Safety Propagandist #2: André Coelho AKA Metadevice

Adam Lehrer Corresponds With Our Second Safety Propagandist, the graphic novelist, artist, and noise musician André Coelho

André Coelho is a Portuguese noise musician, illustrator and graphic novelist. André and I began corresponding after I discovered his noise/power electronics solo project Metadevice, which I reviewed for my regular column on noise music and philosophy, Genre is Obsolete. I quickly learned that André was a Renaissance man of rare distinction. He was previously a member of the industrial group Sektor 304, the trans-national performance art and improvisational music collective Mécanosphère, and is currently also in the ambient duo Iurta and Sensor.

After we corresponded some on the internet, André was kind enough to send me his work in graphic novels and I blown away. A phantasmagoric collaging of cryptic texts and surrealistic, haunting drawings that together yield something closer to a mood or a feeling than a traditional narrative.

Adam Lehrer: Your music seems to open a space that resembles a kind of industrial nullenvoid, pure energy. It's like everything just dissolves into space. How did you come to be interested in this kind of sound?

André Coehlo: My strategies are those of industrial music: looping, sampling, machine-like repetition, the incorporation of field recordings, altered or DIY instruments, noise, electricity.

I never had any kind of musical training, but I had this instinct to record, so my first interaction with sound was precisely by cutting loops of either my own field recordings or from other people's music and then processing and reshaping them. Looping has always been my main technique. It was only several years later that I began working with real synthesizers, and even now, I still do not completely rely on them. There is always a great deal of improvisation in long recording sessions before I can cut the most precious sections and pieces, the ones that might feature irregular variations, interesting dynamics or particularities, sometimes taking advantage of mistakes, irregularities or failures, that through repetition or occasional calculated application may find its place within a composition. But even though the strategies were akin to industrial, noise or power electronics, I never felt the need to keep strictly enclosed in those aesthetic compartments.

This logic was already present in my previous projects, namely Sektor 304, which evolved from a junk-abuse-industrial-power electronics sound towards a much wider palette of sounds and instrumentation, incorporating polyrhythmic patterns, melodic elements, diverse vocalizations and electro-acoustic handmade instruments and gadgets, adding distilled influences from early Swans to Test Dept or African Head Charge. This was further explored in my collaboration with Mécanosphère during the recording of Scorpio, which was a rather fragmented and mutant project, receptive to different approaches to form a poetic assemblage or luminous mosaic of dub-tinged bass lines, hip-hop beats, industrialized drones and synths, jazz infused horns, polyglot ghost voices and cut-ups.

AL: There are bridges between various strains of extreme music in your work. The vocals ring of Sutcliffe Jügend at times, there are allusions to ritual ambient and early industrial music. But everything collapses on top of one another. An originality is yielded in the fissure. What is your relationship to extreme and noise music? Who were the artists that your fascinations with compelled you to create? And how do you keep the material fresh?

AC: Extreme metal was something I grew up with, especially black and death metal. But I could point to three specific somewhat Y2K records that functioned as turning points: Dodheimsgard's 666 International, Satyricon's Rebel Extravaganza and the self-titled Thorns. These works were a creative pinnacle of the truly disruptive forces in black metal and held immense value in opening its canon towards a wider range of sounds without compromising the primordial violence intrinsic to the genre's second wave.

From that moment on, the need to find more extreme music capable of pushing boundaries took me right into the industrial/noise scene. I discovered Bourbonese Qualk, Einstürzende Neubauten, Throbbing Gristle, Test Dept, Deutsche Nepal, Muslimgauze, Esplendor Geometrico, Maeor-Tri, Illusion of Safety,Nurse With Wound or SPK, among other classics.

