The Comedown, by Udith Dematagoda

Udith Dematagoda on the drugs, the comedown, and false notions of the divine

…hashish reveals nothing to the individual other than himself […] I will beg them to observe that the thoughts from which they expect to draw so great an advantage are not in reality as beautiful as they appear under their momentary transfiguration, clothed in magic tinsel. They belong to the earth rather than to heaven….

Baudelaire, Le Poéme du Haschisch

In Glasgow during the mid-2000s, taking ecstasy was so widespread that it essentially served as a mandatory rite of passage. This was probably a result of its wide availability, cheapness, and an anarchic electronic music scene that I suspect no longer exists in the same form. I took a lot of ecstasy and other drugs in my late teens and early twenties but gave up taking them around the age of 25. I have also taken LSD and other ‘psychedelic’ drugs on several occasions but feel, in retrospect, that taking ecstasy was the more formative experience. In the past two decades, there have been some half-hearted attempts to provide something in the vein of a ‘materialist analysis of the club space as a vector for collective liberation’, or other such theories. They speak to a rather desperate ‘collective’ desire to see non-productive and self-interested recreation as politically efficacious. For my part, I’ll freely admit, I simply liked taking ecstasy and going to techno clubs because it was fun and ‘cool’…and all of my mates were doing it. In the intervening years, those things have ceased to be the case and the little enthusiasm I had for techno music immediately evaporated as soon as drugs ceased to be a factor.

I found negligible inspiration in clubs and certainly no ‘collective liberation’ to speak of. And if at certain points I feel some nostalgia for that period, it’s only because nostalgia is a longing for an old wound. The only formative memories that persist in my mind are that of the ‘comedown’, those abrupt moments of fall from the vertiginous heights stimulated by an artificially inflated brain chemistry. I can still observe some of those moments from that period with eidetic lucidity, despite being so high that concrete details elude me. In one I was at the Arches, a dark and cavernous club underneath Glasgow Central Station, dancing with my girlfriend at the time. We were alone in the middle of the dancefloor surrounded by countless others when the song “Heartbeats” by Swedish electronic duo The Knife came on, and suddenly the entire hall was saturated with a damp and shimmering blue light. The air hung heavy with an exquisite and melancholic sense of triumph. For a brief few minutes, I felt invincible. But almost as soon as the song stopped, the comedown had kicked in, and I was gripped by feelings of utter dejection. That lachrymose song which I remember she loved (and I was indifferent to until that moment) was, like much else from that period, speculatively nostalgic: sentimental in advance of being immediate. I suspect this memory would have been moving despite my intoxication, yet somehow, I can focus on little else than the transience of that high, and the cruel inevitability of that low.

From first to last, each time effectively the same in texture yet somehow cumulatively more dismaying, I don’t think anything has had more of an effect on my worldview than those awful moments of chemically induced disenchantment. Perhaps the specific terror lies in the dissonance between extreme states of warm elation obtained with too much ease, followed by an instantaneous shift to an uncompromising and cold reality. It is a very peculiar reality, one cloaked in feelings of intense unreality - where it becomes suddenly difficult to distinguish between the two. This explanation makes more sense to me now, with the knowledge of what would transpire in the intervening years. I could sense a disruption within this emerging shadow play of reality and unreality even then, in those early days which seem now to have been freer, more unobserved and idyllic…knowing now that, soon enough, those two states of reality would begin to fold over, and over, one another.

