THE DAY THE MUSIC DIED, by Lev Parker

Ten Thousand Apologies: Fat White Family and the Miracle of Failure by Adelle Stripe and Lias Saoudi torn to shreds by Lev Parker

That the artist is not their art might well be the only rule of art-making; it’s what grants permission to march across the borders and look back at your position in the universe with fresh perspective, it’s what lends it critical power. – Lias Saoudi, Ten Thousand Apologies, p. 285

The other evening, I received a message from somebody I befriended in a foreign city when I spotted his Fat White Family tshirt. We initially bonded over our mutual appreciation of the London rock band who, at that point, were still a very niche concern with a cultish following. Fast forward to March 2022, and the fellow Fat Whites ultra, who has also become a part of the band’s extended “family”—renting out his apartment and “lending” them money for drugs—wanted to know if I’d read it yet. “I’m thirty percent done,” I replied, plonking it down next to the jug of kratom whose murky, addictive contents pinned my pupils. And what did I reckon? On the coffee table of my seaside studio, where I now live a couple of miles from the original drummer-in-exile who gave me the copy of this “dreaded tome” that paints him and his former bandmates in a less-than-flattering light, I lifted my iPhone and thought several times — as I’ve been told is wise — before communicating what was on my mind. “He’s done the unthinkable…” I replied. Was it really fair to offer any kind of opinion on Lias’s book before I’d reached the end? The trouble was, I didn’t know if I was ever going to get to the end. “Has he done what I barely thought possible?” I mused, wincing. “Has he actually made it boring?”

I would like to reassure Lias, who I know is reading, that despite my attention-deficit disorder and extremely low tolerance for boredom, I finished Ten Thousand Apologies, the Fat White Family story released on White Rabbit books (a division of Hachette), and it had a rather profound effect on me in the end.

Upon first contact, the most striking feature of the text, co-authored with Adelle Stripe, is that it is very much authored. To appreciate the scale of what my dear old pal has constructed here, you have to understand what the writerly procedures are for non-fiction biographies, or tales which for legal reasons claim, like this one does, to be a work of “fiction” based on fact.

The most common way to write an autobiography is dictating the story to a ghostwriter, usually a novelist or journalist, who turns hours of interviews into a coherent narrative, usually told from the subject’s perspective, in an approximation of their speaking voice. Around 2018, as the band were gearing up to release their third album, Serfs Up!, Lias actually came round to my house in Peckham and began the process of dictating his autobiography. He lay on my couch in a pair of comedically small “Babiator” sunglasses and I interviewed him about his childhood and the few incidents in his life he had not already told me about at length. Later that year, I published some of these recollections in the band’s “official tour programme,” a lo-res publication knocked together in the style of 1960s football fanzines, where Lias’s “captain’s column” was “ghosted” in the style of commercial non-fiction—a taste of what his “autobiography,” written by me, would look like. He was clearly not impressed with the cheap-and-cheerful results, as we never mentioned the subject of his autobiography again, and a little while later, I learned that he had hooked up with the novelist Adelle Stripe, who was assisting him in some way.

