Like the greatest mystery stories, the pseudonymous writer Ivan Boris’ excellent new novel, My Week Without Gérard, is a labyrinth without a center. There is nothing to unravel here. There is no secret knowledge to be unearthed. No, instead, the mystery’s essential unknowability IS its only revelation; its ineffable enigma, its fluid arrangements of scenarios, characters, and even timelines, is its mesmeric allure. And not unlike other mystery or detective novels that similarly experiment with form and generic style, My Week Without Gérard demonstrates a stunning clarity about the culture and political economy that it was written in. The empty mystery that holds the novel together, is the same mystery that perplexes us all in liquid modernity. None of it makes sense. None of it seems real. If so much is happening, then why are we in stasis? While it skirts neatly tied up narrative implications, there is a profound – even disturbing, perhaps – philosophical insight here,

Similarly to Thomas Pynchon in Inherent Vice, Boris utilizes the generic structure of detective pulp fiction as raw material that he can deconstruct, fragment, and imbue with a freewheeling experimental sensibility. Inherent Vice has been written off by some critics as Pynchon’s detour into light reading, and that criticism isn’t exactly false. But Pynchon also managed to subvert the well-worn genre tropes of the detective novel in a way that materialized his pseudo-philosophical cultural critiques more legibly than any of his masterpieces had prior: paranoia, conspiracy, social change, drugs, and more. Boris employs the structure to similar ends, and the mystery “plot” becomes a thread that he uses to tie together a hallucinatory and temporally fractured literary space. The novel is hilarious at times, and transgressive throughout. But unquestionably its greatest strength is in its conception of the world we live, or at least, the phantasmagoric simulation of a world that we live in. And the anxiety we feel in it. And the desire we have to escape it.