As with practically all extreme music genres, I currently find that industrial and noise music (here the term is used in its wider sense) have transformed themselves into clusters of codified formulas repeated until exhaustion, although it is still a field with enough margin and and acceptance of experimentation. Also, in my approach to music, especially now, since I operate mostly alone as Metadevice, I tend to draw inspiration from sources other than music. Studies for a Vortex, my first album, gathered a great deal of inspiration and lyrical appropriation from Ezra Pound, James Elroy, Thomas Pynchon and Allen Ginsberg, as well as several studies and documentaries on the abuse of pharmaceutical drugs, psychological disorders, alienation and violence, to invoke a state of mundane and existential disorientation. Ubiquitarchia was haunted by the ghosts of simulation, surveillance and technocratic tyranny, and was heavily inspired by Foucault and Baudrillard, as well as daily news and mainstream media, perfectly combined with the Covidian state of panic that unmasked the hegemonic tentacles of the neoliberal totalitarian hyperreality. So, in a way, industrial/noise/ambient is primarily a vehicle to express my imagination.

I guess in the so-called extreme music genres, as in every genre where pre-established canons exist, there is a great deal of pressure or tendency to correspond. But this is just another form of feeding a paradigm that already has assimilated and inoculated these “extremities” to the point of kitsch or anecdote. Any kind of impact is neutralized. How radically effective are punk aesthetics, for example? Or how shocking is fetish or sexual imagery in industrial music? If I had to pick some recent Industrial / Noise / Power Electronics projects or records that stand out among the flood, I would definitely pick Strom.ec, Grunt, IRM, Altar of Flies, Alfarmania, Wet Nurse's Thanatosis, Last Dominion Lost's Tower of Silence, Anemone Tube's Golden Temple, the latest releases of God Is War, Sutcliffe Jügend’s Slaves No More or Post Scriptvm Variola Vera.

AL: Iurta and Sensor, on the other hand, is more abstract, and improvisational in nature. What was the genesis of ideas that led to this new project?

AC: It is completely oriented as a field of interaction and dialogue. Being the last member to join the group, my interest in the project was precisely its creative opposition to what is currently my modus operandi in Metadevice.

Rather than a founding concept or idea or even a will to perform “free-improv music,” what defined this project is a specifically collective mindset. Each rehearsal and recording session opens a new possibility and narrative, a new vector, driven by our sensitivity and how it relates to others. To play improvised music such as this is to rely on instincts and to know how to operate within the possibilities of freedom. Intuition, risk, pressure, and the occasional sense of failure play a huge role here, but also responsibility and capability to support others, either with your input or your silence, all in favour of what is being created. It almost sounds like a utopian thing.

AL: Portugal is obviously a very different country than the United States, but you've also noticed that the lack of critical thinking encouraged in American schools and exported elsewhere by our powerful NGO sector is having global ramifications. Do you see this as a new version of imperialism? Are you worried that people are becoming dimmer, and less critically rigorous than in previous generations?

AC: Yes, I do believe that critical thinking is becoming an endangered species. There is a kind of lethargy which imbues the Portuguese spirit and makes us quite permeable to become uncritical or non-active people. Adding to this, we must consider the 40 years of Catholic isolationist right-wing dictatorship whose journalistic, political, and cultural censorship met little opposition, such as the clandestine action of the Portuguese Communist Party or the famous presidential candidate General Humberto Delgado, whose assassination in Spain was perpetrated by the Portuguese secret police. Besides, thirteen years of colonial war fought simultaneously in three different African countries sucked all the resources and vitality from such a small country, left deep scars in our history and in the younger generations between 1961 until 1974, the year in which a military coup d’etat ended both the war and regime. If you are interest in some literature concerning this war I would definitely recommend you two books: Os Cús de Judas by Antonio Lobo Antunes and A Costa dos murmúrios by Lídia Jorge, although I’m not sure if they have an English translation.

From 1975 onwards, we adopted the paradigm of a social democracy, after entering the European Union, and gradually turned more into a state and society driven by a neoliberal thinking that echoes the models of American capitalism. The shift into a more US imported western hegemonic paradigm, promoting materialistic seduction, consumerism, and individualism, has enhanced a feeling of dehumanization. The pandemic emphasized this. It became clear how east it is to control public opinion, especially with social media. Even radicalized or countercultural speech can be rendered innocuous once absorbed and regurgitated propaganda.