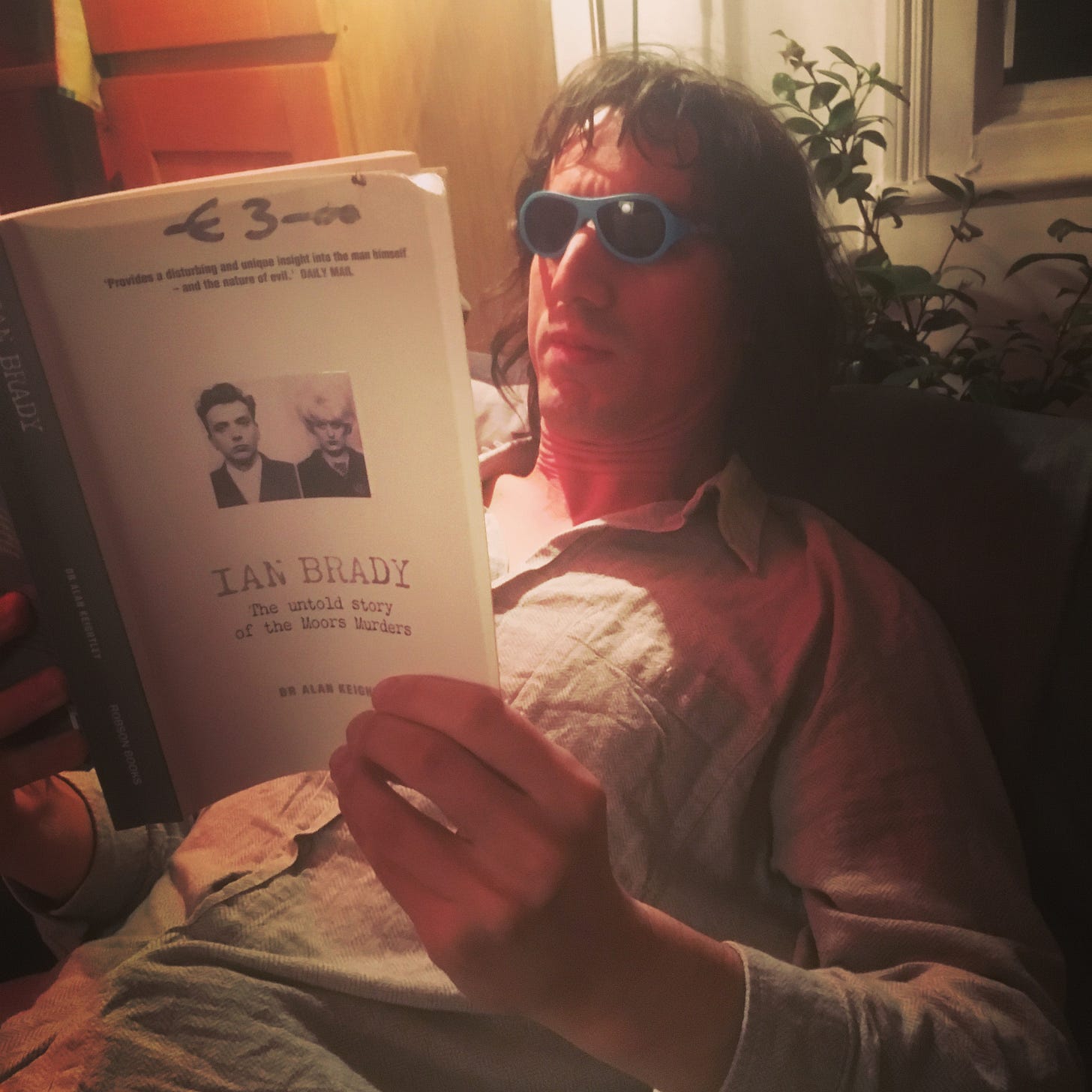

Stripe’s previous work was a historical novelization of the life of “working class” British playwright Andrea Dunbar, which doesn’t appeal to me at all—not because it’s good or bad, but I have literally never read, and have no interest whatsoever in writers’ biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, etc., unless the author also happens to be notable in some other field, such as murdering people. Stripe’s style is heavily indebted to the British nonfiction writer Gordon Burn, whose “novelization” of the life of the Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe, surprise-surprise, I have read! Stripe got in contact with me last year as part of her research. When she explained the method she was using to accumulate the material for the bulk of the book—compiling eye-witness accounts into a third-person omniscient narrative akin to Burn’s “true crime novel”, without attribution—to run alongside Lias’s own memoirish reflections, I declined to participate, and requested that I did not feature in it, a request I took as granted.

It was with some surprise, then, when my overseas pal sent me a screen grab of Ten Thousand Apologies: “You are in it…” Indeed, I do make an appearance or two, both in person and in plagiarism, but that wasn’t the only disappointment. My fellow reader wasn’t won over by the third-person narrative, the “novelization” of characters and events. Perhaps the pivotal moment in the story is the coming together of Lias with his songwriting partner Saul Adamczewski. Here’s how it’s rendered:

They made a terrible din, but [Lias’s previous band] the Saudis had some of the best lyrics Saul had ever heard. When they eventually supported the Metros a few months later, Saul stood by the stage with his mouth wide open. He was completely blown away by the performance. Saul knew from that moment that his own band was over, and in Lias Saoudi he had finally found his foil.

“Is that really what happened?” the reader asked me, who knows how scabrously Saul talks and thinks. “Is that really what Saul was thinking at the time? I’m not convinced at all…”

There are lots of other moments where I could see the “sausage” being manufactured out of storytelling clichés. Like at the gig during the Bataclan terrorist attacks, Nathan supposedly said out loud, “It wasn’t just the madness outside…two acts of violence at once. Maybe the universe was trying to tell us something.”

That was after the producer Liam May made an appearance as a character with an uncanny ability for saying what the narrator wants the reader to see: “You’ve come a long way from when we last did this though…Now you’re swanning around with New York glitterati. I don’t know if you’re quite prepared for the different realm…Where’s Saul anyway? Because we’ve been here since ten, recording. And it’s now almost five. The studio gets shut down in half an hour.” Reader, I dare you to guess who should turn up the very next instant.

I’ve spoken to a few people featured in the book or close to the subjects who claim that it “doesn’t ring true” to them, although they don’t have the literary vocabulary to explain why. I’m not a professional critic or theorist, but I can provide some insight into how the sausage was made, and why some bits taste funny.

