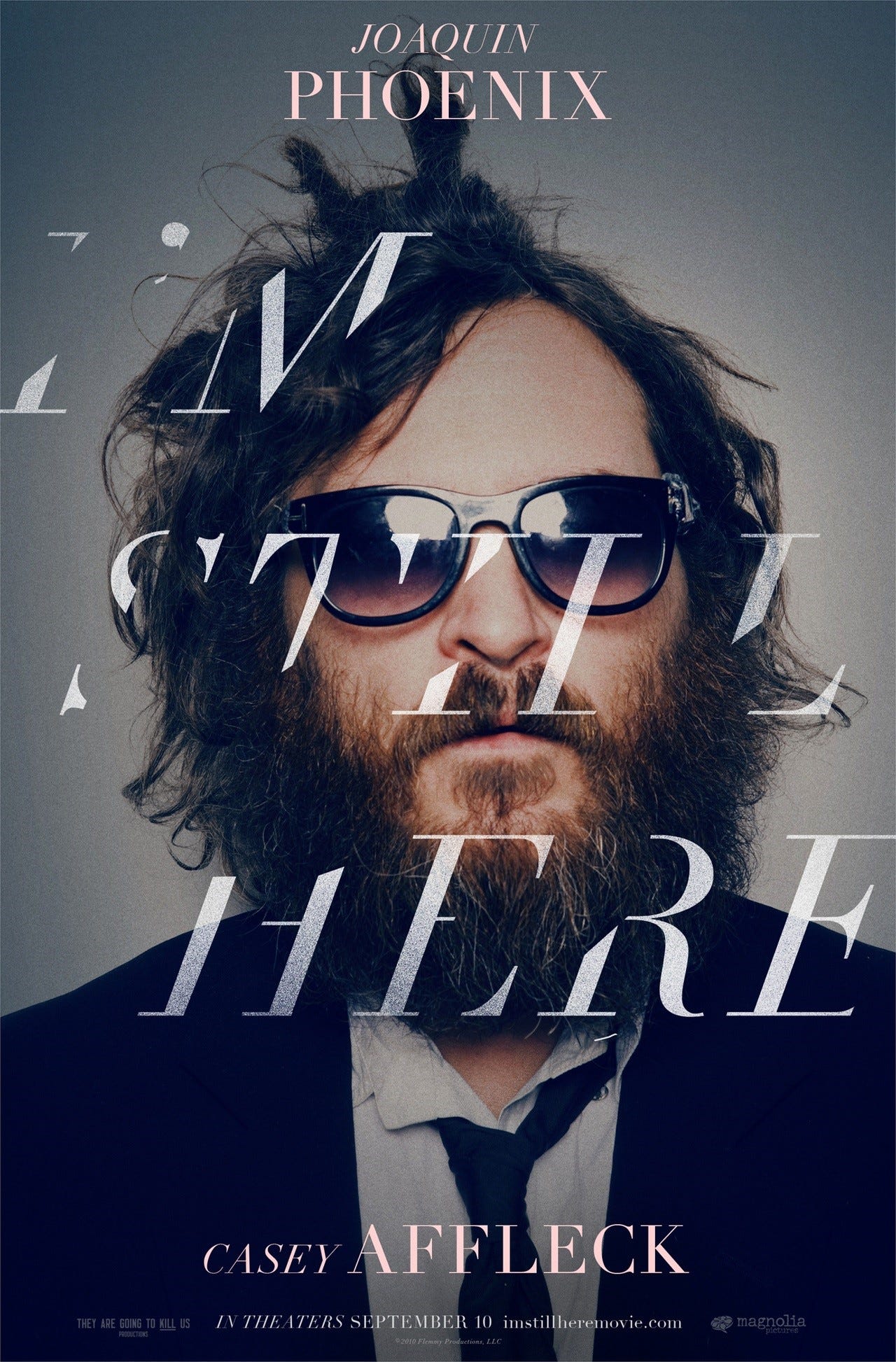

Instances of Crypto-Transgression #6: I'm Still Here, by Adam Lehrer

How the Joaquin Phoenix breakdown mockumentary predicted the 2010s and the rise of Donald Trump, more