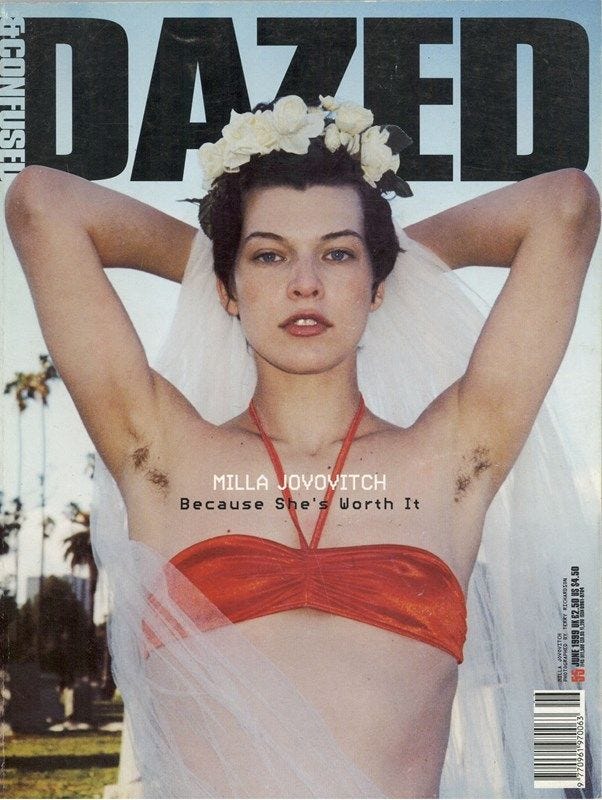

The novel follows an ambitious and unusually art historically sophisticated – if generically narcissistic and drug-numbed – journalist named Lester Langway, who works for a failing, formerly hip style magazine (similar to Dazed or The Face). Lester heads to Paris to locate a Foucaut-level famous philosopher named Gérard Derenne, who has gone missing. Lester encounters problems in his search for the philosopher almost immediately. First, it appears that his editor from Down N’ Out! magazine has no recollection of assigning Lester the project, and has ceded control of his publication to his authoritarian, clout chasing assistant. His interview with fellow philosopher and Derenne’s best friend “Jacques Dutronc” (cleverly named after the French pop star of the same name, emphasizing the fluidity between intellectual life and fame in post-digital capitalism) goes disastrously. And finally, Lester finds himself at the center of a Me Too! Scandal when a female associate of Derenne’s goes to the press and describes the prank phone calls that Lester has been sending her way as “abuse,” and – in a brilliant satire of the cowardice displayed by bourgeois creative institutions’ failures to protect their artists from unfair smears (Jon Rafman, anyone?) – Lester’s union doesn’t even attempt to protect him from the character assassination or the media distortions around the accusations. All through this, there is a femme fatale of sorts, Anaïs, who signs on to Lester’s project as his photographer, and the two embark on a very bizarre, but rather erotic, romantic journey together, that keeps the deeply bizarre story grounded in mercifully familiar images.

The more calamities that befall Lester throughout the story, is the further that Boris drags us down into an abyss of surrealism, temporal slippages, and the depths of a drug and literature-soaked mind. At a certain point, the book becomes less of a tale of mystery and investigation and more of a psychedelic and opioid-spiked fever dream residing within the subconscious of the artist who feels like he was born in the wrong era. The second half of the novel is to the first what Twin Peaks: The Return was to Twin Peaks: the warped, mirror-image phantasmagoria of it. It becomes a poem of nostalgia, and a mourning for the radical avant-garde of early modernism that has further collapsed in the 21st Century.

My Week Without Gérard is a French modernism bibliophile’s wet dream. Throughout, there are bountiful references to Bréton and other surrealists like Artaud and Bataille (both of whom were eventually ousted from the group, but whatever). The Bureau of Surrealist Research, which was historically opened by Artaud in 1924, is reimagined as a kind of museum, or is possibly still in existence somehow (in the context of the novel), as an echo of time, or a murmur of Lester’s vivid imagination (but more on that later); it appears throughout the novel that in this Bureau of Surrealist Research, a Pandora’s Box is waiting for Lester to come and open it. The Bureau becomes centered as the portal between our world, strange as it already is, and the one that Lester enters, which seems to follow a slippery logic similar to the Polish town depicted in Bruno Schulz’s The Streets of Crocodiles. A fog of uncanny emerges from the Bureau that renders all the events and locations that follow it strange… There are references to psychologists, from R.D. Laing to Jung to Wilhelm Reich. And then, there’s the magic. The occult. Colin Wilson’s The Occult. Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Psychomagic. Peter Haining’s The Necromancers. The literary references allude to a rich interiority attempting to escape outwards. The mind. The imagination. Magic. And that’s where Boris forces us to ask: “What is really happening here?” Is this an occult voyage into the heart of a mysticism-saturated, modernism-haunted Paris? Or is it the psychological landscape of an alienated, drugged out, tragically nostalgic, and literature obsessed psyche? The joyful psychosis of the novel is in making no such distinctions between these two notions of its content. Just accept its unlogic. “In the 21st Century, a schizoid personality can be an asset,” says Lester to Anaïs at one point in the novel. Too true. In fact, it might not just be an asset, but a necessity, suggests Ivan.

There is a deliriously reactionary sensibility that courses through the novel. Lester longs for the poets and writers of Surrealism and of early modernism. He drifts through a Paris that only exists in the recesses of his imagination, a Paris that he has embedded into his interiority through his reading and made his inner world. I identify with Lester’s condition. He’s out of time. He wants to be a kind of artist that simply isn’t allowed to exist anymore. He missed modernism by decades, and even the cheap postmodern imitation of it found in “radical” British style magazines is on its last legs. He came in at the end of art’s dilution and just before there was no more art to dilute at all, just “visual culture” to dispose of and ignore. Where do you go from there? He has no choice but to retreat inward. This is, quite often, a book about the collapse of art itself. Boris unearths black comedy in the digital graveyard of post-postmodern art and literature. Derenne in the novel is a philosopher, sure, but he’s even more so a celebrity and a vulgar, neoliberal elite. Boris suggests that the only artists that are gifted with any kind of cultural presence or platform are those that metaphorically (or physically) fellate the encrypted forces of power that dominate beneath the shadows of conspiracy.

