How many American artists make work about America that isn’t overly critical if not contemptuous towards American values? When googling the countless American artists that incorporated the American flag into their work, I can’t find a single example of the flag being depicted positively, without the artist’s intention of deconstructing the image to excavate some dark, hidden meaning in its iconography. Faith Ringgold’s The American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding depicts a smug white couple and a black man bleeding from his shoulder as they all lock arm and arm against the flag backdrop. Ringgold obviously meant to make commentary about the alleged racial violence that American notions of freedom are built upon. David Hammons’ African-American Flag combined the flag of our nation with the colors representing Marcus Garvey’s flag, suggesting that the red, white and blue isn’t suitable for the black Americans ostensibly oppressed by their own country. Even Jasper Johns’ Flag, a painting of an American flag made to look rustic and weathered, which could be interpreted as a pro-America image, shuns positive interpretation via the artist’s refusal to invite political interpretation at all. Despite America being the center of the global art world for more than a century, there are woefully few examples of non-kitsch artists willing to celebrate the promise and freedom inherent to the American ideal.

Until now, perhaps. Ben Werther, a New York-based artist that I became friends with last year when he joined our podcast to promote his solo exhibition at No Gallery, is entranced by America. Or at least, he finds himself perpetually seduced by a notion of America all too familiar but ultimately lost.

“I would say that it is patriotic in that it is a representation of a very stereotypical idea of middle America, or at least how people think a place like that might look,” he said to me over text message. “But as far as whether or not I am putting these images up and pointing to them and saying, ‘this is good,’ I would say that is of less interest to me. However, nostalgia as a kind of political system is of interest-and that is something that can be leveraged for the goal of stoking patriotic sentiment.”