For example, while submitting uncritically to the exception principles that should be, by definition, temporary, we see them becoming rooted in the vertigo of our daily lives due to supposed crisis management (economical, terrorist, sanitary). In fact, most of the real issues regarding health care or social inequality are still being omitted without debate. This process is aided by the growing digitalization of life, making us evermore at the mercy of non-stop entertainment, hedonistic lassitude, and algorithm control. It feeds the illusion of a “real” participation and a “real” political consciousness, temporarily filling this kind of existential void and inertia we live in. It gives the sense that our voice counts, even though we are just puppets of “meme” and “hashtag” culture. This is the mindset younger generations have been growing up with and things do not seem to be getting any better. When the world and its representations are enclosed on this capitalist illusory paradigm of freedom, it becomes harder to imagine any other option beyond it.

I remember Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism made absolute sense for me. His description of the education system crisis and to what he calls the “state of hedonia” inherent to his young students mirrors what happens in Portugal: teaching, for example, has turned into a bureaucratic work inscribed in an evaluation regime that only pushes towards the degradation and devaluation of the professional aspects of education. These factors lower the demanding standards each year, thus harboring the illusion of increasingly democratic educational achievements throughout society, which don’t really exist. Now, having a degree means absolutely nothing, in both the acquisition of knowledge and professional achievement.

There are two remarks I would like to make clear: I am not anti-democracy or anti-socialist, quite the opposite. Those two concepts presuppose the existence of educated individuals, armed with critical sense, and a clear notion of the immense value and weight of individual freedom, which is, in fact, one of the main focuses of our constitution. Without a proper education system aimed at forming thinking citizens, we will always be at the mercy of power, whatever form it assumes.

So yes, perhaps this Anglo-American capitalist paradigm is a new form of imperialism as it promotes itself as the only acceptable structural system and the limit where each and every individual or society aims to achieve, the only civilizational climax.

AL: Your books, like Terminal Tower, are filled with provocative illustrations and cryptic texts. Together, they evoke a sense of fragmentation. They remind me a bit of what Deleuze found in Francis Bacon: “the logic of sensation.” They shun narrative in favor of the sensation. Could you explain this aspect of your work? Do you see these works as abstractions to any degree?

AC: Yes, the logic of sensation sounds quite accurate in my books, even though they are graphic novels that do not fully adhere to a traditional linear narrative. I focus on attaining a certain mood within the poetic theme. I would even add they contain as much abstraction as they do mystery, and to fully absorb them the reader must also apprehend mystery as being part of it. I always had a fascination with Caspar David Friedrich's Der Wanderer..., Arnold Böklin's Isle of the Dead or William Turner's seascapes, for example, due to the centrality of mystery in them.

As a formal aspect, the labyrinthine fragmentation of Terminal Tower is obvious, but it was also part of the working process. This book was made in cooperation with the writer and translator Manuel João Neto, in a back and forwards process of mutual textual and visual suggestions, reaching a point where the book achieved some sort of “self-completion.” As a result, this quite surrealistic process compromised a clear narrative line in favour of the aesthetics of paranoia and delirium, which was our aim.

The stage set for Terminal Tower is one where the barriers between the outer and the inner space crossfade. To drown it in logic and clear sense would be incongruent.|

In Acedia, this idea of fragmentation and even more present, in the juxtaposition between the main character's inner space and real-life episodes, and through the symbols or leitmotivs that slide through this duality. It is because of this logic of sensation over narrative, as you put it, that the graphic novel does not have an explicit ending, leaving it open to the main question that presides over the entire book.

All things considered, these two books are very imbued in a certain melancholic “aesthetics of disappearance,” as both main characters dissolve themselves into the mystery. My next book, Mnemosina, further explores this notion of non-narrative, focusing on the general idea of “the poetics of memory.”

AL: Acedia opens with a quote from Vollmann. What is your relationship to his work?

AC: I was first introduced to William T. Vollmann's work through Manuel João Neto, a member of Sensor and with whom I collaborated with on Terminal Tower and in the band Mécanosphère. At that time M.J. Neto was translating and about to publish Vollmann's first Portuguese editions and I was absolutely entranced by some of the excerpts. I instantly acquired Europe Central and from then on, Vollmann started representing a certain ideal: the contemporary writer who relates profoundly with his time – who is both thematically and stylistically capable of creating the most complicatedly maximalist narratives – and yet can summon the force and artistry of historically great literature, like Ernest Hemingway or Dostoevsky.

