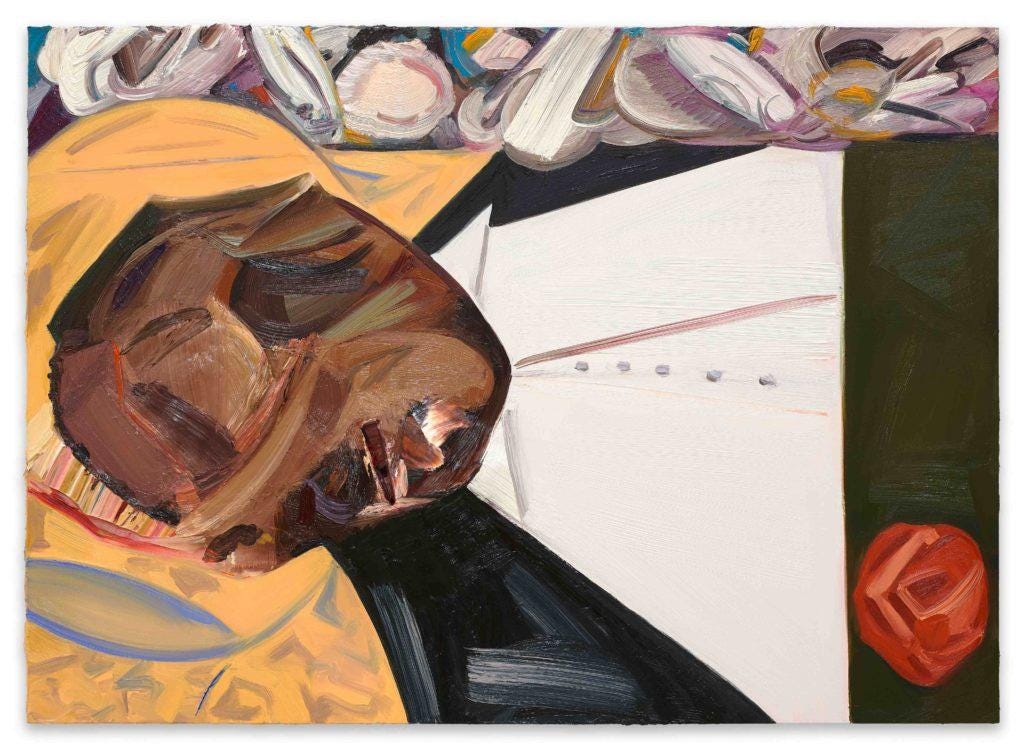

In another example of identitarian limitations in art, Arthur Jafa received much praise for the incorporation of the clip of Obama singing “Amazing Grace” (after the Charleston mass shooting by white supremacist Dylann Roof) into his breakout video montage Love is the Message, The Message is Death. But wouldn’t the video have been that much more powerful if the Obama clip he included was the one in which Obama pretended to drink Flint's poisoned water as a means of dulling the outrage over the water crisis? Wouldn’t the more provocative and true critique be one in which the artist emphasizes the abandonment of the black working class by the black political elite? Jafa, inadvertently or not, reinforced the notion that Obama’s “blackness” should be celebrated, even if the political actions of Obama decimated the working class, black and otherwise. Artists – like Jafa – have largely abandoned their historical roles as distant observers and critics of the societies that they’re embedded in. Instead, they consume, regurgitate and amplify the reductionist narratives of the ruling elite.

Byung-Chul Han demonstrates that in the late-20th and 21st Centuries, capitalism no longer needs to project a brutal and oppressive affect (“Big Brother” or whatever), it can subjugate the citizenry through seduction [8]. This could explain why so many corporations – the most prolific producers of inequality – have easily internalized intersectionality into their branding structure. They are, quite literally, seducing us with the aesthetics of progress to lull us into acceptance of their dominion. Contemporary art has established itself as a striking step in the dance of seduction being performed by neoliberalism before us, its spectators. “Art world left” politics fetishize racial and social justice over class analysis because the art world feeds on the patronage of finance capital, and is a vital component of the broader myth being constructed: that a world without oppression can be created under current political economy. And what we are seeing is that we tend to cling to this complacency. The illusion of progress makes us feel safe, and when cracks appear in that illusion we panic. We need to patch up those cracks, to silence the dissent. Thus, neoliberalism doesn’t require an institutionalized propaganda apparatus enforcing speech and thought from the top down, because its own subjects are more than willing to censor one another to protect the illusion. Our censorship is bottom up. Thus, Censorship in the art world or “cancel culture” – mimicking the logic of neoliberalism more broadly – isn’t being enforced by institutional authorities, but by the social media-fueled collective anger of people embedded within it, and its consumers. By regurgitating the censorship methods of neoliberalism, the art world has become a powerful vindicating tool of bourgeois state ideology.