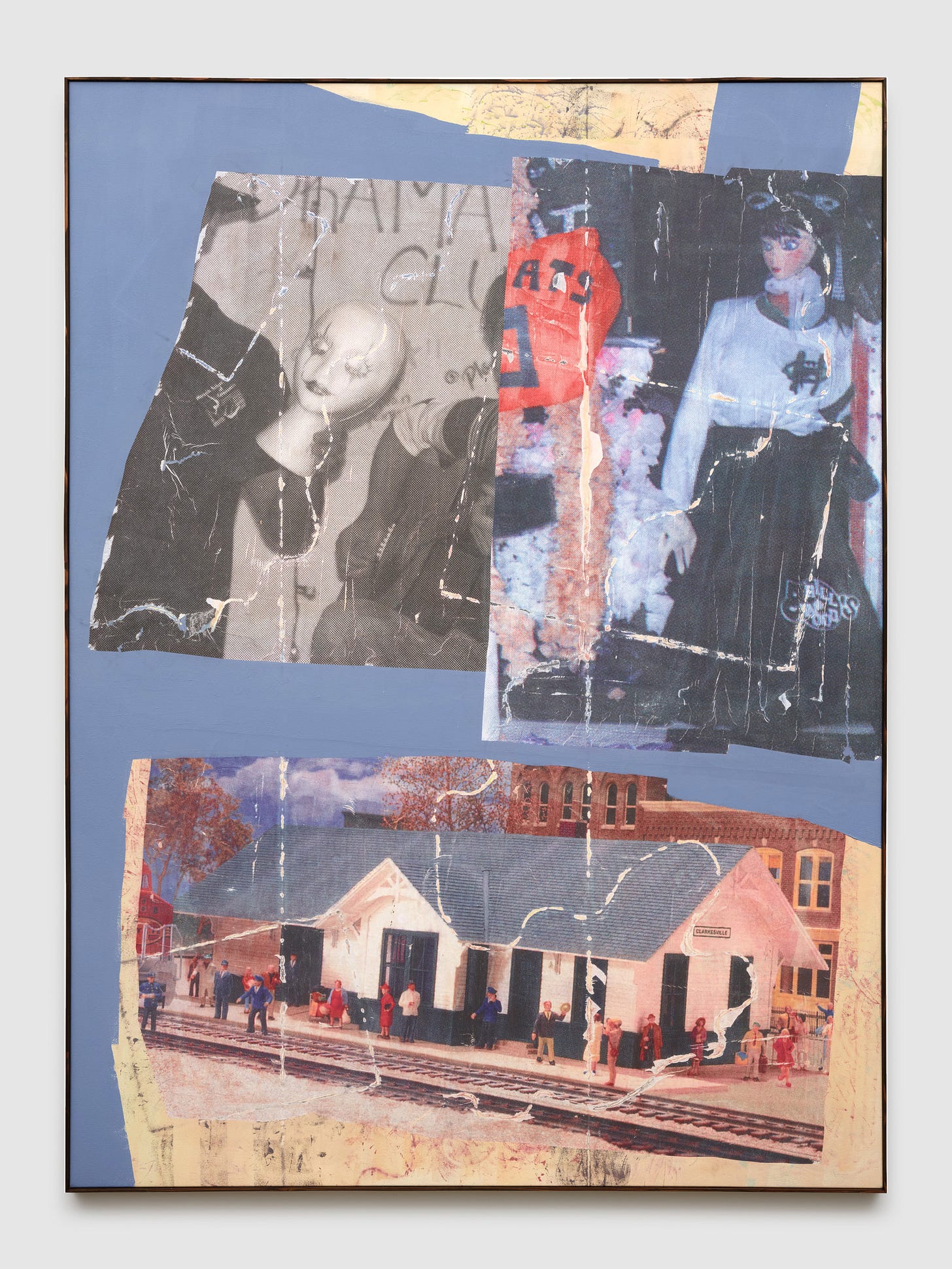

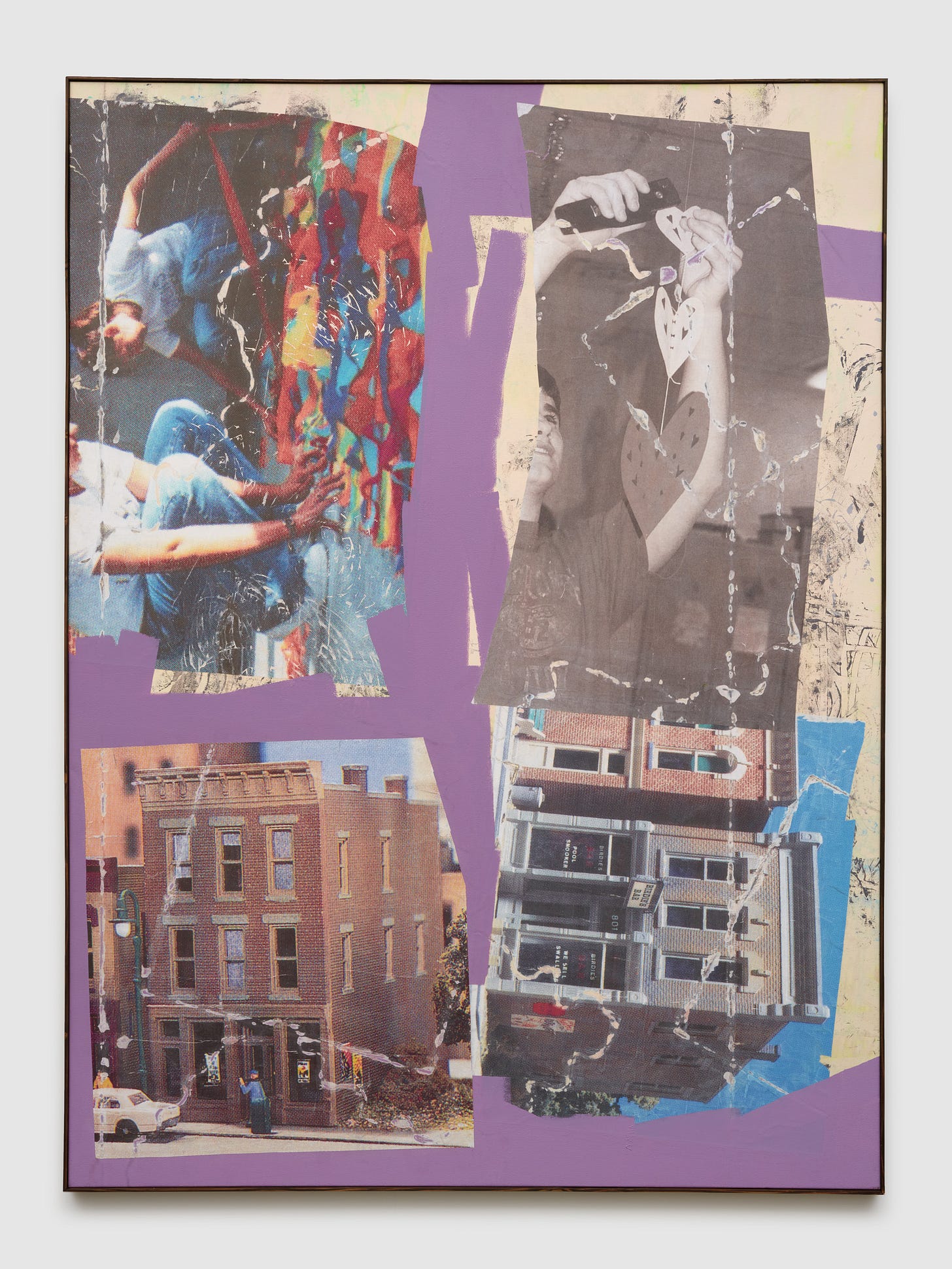

Werther’s latest exhibition and second solo show at Amanita Gallery, Townworld, USA - A New American Myth, explores the mythology of the lost, idyllic American community rather explicitly. A diligent collector who has long incorporated an anthropological practice into his art, Werther spent years collecting early-2000s high school yearbooks from antique shops, thrift stores, and yard sales in his hometown of Nashville, Tennessee. In the new works, images from the yearbooks are juxtaposed alongside scans of model train catalogs. While it sounds simply, the body of work is an elegy. It’s about what we’ve lost, about the America that we once knew, and about the country that we let slip from our grasp because, whether by our own first world privilege or elite educations, we failed to be thankful for the glorious home that we inherited. This is art about a people scorned and abandoned by God because after all that he gave us, we still didn’t quite comprehend the gift bestowed upon our people.

Narratively, the work echoes the subtext of Twin Peaks: The Return. Twin Peaks no longer exists. There is no idyllic American community, indeed there is no Twin Peaks, immune from the encroaching disintegration phenomenon of the post-digital age. The quaint small town center is littered by junkies spiking their veins with fentanyl. The small high school entrusted to bring the next generation to adulthood has been converted into an ideological brainwashing institution', where teachers are too preoccupied telling students that their heritage is evil or that their bodies are wrong to remember to teach them how to read, write and succeed. The local police that once busied themselves keeping drunks off the streets now find themselves joining task forces to deal with the Tren de Aragua problem. What even is America, anymore? Leave it to Beaver it is not.