Perhaps a testament to the temporally flattening effect that the internet has had on the forward momentum of history, the “mental breakdown” of Joaquin Phoenix feels like it was simultaneously just yesterday AND a million years ago. The actor grew a mangy beard and ballooned in weight. He appeared in public mumbling and incoherent, leading most to believe that the hard drugs that took down his brother River were now wreaking their havoc upon him as well. Most publicly, he went on Letterman to promote the (not bad) James Gray movie Two Lovers and absolutely bombed, failing to answer any of Letterman’s questions, babbling, and infamously sticking a piece of chewed gum beneath Letterman’s coffee table, all for a live audience. All this strange behavior actually transpired over the course of 2008 and 2009 and — as we found out later — was almost entirely staged. Joaquin was performing. He was acting the part of the self-sabotaging celebrity. He was elaborately trolling the public and, more importantly, the smug media, before the concept of trolling had taken center stage in the discourse.

All of this was revealed when the mockumentary I’m Still Here, directed by Joaquin’s now ex-brother-in-law Casey Affeck, which documents the majority of this strange bit of thespian performance art. I re-watched I’m still Here last week at the Roxy, where it was being screened as part of a series curated by filmmaker Michael Bilandic called “Wankstaz” (I’m going to blame the Roxy for not using the much more obvious series title of WIGGERZ) that looks at films depicting white people engaging with hip-hop culture. Nevertheless, I was shocked at how prescient and, in hindsight, almost philosophical I’m Still Here remains over 10 years after its release. Watching this film for what must have been at least the fifth time, I’m Still Here plays like an abstract prophecy of the 2010s – if the medium is indeed the message, then the hoax is indeed the reality.

I’m Still Here captures what appears to be Joaquin’s steep decline into egomaniacal and narcissistic madness as he “quits” acting and embarks on a career in “rap music”. In the scenes that capture Joaquin in private settings — his house in Los Angeles or his apartment in New York or various hotel rooms around the country — he abuses and humiliates his friends and assistants (such as Anthony Langdon, guitar player of the middling rock band Spacehog and the unknown actor Larry McHale) to an extreme degree, culminating in a scene in which Joaquin apparently catches Langdon in the act of selling his private info to press and telling his friend:

“You’re nothing, I SHIT ON YOUR FACE!”

Langdon infamously responds by waiting for Joaquin to fall asleep, so he can actually shit on his face. Which he “does” (they used wet coffee grounds.)

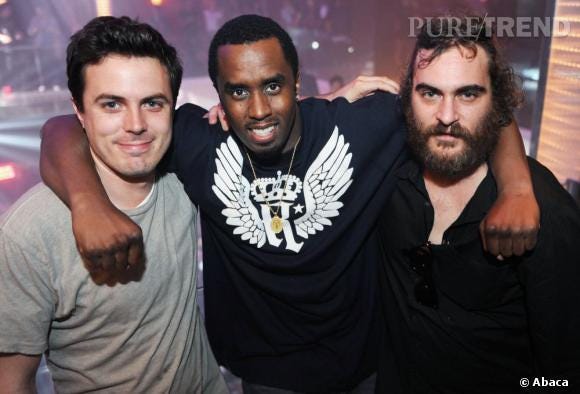

But these scenes, of course, were all scripted and acted. In all likeliness, the actors involved were all having great fun while doing so. What is less clear is the extent to which the famous figures outside of Joaquin’s tight-knit crew of Affleck, Langdon and McHale knew what was going on. OK, so it’s pretty fucking obvious that P. Diddy, who Joaquin pursues throughout the film in “hopes” that the music mogul might produce his debut rap album, was very in on the joke – his comic timing is just too perfect for him not to have been (“You wanna get with me you better bring me some money,” says Diddy. “I have money,” says Joaquin. “How much you got?” asks Diddy, eyebrows raised).

So Diddy knew what was going on, but did Jack Nicholson, Sean Penn, or any of the other stars who Joaquin runs into and behaves utterly bizarrely in front of? Did Ben Stiller? Did Stiller really know that Joaquin was playing the part of Joaquin Phoenix — mentally deteriorating, drug addicted, egomaniac retired actor — when Stiller showed up at his house to offer him the role of Ivan for Noah Baumbach’s Greenberg, only to find Joaquin belligerent, ill-prepared to the point that he thought he was being offered the role of Greenberg himself (which Stiller played), and arrogant enough to insult Stiller’s brand of humor as displayed in There’s Something About Mary.

