Edgelord #1: Edgelord vs. Borelord, by Lev Parker

In what will be the first of a series of columns for Safety Propaganda, Morbid Takes, 'Morbid Books' founder Lev Parker explores the importance of the "edgelord" as a resistance of the "borelord"

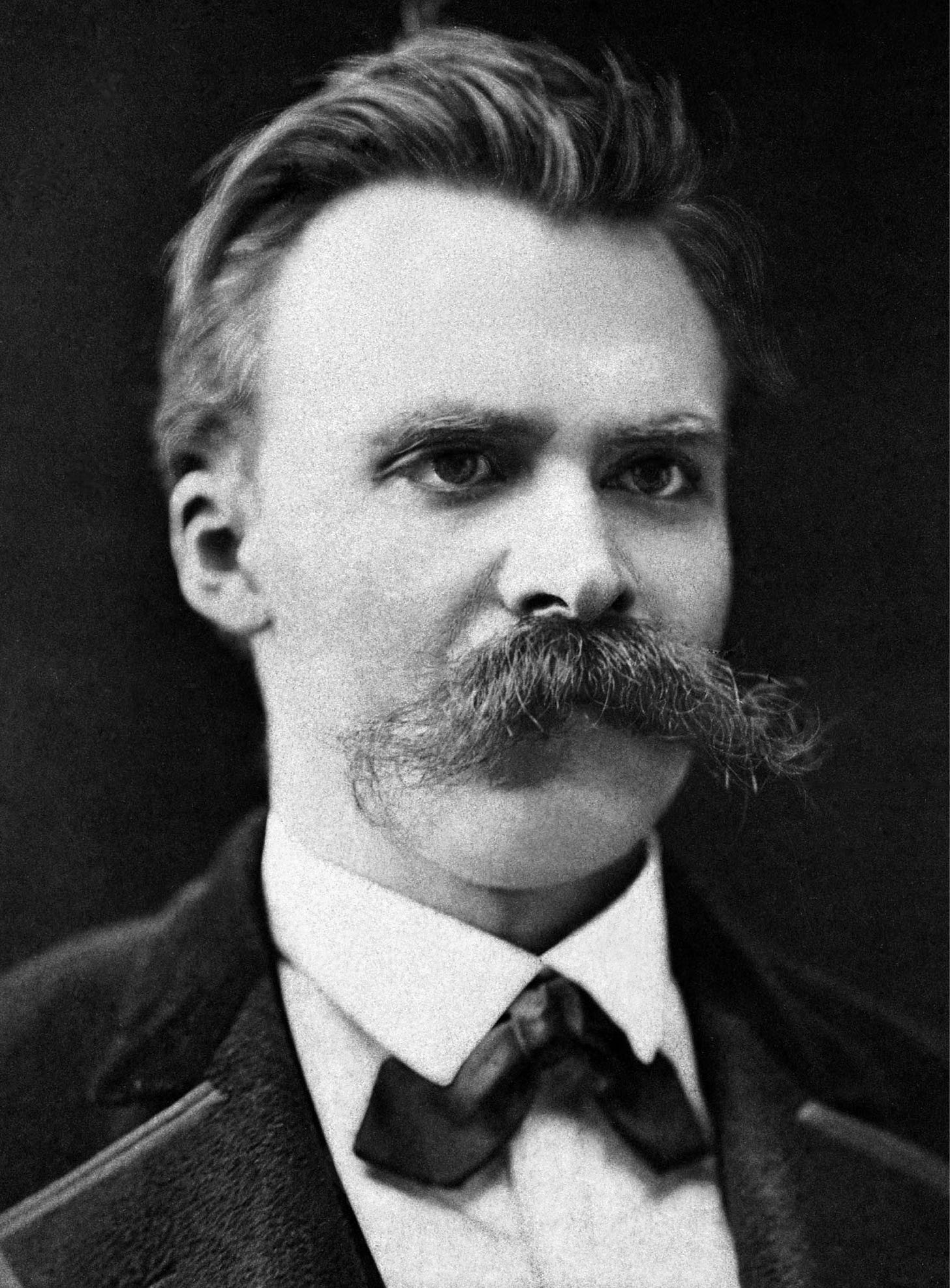

“Edgelord” appeared in the Urban Dictionary in 2015, the year I started publishing Morbid Books. Coincidence? It is a sarcastic honorific, aimed at those who take an intellectual adventure into the darker realms, exploring the nuances or maybe the shock value of taboo ideas and aesthetics. The patron saint of edgelords, Friedrich Nietzsche, said what is new is always regarded as evil. So I take “edgelord” as a compliment, a validation of relevance. As the chairman of the Temple of Surrealism, I thank you.

There are plenty of reasons to be “edgy,” and there have been for longer than the term edgelord has been around. Baudelaire observed that Paris was, at the time of writing, “radiating universal stupidity.” The parallels to today’s internet “cancel culture,” where more serious publishers claim not to understand our prize-winning jokes, are obvious. Baudelaire took a similar glee in riling the righteous when he admitted of Les Fleurs du Mal, “I have included a certain amount of filth to amuse the gentlemen of the press. They have proved ungrateful.”