You Bright and Risen Angels was quite an important reading for me as it made me aware of certain notions of anti-progress or anti-technology that nowadays could easily be considered reactionary, but which are more pertinent than ever in building a critical spirit towards progress. His transversal focus on the theme of violence, approached in its various forms (war, poverty, misery, ecological decline) is nothing short of a hammer that shatters the glass that composes reality. It was with great pleasure that I was commissioned to create the cover for the Portuguese edition of Vollman’s Europe Central.

AL: In both of your books there are images that evoke warfare. What is your fascination with war?

AC: It is likely related to my childhood fascination with geography and history. Territory and its natural or manmade transformations occupied a great deal of my imagination and war, as a vector for transforming the landscape, entered my imagination through maps and their geopolitical limits, inscriptions, and other graphic elements. These, put together with the crude, visceral brutality of World War photos seen in books and encyclopedias, as well as my father's photo album of his service time in the colonial wars, created a subconscious perception of war containing this abstract dimension of an almost oneiric reality.

I somehow associate this “abstraction” to one of my oldest and clearest images of “real” war from childhood: myself at six, watching a live footage of Baghdad's bombing during Operation Desert Storm. There were green elongated lights crisscrossing the black void of this distant territory.

The work of J.G. Ballard that had a deep impact was the short story “Terminal Beach”, a story which illustrated “war” as an omnipresent specter. It is not “there,” only its displaced elements: the concrete bunkers, the watchtowers, the detonation areas. War is not real, it is only a test ground, a simulation. The real isolation and the real destruction are within the character's mind and perception.

This melancholia and displacement and their association with war was perhaps instilled in me by Paul Virilio's Bunker Archeology and Maurice Blanchot's The Writing of Disaster. There is a dream-like dimension to Virilio's photographs of the Atlantic Wall, an alluring stasis. To watch this type of construction is to invoke the absence of time through the paradox which is “the ruin of the future”: an antithesis of “architecture as a stage for life.” Furthermore, I should name Julien Gracq's novel The Opposing Shore, which explores the fortress's phantasmic properties as a surreal space of ominous projections of solitude, anxiety, and rumor at the limits of territory.

AL: Who are the artists and writers that you think about the most when composing these books?

Andrei Tarkovsky is the name that first comes across my mind when asked this question. Not only for his films, which I praise above all other cinema, but also due to his marvelous book Sculpting in Time, which is as much of a treatise in art in general as it is about cinema. I should add Bataille, T.S. Eliot, Novalis, Tonino Guerra and W.G. Sebald in literature and poetry. Nico's Desertshore, The End, and Fata Morgana, as well as Scott Walker records have been precious companions. As for graphic novels, I always come back to Edmond Baudoin, Lorenzo Mattotti and Alberto Breccia, as well as Alain Alagbé, Michel Matthys and Vincent Fortemps. And, of course, artists such as Arnold Böcklin, William Turner, Rothko, Roj Friberg, William Blake, Zhang Daqian, Antoni Tàpies, Anselm Kiefer, Gunther Brüs, Francis Bacon, Max Ernst, Otto Dix, Gerhard Richter, Kathe Köllwitz…, and at this point the list could go on forever. Now that I think of it, most are rather classic and perhaps obvious, but I believe that there is something universal and intemporal which is transversal to all of them. Perhaps a capacity to express the representation of a dimension that goes beyond the limits of the mundane.

AL: Given that we live in a time of discourse policing, reactionary conformity, and repulsively performative politics, if you had a time machine, where would you go (I'd go to Paris in the 1920s and join and get kicked out of the Surrealist Internationale to then become an enemy of Bréton and start a secret society of occult communists looking to use sorcery to imbue class consciousness into the proletariat, but that's just me).

AC: This is an interesting, yet tricky question. If we could choose, our position would always be one of advantage.