In one of the most unforgettable sequences of the novel, there is a peculiar tragedy in Lester’s attempt to hex three unnamed conspirators that have plagued his project and his quest (Derenne, perhaps? Dutronc?). In a nothing short of ecstatically fucked up sequence, Lester performs an erotic blood rite with Anaïs and an occult knowledgeable supervisor, who guides the couple through the process. “Lester entered Anaïs smoothly and held himself inside her, blood squelching,” writes Boris. “Mike lay his hands on her head and instructed her to suck the light from Lester. Lodged inside her with his eyes closed, it took a great deal of Will to keep from releasing his power. ‘I’m going to cum,’ he said more than once.”

And yet, despite all that “power” flowing through Lester, the ritual gets him no closer to his goal, no closer to Derenne, and no closer to understanding the world or rationalizing his own place within it. But Lester isn’t just lost in his own interiority. His fantasies of early modernism aren’t even built on anything resembling historical reality. At a later point in the novel, for instance, time starts to collapse and come undone. Worried about Anaïs’ psychological state after the ritual and a bad psilocybin trip, Lester brings her to a mental health facility, that we learn is Wilhelm Reich’s Orgone Institute. Lester’s encounter with the famed psychoanalyst and Marxist “free love” theorist is presented as neutral, as if Wilhelm is exactly where he ought to be; like it’s not strange at all that a man who died decades ago is taking patients into his hospital in the 2010s. And while Lester is excited to meet him at first (who wouldn’t be?), Reich quickly reveals himself as a quack doctor who imparts his untested theories onto vulnerable patients, sometimes irreparably fucking them up. It turns out that the radical ideas that make The Orgone Energy Accumulator, Its Scientific and Medical Use such wonderfully weird reading are also what make him functionally terrible as an actual physician. So not only does Lester long for something that has already long since passed, he longs for something that maybe never was. His contempt for his own epoch has made him uncritical towards the history that he has imbued with a near supernatural importance. He’s so alienated from his own reality that he has to imbue his own aesthetic and ideological biases onto a former era that he fetishizes. Is that not the very definition of reactionary?

But Lester is, nevertheless, empathetic, and his reactionary tendencies are presented as perfectly logical in the context of the novel. Does Lester eventually find Derenne? He sure does, but it’s so besides the point by the end of the novel that it feels like it barely happens at all. Lester gives new meaning to the term “unreliable narrator,” because he is too lost within his own fascinations, perversions and fantasies to give an accurate account of anything. But given the world he lives in – cancel culture, shadowy elites, the collapse of meaning, a decadent empire in steep decline, abject cynicism masquerading as coherent politics – can we blame him?