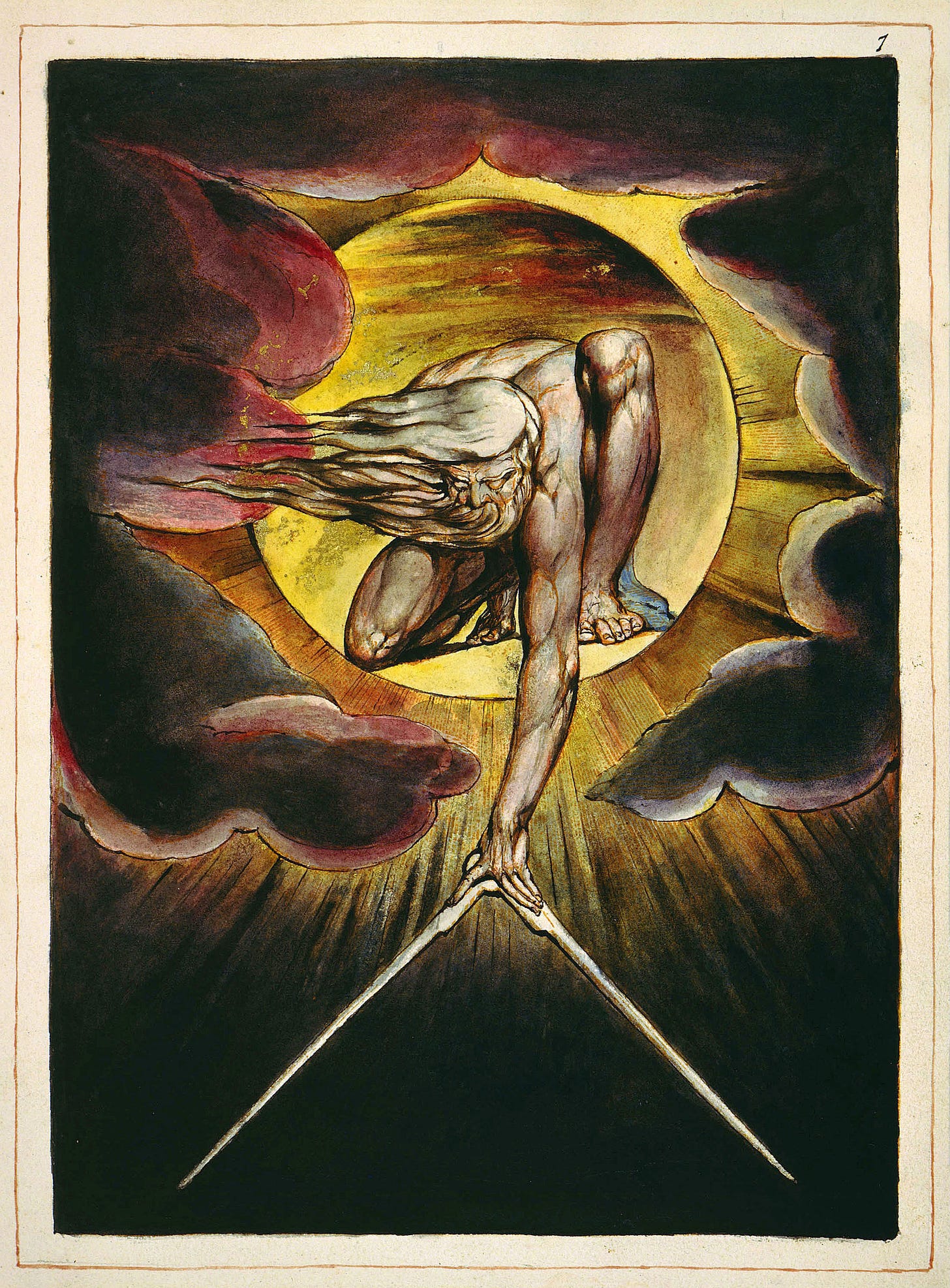

Though the comedown is exacerbated by a heightened sensitivity to cold and other unpleasant corporeal sensations, its effect is fundamentally metaphysical. The comedown confirms for us the pitiful extent of the world; that any ascent to a plane of pure ecstatic pleasure can only be achieved through a cheap alchemical trick. The first time I encountered this feeling, being young and particularly sensitive, it took two weeks to come to terms with what I had experienced, and all of my limited resources to think of anything other than how pointless it was to keep living. Much has been written about drugs and transcendence, but little about the fatal knowledge that they inculcate on the limits of the world and existence.

Purportedly ‘interesting’ writing about drugs focuses on substances that produce psychoactive and hallucinatory effects. Given their historical connection to shamanic rituals, those substances most capable of imbuing the experience of intoxication with profundity, or something approximating ‘spiritual enlightenment, loom large in the imagination. A distinct type of secular theology has developed around such accounts, starting in the early twentieth century and reaching its zenith in the 1960s counterculture. Un-diminished by the dark excesses of that uniquely prosperous decade, they continue into the present. In recent years some original work has come out of this tradition, such as Rob Doyle’s novel Threshold and Adam Lehrer’s Communions, but in my view, this is because they resist the urge to indulge in the usual platitudes, and in any case, their real subject isn’t drugs. Many of the recurrent platitudes of drug writing can be traced to Aldous Huxley’s essay The Doors of Perception and its companion piece Heaven and Hell. Huxley maintained that his experience of taking mescaline in a laboratory in 1953 was neither ‘agreeable nor ‘disagreeable’. ‘It’, he maintained, ‘…just is’:

Istigkeit--wasn't that the word Meister Eckhart liked to use? "Is-ness." The Being of Platonic philosophy-- except that Plato seems to have made the enormous, the grotesque mistake of separating Being from becoming and identifying it with the mathematical abstraction of the Idea. He could never, poor fellow, have seen a bunch of flowers shining with their own inner light and all but quivering under the pressure of the significance with which they were charged; could never have perceived that what rose and iris and carnation so intensely signified was nothing more, and nothing less, than what they were—a transience that was yet eternal life, a perpetual perishing that was at the same time pure Being, a bundle of minute, unique particulars in which, by some unspeakable and yet self-evident paradox, was to be seen the divine source of all existence.