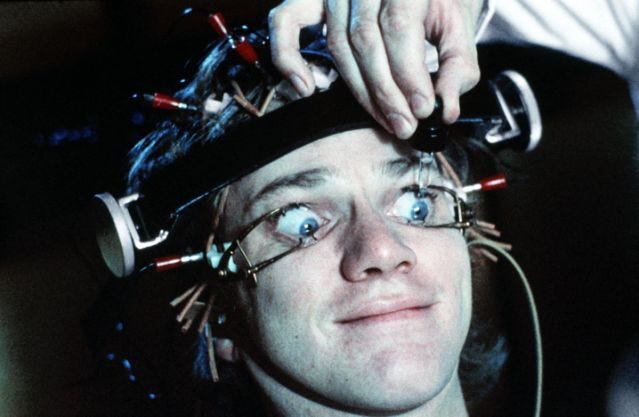

The art school has become a kind of “psychological operation” or “psy-op,” that indoctrinates young artists into identitarian neoliberalism (“wokeness” as it were) and, by extension, “morally purifies” the art world. The inculcation starts early. As the writer DC Miller has observed [9], art schools can be understood as what Louis Althusser called “ideological state apparatuses,” or institutions formally outside the state but in cahoots with it so much as they reproduce state ideology. Think of Malcolm MacDowell’s eye sockets surgically peeled open by a pair of specula in A Clockwork Orange. But instead of being made to watch images of violence and depravity as a method of aversion therapy, he is strapped to that chair and howling with indignant discomfort while confronted with images of various “micro-aggressions” and vague oppressions. Ironically, the art school educates students on the functionings and inequalities produced by market neoliberalism while teaching them to commodify not just their work, but their identities, orientations, and otherwise, thereby proselytizing them into that very identity fetishizing ideology now being used to justify market neoliberalism.

Yale’s MFA program, while laudable and I’m sure genuine in its diversity efforts to a degree, produces countless artists dealing with essentially endless reiterations of the same tired subject matter (identity, representation, etc.) Yale graduate Bajagić, who courageously refuses to bow to art world orthodoxy, opting to create work of vibrant moral complexity, was suggested to go to therapy on school dime by Yale School of the Art’s Dean Robert Storr for the artist’s use of violent and pornographic imagery. The implication here is stunning: if you make different work or think differently than the rest of your class then you must literally be mentally ill. This is the art world enforcing its own ideology in the most direct and brutal manner.

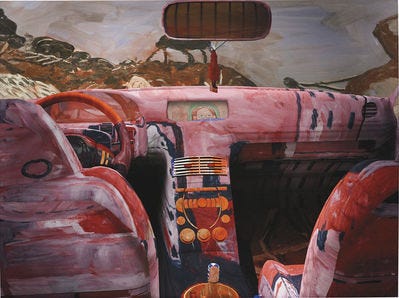

But when the academy fails to entirely brainwash dissent, ideological flexibility and critical thinking out of young artists, socially enforced censorship, or “cancel culture,” is a more than effective method of “othering” if not outright silencing the artists that have managed to uphold the historical role of the artist as challenger of cultural credo. At the risk of sounding conspiratorial, it seems all too perfect that of all the successful artists to be recently smeared with with absurd sex scandals [10] founded upon nothing other than the petty grievances of the accusers pushing the scandal, that it was an artist like Jon Rafman. Rafman’s accusers appeared to be hyper-versed in the art of cancel culture. They were Internet savvy, knowledgeable in the weaponization of market logic, using an Instagram account with aesthetically pleasing graphic design to maximize the visibility and intoxicating fervor of their campaign against the artist. Rafman, who boldly stated to Spike Magazine [11] that, “The totalitarian desire to dissolve the distinction between art and politics is a sign of regression,” challenges woke capitalism’s stranglehold over contemporary art production, and his success could be viewed as a rejection of identitarian orthodoxy in the art world. Call me crazy, call me apophenic, but we are living through schizoid liquid modernism. Nothing is off the table. “Conspirators have a logic and daring beyond our reach,” writes Don DeLillo in Libra [12].