To be an edgelord, then, is to not just be provocative, but to regard provocation as an end in its own right. To not only risk but relish disapproval. The virtues of heresy have been praised by sources as diverse as the saintly Martin Luther (the “wickedest man in the world”), Aleister Crowley and the Moors Murderer Ian Brady. All believed that heretics were more spiritually pure than the conformists were.

Luther and Crowley didn’t live long enough to see the word “edgelord” come into use, but Adam Parfrey, the founder of Feral House press, and the publisher of two of my favorite books: the Apocalypse Culture anthology and Ian Brady’s The Gates of Janus, did. I never got the chance to ask Parfrey, who also founded a “fascist think tank” called the Abraxas Foundation, what he thought of the term “edgelord,” when I spoke to him shortly before his death in 2018. Still Parfrey, who also published a novel by Joseph Goebbels, was undoubtedly an aristocrat of the edge. “Upsetting people is a beautiful thing,” he said, because it gets people to think above quotidian concerns like what they’re going to buy next from the mall.

Whenever anybody calls you an “edgelord,” there’s a simple response: what would you sooner be, an edgelord or a “borelord?” In the law of oppositional signifiers, anyone who uses the term “edgelord” as an insult is almost certainly a de facto borelord. I would much sooner go to my grave having made the odd bad-taste joke than being too scared to break wind in public ever.

Because being a “lord” of any kind — see, I’m checking my privilege! — comes with a certain noblesse oblige. And the obligation of the edgelord, as I envisage the role, concerns honesty and ethics. Is that so controversial?

First, be honest with yourself. Is what you’re saying or doing really worthwhile?

And has it actually harmed anybody?

Whoever came up with the phrase “never apologize, never explain,” wasn’t a real edgelord. Sometimes the most dangerous thing you can do is put your own pride on the line and apologize when you have caused unintentional harm.

Of course, the definition of “harm” is one that borelords are always trying to move closer to their comfort zone. Don’t let them. As the arbiter of your own moral universe, your duty as an edgelord is to know how sharp you really are, so you know when you’ve actually hurt somebody who didn’t deserve it. Because bullying the weak and vulnerable really isn’t smart or edgy or cool, and usually neither is insulting your own mother (if you’re reading this, sorry again, ma’!)

But some people, who engage in certain types of behavior, deserve to be harmed.

That’s where the borelords — woke mobs who engage in “cancel culture”— and I actually agree. Pain is an effective deterrent, as are ridicule and humiliation and economic sanctions. We just disagree on who has the right to dish it out and who deserves to take it.

Often, borelords try and impose their own boring standards on other people by squealing that a piece of art or literature is “harmful.” Rarely do they ever furnish their arguments with any actual examples of who has been harmed, usually because they haven’t. Taking offense and screaming “it hurts!” is the borelord’s most notorious vanity mechanism. Like when I encounter an infant on an aeroplane, I often find their squealing more offensive than the thing they are squealing about.

That’s not to say that art or literature cannot or should not ever be harmful. I like the idea of writing a book that was powerful enough to actually hurt some people. Not oppressing minorities or bullying the weak, but hurting the vain, the venal and dishonest. Zola may have achieved this with his scathing satire of aristocrats in The Kill. Like him or loathe him, Salman Rushdie touched more than a few nerves with The Satanic Verses. Spy magazine’s pithy satire of Donald Trump, labelling him a “stubby fingered vulgarian,” obviously hurt his brittle ego, because he spent the next quarter of a century ridiculously asserting that he had “normal sized” hands. Language can hurt people, you see. Just not very often. Perhaps not often enough. Or not in the right places.

Borelords are only brave enough to fight in packs, from the safety and security of the crowd, when they know they’re on safe ground. Whereas the edgelord is willing to stare down a lynch mob, or go after a target, on his or her own.

Another key difference between edgelords and borelords is that the edgelord is fundamentally more honest. Any edgelord worth their salt will be open about their malign and selfish intentions (see the examples of Baudelaire, Brady et al). On the other hand, borelords frequently wreck other people’s lives under delusions of virtue.

If you’re reading a column by me on Safety Propaganda, in all likelihood, you already know that you’re a piece of shit. You don’t just admit it, you embrace it. Am I contradicting myself when I say, I think there’s something admirable, if not virtuous, about being honest with oneself and others?

Next in this semi-regular partnership between myself and Herr Lehrer, if there’s demand for it, I’m going to insult some other hypocrites in the literary and arts scene who aren’t as virtuous as they think they are. Why? Because I think they deserve it.

Lev Parker is the editor of Morbid Books and the chairman of the Temple of Surrealism.

Images:

Top image is Friedrich Nietzsche

Other images are courtesy of the author, depicting the various functionaries of the Temple of Surrealism

”Morbid Takes” is a collaboration between UK-based surrealist publisher Morbid Books and Safety Propaganda.

Let’s not forget about the ultimate edgelord https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesus

Excellently written, I smiled several times. Bravo