Werther has said that the ultimate art object would be something like a time machine. Or, at least an object the wears the markers of the passage of time. One can’t deny that the beauty of a well-worn, frayed and miscolored Schott Perfecto or a perfectly beat up pair of Levi’s 501s is substantially greater than the same jacket or the same pants just purchased brand new off the rack. Werther uses paint to mimic this effect across his canvases, sometimes it looks like graffiti and sometimes it looks like natural wear and tear, but the effect is always one that reminds us of times lost and, more tragically, times never returning to us.

“The question of loss is key here because with memory there are always holes in your idea of the past,” says Werther. “And we tend to fill them in. This is the role of the miniature in my show.”

While the artist here is careful to remain open to the fact that we all over-romanticize worlds behind us, his glorification of a forgotten America past stands out in the glut of contemporary art. The vast majority of artists now are concerned with the proposition of utopian futures that are always yet to come. More often than not, artists have laid the ground work for utopian theories that have wound up being absorbed by the intelligence apparatus and funneled towards new USAID scams. Artists have the time and luxury to perpetually deconstruct reality, channeling discontent in increasingly misguided reflections. Werther asks that we pause and ask: “Was it all really so bad?”

Utopia, he suggests, just might be the world we’ve left behind. Perhaps we had it as good as we ever could, and we fucked it all up.