What Huxley was conveying is in a similar vein to the phenomenological concept of the Lebenswelt posited by Edmund Husserl in his The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology (1936). The Lebenswelt is a ‘lifeworld’ of inter-subjectivity, of shared knowledge, perception, and experience. The concept has always struck me as distinctly Protestant in its pragmatic account of what was previously the domain of religious mysticism. Indeed, palpable in Huxley’s account is something of that distinctly Anglican brand of agnosticism and atheism, of which Richard Dawkins is only the most recent exponent. The most insightful critic of Huxley’s drug writing was the noted scholar of Eastern religions Robert Charles Zaehner, who also took mescaline in a laboratory setting, but to fewer ‘enlightening’ results. In his book Mysticism: Sacred and Profane (1957), Zaehner wrote an extended reply to some of the claims Huxley made about his mescaline experience.

As Zaehner maintains, the views expressed by Huxley in The Doors of Perception are the logical conclusion of a belief that all forms of mystical experience, and thus all religions, are orientated towards the same goal, and are essentially the same. This popular belief, Zaehner notes, was best summarised by Professor E. G. Browne, eminent scholar of Persian civilization and Chair of Arabic at Cambridge:

There is hardly any soil, be it ever so barren, where it [mysticism] will not strike root; hardly any creed, however stern, however formal, round which it will not twine itself. lt is, indeed, the eternal cry of the human soul for rest; the insatiable longing of a being wherein infinite ideals are fettered and cramped by a miserable actuality; and so long as man is less than an angel and more than a beast, this cry will not for a moment fail to make itself heard. Wonderfully uniform, too, is its tenor: in all ages, in all countries, in all creeds, whether it come from the Brahmin sage, the Greek philosopher, the Persian poet, or the Christian quietist, it is in essence an enunciation more or less clear, more or less eloquent, of the aspiration of the soul to cease altogether from self, and to be at one with God.

That the use of psychedelics were for Huxley an efficacious form of self-medication, a palliative, is borne out by the fact that on his death-bed he requested that his wife give him an injection of LSD, presumably to ease his journey into the beyond. This casts no small measure of doubt on the credibility of his earlier mescaline-induced epiphany. If he believed so strongly that mescaline allowed him to glimpse the divine source of all existence while living…then why take it on the very threshold of death, where all questions would finally be answered, all doubt removed, and all would be revealed?

It is well to note that Aldous Huxley, like his brothers Julian and Noel (who committed suicide) reportedly suffered from intense manic-depressive episodes. As Zaehner notes, the official medical use of Mescaline at the time was to approximate madness. (Also as a means of psychological torture during interrogation – as demonstrated by the MK Ultra program). Indeed, the opportunity to confront one’s madness in a controlled manner might be enough to convince many of us that our everyday psychological ailments are somehow inspired, perhaps even divine. To reach these conclusions, however, there must be some form of pre-existing will. Baudelaire’s insight that drugs can reveal nothing to a man but himself is apt in this regard, for the experience which Huxley attempted to convey provides more insight into his own temperament than it does any sort of universal truth. Pensive, and introspective, Huxley’s temperament was characterised by an acute sense of psychological isolation and solitude, as he makes clear in The Doors of Perception:

We live together, we act on, and react to, one another; but always and in all circumstances we are by ourselves. The martyrs go hand in hand into the arena; they are crucified alone. Embraced, the lovers desperately try to fuse their insulated ecstasies into a single self-transcendence; in vain. By its very nature every embodied spirit is doomed to suffer and enjoy in solitude. Sensations, feelings, insights, fancies— all these are private and, except through symbols and at secondhand, incommunicable.