I believe I'm there with you, preferring this period between the two Great Wars. It was one of huge dynamics, turbulence and, perhaps because of it, also very creative and a lot less Manichaean as we often portray it. It probably felt as living in the ruins of the old world and still trying to realize the traumatic impact of technology and modernity. Yet, it was still a world which held something that escaped modernity, where the vortexes of the future had not engulfed everything. It was the world of Ezra Pound, TS Eliot, Hemingway, Hilda Doolittle, George Bataille, the surrealists; a world in turmoil that I would embrace only to reject it at the expense of becoming some kind of rural anarchist with anti-materialistic inclinations somewhere in southern Europe. A question such as this reminds us that we always had conflicts, censorship, difficulties; and that power has always shaped what we are. Today, the danger is that its reach is perhaps more dissimulated and fluid with the ability of making us evermore participant in its game, but it is up to us to try not to become corrupt or conformed within our means.

IMAGES

1. illustration by André

2. André Terminal Tower

3. Mécanosphère

4. Satyricon

5. Einstürzende Neubauten

6. Ezra Pound

7. Alfarmania

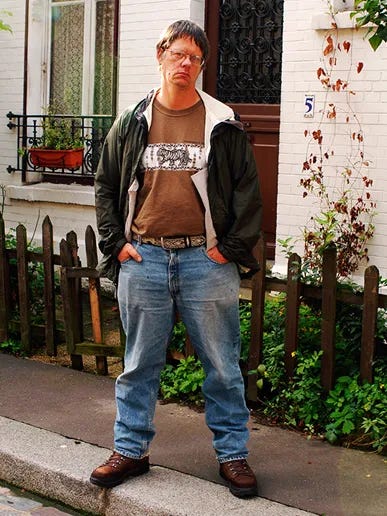

8. Humberto Delgado

9. Mark Fisher

10/11. André Acedia

12. William T. Vollman

13. Operation Desert Storm

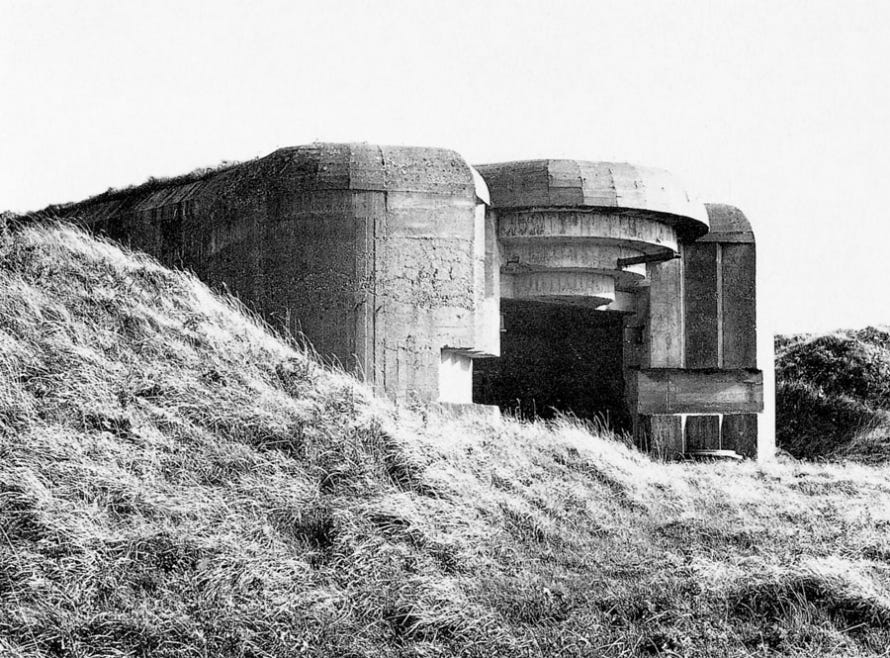

14. Paul Virilio Bunker Archeology

15. Tarkovsky Stalker

The Safety Propagandist interviews are a series of Email correspondences between artist, writer and Safety Propaganda curator Adam Lehrer with artists, musicians, writers, filmmakers, dissidents, crackpots, sorcerers, outsiders, weirdos and more. The courageous ones. The ones who won’t be silenced.