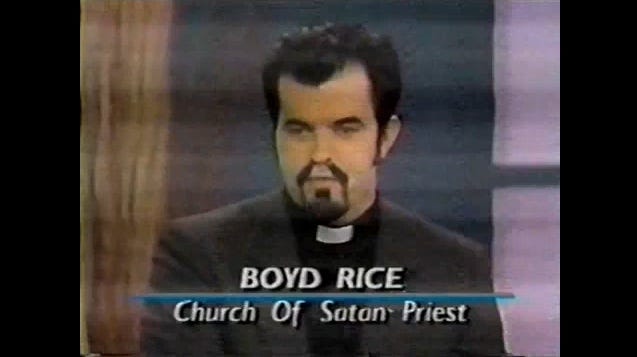

But one needn’t rely on conspiracy theorizing to understand the ways that the art world uses manufactured outrage to police its internal ideological narratives. The aforementioned Bajagić endured peer-driven censorship when she was slated to show her work alongside Boyd Rice, a pioneering industrial musician and artist with a “checkered” ideological history, at Greenspon Gallery in 2018. After the exhibition was announced, an artist listserv known as Invisible Dole led a targeted harassment campaign aimed at the gallery’s owner, Amy Greenspon, accusing the gallerist of showing a “neo-Nazi” artist [13]. While Rice has denied neo-Nazi associations, claiming his practices were part of a larger ethos of transgression, that didn’t stop major, institutionally backed, wealthy artists like Josh Kline and Anicka Yi from flexing their power and making sure that no one but a select few would see this show.

Back in 2017, the London-based L.D. 50, a gallery owned by Lucia Diego that had previously shown work by Jake and Dinos Chapman and other major artists, was forced out of business by an Antifa-led smear and protest campaign. The gallery had hosted talks by the politically idiosyncratic philosopher Nick Land (who founded the CCRU and mentored left-aligned thinkers like Mark Fisher and Kodwo Eshun), the unquestionably rightwing figure Brett Stevens [14], and others of similarly – shall we say – art world atypical ideologies. One of the campaign’s figureheads, Turner, started a Tumblr page entitled Shut Down L.D. 50 to accuse the gallery and a few vocal supporters – the young artists Deanna Havas and Daniel Keller, and the academic DC Miller among them – of “fascism,” “anti-semitism,” Islamophobia and all the various “isms” and “phobias.” Though Turner rarely produced evidence of anti-Semitism beyond the figures previously named making jokes at his personal expense, the protest campaign “SDLD50” insisted on referring to Luke Turner as a “victim” of anti-semitism and homophobia (as if it was his religion being mocked and not his histrionic and childish displays). And though Turner has become something of a private joke amongst artists (Mathieu Malouf named a 2019 exhibition Luke Turner is ReTarded after Turner got Red Scare co-host Anna Khachiyan temporarily banned from Twitter for referring to him using that epithet) (note: I now too have been suspended from twitter for use of the epithet LOL!), his actions have had real material consequence. Miller has had to self-publish his critiques, assumedly without pay. Havas’ promising career was severely railroaded. Even the leftwing philosopher Nina Power has seen herself the target of harassment campaigns due to Turner’s exploits. The art world is less interesting without them (note: the fact that Turner, who has been one of the art world’s generals of cancel culture for years now, has been absolutely radio silent on the revelations of his friend and art partner Shia Labeouf being revealed as a brutal pig, is truly damning).

L.D. 50, Miller and the others never signaled support of the alt-right, but only the desire to understand and dissect its symbols. Much like members of the alt-right then, art world figures like Turner are reactionaries. Alongside the alt-right, they form two sides of one coin, an ouroboros that ensures that the masses continue waging an unwinnable culture war on one another while the elite solidifies its power over society. Culture war fractures the proletariat along cultural lines, preventing broader solidarity. Thus, outrage culture keeps the status quo in-tact by keeping people in the political binary: left or right, Democrat or Republican, or what have you. LD50, however provocatively, was only guilty of facilitating meaningful dialog between people who ordinarily disagree, but might be able to find some political and social overlap through critical engagement. If only the average Antifa activist knew that Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, a fascist, and Louis Aragon, a communist, were best friends, and that this kind of engagement yielded important ideas and discourse. If only they understood that revolutionary ideas only emerge from the polarities of debate. But then again, I don’t think they’d care. They are more committed to their moral purity than to actual societal change. And arguably it was for this reason that the gallery had to be destroyed. Given that most people embedded in the art world (like Turner and many of the anti-LD50 protestors) benefit economically from the status quo, they have a direct material interest in fanning the flames of the culture war.

In an essay on Ernst Lubitsch and political correctness within today’s political left [15], Slavoj Zizek writes, “The apparent dropping of the masks is often the most deceptive. When fully under the power of ideology, we ‘act ourselves’ because this ostensible directness represses that which can be expressed only indirectly.” When artists join the cancel mobs, they attempt to show us their commitments to justice. But in doing so, they reveal the truth: they are just as intolerant of dissent and contrarian thought as society’s oppressors. Tragically, it appears that their solidarity is with those oppressors. As artists have embraced their positions as propagandists for the progressive side of capital, we’ve lost the sense of the artist as the watchful observer. The outsider. The transgressor of norms. In Against Nature, Huysmans writes, “This idiotic sentimentality combined with ruthless commercialism clearly represented the dominant spirit of the age.” [16] This notion couldn’t be truer now. Artists, precarious and in need of institutional approval, dull their work with empty reiterations of the dominant narratives of progressive capitalism. Where is the complexity? Where is the mystery? Where is the recognition that only in facing the ugliness of the world that we bring about beauty? I am exhausted by the cowardice. Cowardice is the spiritual plague of our time.