Huxley, and others, sought through drugs to transcend the ego’s isolation, to situate themselves within a holistic and all-encompassing state of being (‘at one with God’). In this particular vein, Zaehner’s most penetrating criticism of Huxley is a very basic one: this is an utterly profane type of mysticism (‘natural’ as opposed to ‘super-natural’) simply because it requires drugs to facilitate an altered state of consciousness, rather than disciplined spiritual practice and contemplation. The taking of drugs merely represents the urge, at that time and since, to attain spiritual insight without any form of discipline, work or effort. This instrumentalization of the psychedelic experience has reached its logical conclusion in the contemporary moment, with the tech nerd plutocrat, who treats psychedelics like the asinine book summary apps they seem to be so fond of. They are merely shortcuts to insight and trivial ambitions, which don’t stretch beyond new and unorthodox ways of leveraging technology for parasitic ends. My experience of psychedelic drugs coincided Zaehner’s observations. The closest I’ve come to moments of epiphanic realisation, where the texture of time and space unravels before one’s eyes, have been through prolonged periods of silent meditation and contemplation…or indeed in moments of uncanny sublimity experienced whilst entirely sober; while going about everyday tasks, and often while doing nothing much at all. The comedown, on the other hand, imparts a different lesson entirely – the knowledge of which served as a starting point for Aldous Huxley. His own ‘grotesque mistake’ seems to have been the attempt - unsuccessful in the end – to seek escape from this knowledge,

In Vladimir Nabokov’s fourth novel The Eye, like in many of his earlier works, we can observe later and more sophisticated narrative devices as rough prototypes. After suffering humiliation, an unnamed émigré narrator in Berlin decides to commit suicide but bungles the attempt. Unable to accept his failure, he convinces himself that the afterlife consists only of being an unseen observer in the last environment where one lived. He thus wanders around Berlin only slightly modifying his routines, and begins to frequent the household of an aristocratic émigré family. He is fascinated by the family’s new acquaintance, an enigmatic young man named Smurov, who is competing with Colonel Mukhin, a former White Russian army officer, for the affections of the family’s youngest daughter Vanya. The invisible narrator is fascinated Smurov’s elegant appearance, mannerisms, and sophisticated comportment. He suspects that Sumrov’s quiet and unassuming manner belies a fascinating personal history. The narrator believes that Vanya is in love with Smurov. However, Vanya is actually engaged to Colonel Mukhin and all of the fanciful embellished stories that Smurov recounts are merely a source of awkwardness for everyone present, aside from the equally deluded narrator. Both Smurov and the narrator are – of course – the same person. One day at the family’s apartment, after Smurov has loudly related a fabricated story of his escape from the clutches of Communist partisans at the train station in Yalta, everyone is apparently in a state of shock and awe at his bravery:

Silence. Mukhin opened his gun-metal cigarette case. Evgenia fussily bethought herself that it was time to call her husband for tea. She turned on the threshold and said something inaudible about a cake. Vanya jumped up from the sofa and ran out too. Mukhin picked up her handkerchief from the floor and laid it carefully on the table.

“May I smoke one of yours?” asked Smurov.

“Certainly,” said Mukhin.

“Oh, but you have only one left,” said Smurov.

“Go ahead, take it,” said Mukhin. “I have more in my overcoat.”

“English cigarettes always smell of candied prunes,” said Smurov.

“Or molasses,” said Mukhin. “Unfortunately,” he added in the same tone of voice, “Yalta does not have a railroad station.”

This was unexpected and awful. The marvelous soap bubble, bluish, iridescent, with the curved reflection of the window on its glossy side, grows, expands, and suddenly is no longer there, and all that remains is a snitch of ticklish moisture that hits you in the face.

With Smurov’s bubble of ecstatic bliss now burst, the uncomfortable materiality of his predicament suddenly becomes painfully apparent:

During tea, Smurov made an agonizing effort to appear gay. But his black suit was shabby and stained, his cheap tie, usually knotted in such a way as to conceal the worn place, tonight exhibited that pitiful tear, and a pimple glowed unpleasantly through the mauve remains of talc on his chin.

Smurov is indeed mad, and he would not be the first nor the last of Nabokov’s infamous madmen. Nabokov was not mad, however. His purported synesthesia aside, the signal characteristic of his work is an ability to richly convey what Vladimir Alexandrov describes as the ‘Otherworld’, despite being of a sober temperament, and particularly disdainful of drugs and drug writing. The near-universal appeal of Nabokov’s magisterial prose lies in this ineffable aesthetic quality. Within the somewhat predictable narrative conceit of The Eye I always found something surprising about this one moment, comparable in texture to that of the ‘comedown.’ It proved to me something which I long suspected: that the drugs themselves – perhaps all drugs - are ancillary to the realisation that they facilitate. Not of transcendence, not of the divine source of all existence, but instead of the awful knowledge of its potential nullity; the ‘absolute void that lies behind the last veil of horror’, to quote Ernst Jünger in the The Adventurous Heart. It is something which, once apprehended, is difficult to forget. A disenchantment far removed from transcendence, but which must necessarily be experienced in solitude, and is itself incommunicable.

For more regular essays, subscribe to Udith’s personal substack Immanent Dissolution

Udith’s new novel ‘Agonist’ is now available here