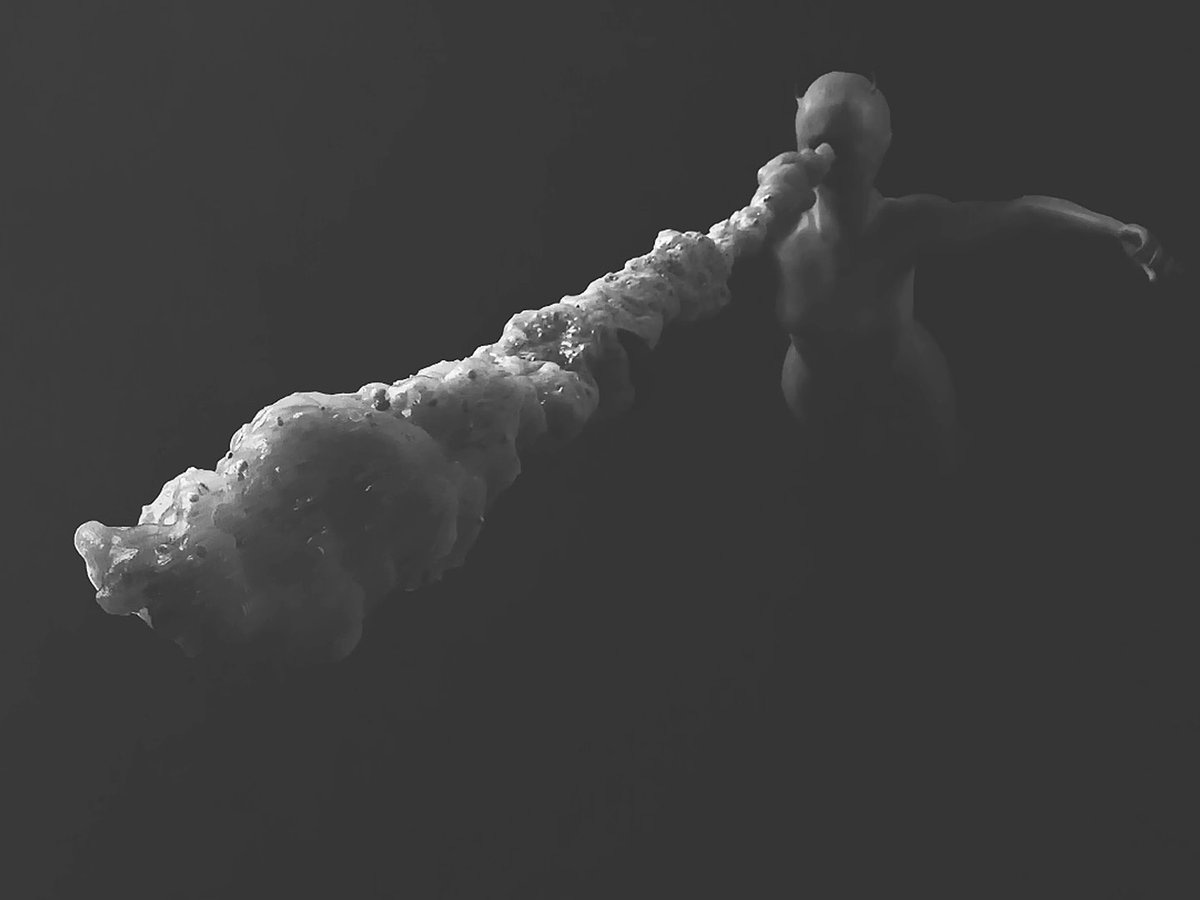

Lester presents himself as something of a surrealist journalist, or at least that is his goal at the beginning of the novel, and the world no longer has any tolerance for an artist with that kind of ambition. The only publisher that will work with him is a failing style bible, and even they are losing patience with the ideas that he brings to the table (“We don’t do philosophy!” says his editor, at one point). Humorously, Rick Owens is depicted throughout the novel as a pillar to the kind of artist that Lester on some level wishes he knew how to be. Owens – a fashion designer with a ruthlessly specific viewpoint, a sculptor of brutal forms with a seemingly limitless imagination – simultaneously embodies the unhinged creative id of an earlier modernism while also still maintaining a massive cultural presence and the material riches that fame coincides with in post-digital neoliberalism. Rick is both a “sexual personae,” and a pop media superstar. To maintain that level of artistic integrity AND world wide recognizability is nothing short of astonishing. Rick Owens is an artist that belongs in the here and now. Lester doesn’t. Lester envies him. I envy him. I am Lester Langway, and like Lester, I retreat into my interiority to escape the alienation that subsumes me. Like Lester, I would rather waste away forever in my own “Library of Babel'' than slowly go insane in the schizoid landscape of a broken culture that no longer places any value on creativity, iconoclasm, or freedom. The world within. The world I’ve built. The material world around me is just too cold, and too ugly.

My Week Without Gérard is available from Morbid Books for presale now, and it will start shipping on March 20