Could there might be an opposition forming? “Cancellation” is, from one perspective, a kind of freedom. It frees the artist from the expectations of the conformist spectators. Once cancelled, you are unburdened of meeting the expectations placed upon you by the woke masses, and can then truly critique and comment upon the world around you. There’s a reason that some of the best cultural commentary is happening on podcasts like Contain or The Perfume Nationalist; since these shows are unaffiliated to any institutionalized left (or right) authority, there are no limits to what they are “allowed” to critique. Projects like Mónica Belévan’s Covidian Aesthetics and this one are attempting to elevate the dissident of the internet’s dark subcultural corners to a more visible level of cultural discourse, and there is potential in this. As the spectral moral fatigue haunting the art world slowly materializes at the center of the discourse, cancelled artists will be treated as authorities on the underpinnings of these dynamics. I believe a new criticality will emerge, with artists from across the political spectrum – united in cancellation – dedicated to exposing the contradictions within the woke ideology of the art world: Rafman, Bajagić, Havas, Keller, Malouf, and others. These artists offer hope for a heterodox art, and a creative stance that can meaningfully challenge hegemonic ideological thinking.

Images (in order) Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, art by Gunter Brus, Baudrillard, evil of Hilary, ‘Open Casket’ by Dana Schutz, Biden campaign, art by Darja Bajagić, art by Sandow Birk, Byung-Chul Han, art by Jon Rafman, art by Deanna Havas, Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, Boyd Rice

CITATIONS

[1] Ian Brady, The Gates of Janus: Serial Killing and its Analysis by the Moors Murderer Ian Brady (Feral House, 2001).

[2] Francis Stonor Saunders, “Modern Art was CIA ‘weapon,’” Independent (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/modern-art-was-cia-weapon-1578808.html), October 1995.

[3] Jean Baudrillard, “The Conspiracy of Art,” The Conspiracy of Art (Semiotext(e), 2005).

[4] Maya Rhodan, “‘A Game Changer!’ How a Painting of President Obama Broke the Rules,’ Time (https://time.com/5158961/obama-portrait-kehinde-wiley-amy-sherald-interview/), February 2018

[5] Angela Nagle “How Big Business Came to Love Sounding Progressive While Protecting Status and Privilege,” Current Affairs https://www.currentaffairs.org/2017/11/silicon-intersectionality, November 2017

[6] Walter Benn Michaels, “Who Gets Ownership of Pain and Victimhood,” le Monde diplomatique https://mondediplo.com/2018/05/14race-class, May 2018

[7] Eileen Myles, “Hilary Clinton: The Leader You Want When the World Ends,” Buzfeed News https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/eileenmyles/hillary-clinton-the-leader-you-want-when-the-world-ends, February 2016

[8] Byung Chul-Han, Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, (Verso, 2017)

[9] DC Miller, “Against Political Art,” re-published to Miller’s Medium https://medium.com/@dctvbot/against-political-art-db34ff7dfac3, May 2014

[10] Sarah Bahr, “Hirshhorn Suspends Jon Rafman Show After Allegations of Sexual Assault,” New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/28/arts/design/hirshhorn-museum-jon-rafman.html, July 2020

[11] Aaron Moulton, “Portrait: Jon Rafman,” Spike https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/articles/portrait-jon-rafman, March 2020

[12] Don DeLillo, Libra (Viking Press, 1988)

[13] Alex Greenberger, “Greenspon Gallery Cancels Show With Artist Boyd Rice, Alleged neo-Nazi,” Art News https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/greenspon-gallery-cancels-show-artist-boyd-rice-alleged-neo-nazi-10931/, September 2018

[14] May Bulman, “‘Far-right’ Gallery in London Forced to Close Because it Keeps Getting Attacked,” Independent https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/far-right-gallery-art-hackney-ld50-london-attacked-shut-down-lucia-diego-nick-land-andrew-osborne-a7631971.html, March 2017

[15] Slavoj Zizek, “Ernst Lubitsch, Censorship, and Political Correctness,” American Affairs Journal https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2018/08/ernst-lubitsch-censorship-and-political-correctness/, (Fall 2018)

[16] Joris-Karl Huysmans, À rebours (Charpentier, 1884)