“A fucking frozen cat?” exclaims Joaquin. “That’s supposed to be funny?”

Joaquin’s friend looks unsure about what his boss is talking about, to which a shocked Stiller says: “It was a dog. He’s talking about There’s Something About Mary.”

There’s one part of the film that I’m almost positive captures Joaquin in a moment of unplanned emotional authenticity. Affleck chooses to make Joaquin’s iconic David Letterman interview the climax of the film’s narrative. After failing to impress Diddy with his rap songs at the Bad Boy Entertainment CEO’s studio, Joaquin chokes back tears (acted) before walking back to his car to furiously inhale a fist full worth of blow. He then immediately calls his publicist and declares that he will, in fact, help promote his new starring role in Two Lovers. Joaquin travels to New York with his cohort, and Affleck captures a palpable anxiety simmering around Joaquin’s team in the lead-up to the interview, as if they all know what is about to transpire and how disastrously wrong it will go. And, as it hardly needs rehashing, it does go wrong indeed.

Just after the interview, I believe that Joaquin’s performance broke for the first time. No matter how deep he was in the artistry of the performance, when he cries in his older, maternal publicist’s arms, I think we’re seeing something real. Because, yes: he was acting. But that doesn’t dull the deep humiliation of realizing that your terrible, asinine behavior will then be broadcasted on loop for months and maybe years to come. In that moment, Joaquin surely worried that he’d gone too far, and that his life and career as he understood it and worked so hard to make it could very well be over. Forever.

So, this begs the question, was self-sabotage on this level worth it for mere art? For the thrill of deception? Probably not, so we have to ponder: why did Joaquin do it?

In the Lettrist International essay “A User’s Guide to Détournement”, Guy Debord and Gil Wolman argued: “Every reasonable person of our time is aware of the obvious fact that art can no longer be justified as a superior activity, or even as a compensatory activity to which one might honorably devote oneself.” What Debord and the Lettrists understood is that in the society of the spectacle, there is no distinguishing between what is pop culture and what is art, it all is subsumed beneath the propagandistic mechanisms of the culture industry. These insights would become truer as modernism died out and postmodernism rose to the surface, as information delivery systems would grow in technological sophistication, and as the 20th Century became the New Millennium – a vulgar singularity would vaporize all culture into one gaseous whole. The opening pages of Bret Easton Ellis’ Glamorama captures these dynamics in an interesting and hilarious manner, with art world figures and tabloid has-beens and prestigious filmmakers all dutifully being added to the guest list for the simpleton handsome protagonist Victor’s club opening. What matters is not what made them famous, but the very fucking fact that they are famous.

It’s very easy to see now that Joaquin was ill at ease with the role that pop culture was casting him in. I’m Still Here is ultimately a meditation on fame in the 21st Century, and Joaquin had undeniably grown weary of his own fame. In the 2000s, Joaquin was considered a “good actor”, but not an extraordinary one nor one who we ever thought would amount to the actor that he eventually became. We liked him in Gladiator. He was a nice presence in some otherwise unwatchable M. Night Shyamalan films. But, the moment he seemed to snap and become antagonistic towards his own role as a rising Hollywood celebrity was with the release of his star-making performance as Johnny Cash in the utterly middling Walk the Line biopic. Joaquin was profoundly alienated by the clichéd narrative of it all – surviving movie star brother of a dead movie star moves through the ranks of supporting performances only to break through with, yes, an Oscar baiting biopic. This was a star who already held contempt for the media after the way his brother River’s overdose was treated by it, and one who saw plain as day how repugnant it all was in the marketing push to make his Johnny Cash depiction an Oscar winner. Leaving aside the fact that Joaquin’s Cash came only a year after Jamie Foxx’s Ray Charles, and followed the exact same publicity script, it was all so pre-packaged, so artistically bereft, and so deeply corporate. He felt in his bones that he didn’t want to live that life.