From the first sentence, Ten Thousand Apologies sounds like a different time and place from the thing it describes. Plunging us into the protagonist’s family home and setting the scene slowly, it sounds very much like storytelling, but not one of those trashy ghostwritten memoirs the proles read where everyday vernacular is rendered on the page, and nor does the narrative voice sound like it belongs in the same room as the characters—it’s coming from the 1950s or even before, with a distinctly pre-pop-music crackle to it, the kind of thing you might hear on BBC Radio 4’s Book at Bedtime if there weren’t so many crystal-meth references.

The first time I ghostwrote a book, when I was figuring out how to get the voice right, I developed a maxim: if it looked or sounded like writing, chuck it out. In Ten Thousand Apologies, Stripe appears to have taken the opposite approach. Only if it looks and sounds like writing then it must be good.

The first several chapters are devoted to Lias’s family, then his school days, all labored with unnecessary details and the dramatization of mundane household events. On page one, they’ve ticked off conventional descriptions of the protagonist’s bedroom, his mother’s cooking and his father’s temper. By page 90 he’s still only at Slade Art School and hasn’t made a tune yet. While the stylistic experiment with social realism did nothing for me—indeed, I skimmed the early chapters—I snagged by page 100 what he was doing, and while it may not have been to my taste, I admired his shamelessness.

If Lias or anybody else our age writes their life story, that’s ridiculous enough. But he hasn’t done that. He’s released a work of historical literature about himself.

Regardless of its frequently dubious quality, the severity of the project is impressive. Step back from the luxurious red hardback, all its many hilarities and flaws, and let these facts sink in: this monster mash-up between a historical novel and nonfiction self-exploration, The Life and Opinions of Lias Saoudi, also featuring some current and previous bandmates (whatever), didn’t crawl onto the Sunday Times Bestseller list by itself. Our man lured a serious novelist and a reputable publisher into realizing his grand vision, and got Mark Lanegan and Rolling Stone to praise it. Thousands more people have bought the bullshit, and that alone is remarkable.

In this context, the communist imagery on the cover takes on a deeper, more troubling resonance. Ten Thousand Apologies is Stalinesque in its ambitions. Although the content is more humorous and self-deprecating than works such as Young Stalin, it makes you wonder…With the Ukrainian equivalent of Larry David currently waging a surprise lo-fi war against Russia, it makes me wonder, has smearing yourself in shit, taking a lot of drugs and gurning become a stepping-stone to political power? Is ironic self-awareness part of the audition for leadership in the age of social-media idiocy? I make no grandiose predictions about Lias’s future, although given how satire so frequently underwhelms postmodern reality, and his endeavors nearly always exceed my expectations, the reader should not rule out the possibility of Ten Thousand Apologies becoming a Mein Kampf for the post-Trump generation.

The easily manipulated masses who buy this book won’t understand how psy-ops work, so the smarter ones with any critical faculties whatsoever—those who don’t just nod and chew along to whatever shit they’re fed without asking any questions—will perhaps wonder why (WHY?) did he make such a bland meal out of these spicy ingredients? Given how slowly this clown-car Mein Kampf starts, I reckon the charity shops will be full of them by Christmas. Which is a shame, because once it gets going, the story of the band that took rock music back into the abyss and out the other side would require Stalinesque censors for it not to wind up being as fun as the band’s many bawdy capers.

When the dialogue is good, the voices of Saul, Nathan, Lias, Adam, Dan and Curly Joe burst out of the stifling retro-novelistic backdrop. The boys are in the room, leaving their shoes in the fridge, ripping Sean Lennon’s ranch to shreds, demonstrating precisely why the depraved Fat White mode of existence — even at the cost of mental illness, drug addiction and poverty — might, when all is said and done, be preferable to the safer alternatives. And that’s true no matter how well or badly it’s written about after the fact.

There’s a particularly grand moment at the end of the book where Nathan takes helm of Serfs Up! and confronts the band with the ideological contradiction in their lo-fi aesthetics, which by this point are costing them thousands of pounds to produce in a tailor-made studio. “Middle-class people make it sound like they’re penniless,” says Nathan. “They’re emulating the sound of people who can’t afford studios. Working-class people want music to sound polished and elegant…Cheap noise doesn’t happen in hip-hop or grime. It’s slick and futuristic. That’s the record I want to make.” (Elsewhere, Saul has glibly said his role in the Fat Whites was to make them sound less like a shit indie band and he failed.) It’s deeply ironic that one of the most coherent cultural critiques in the book — and there are many, especially in Lias’s sections — is dismissed by the bourgeois novelistic narrator as Nathan’s “ketamine theorizing” that “only made sense to himself.”

Because Nathan’s critique of musical styles also applies to literary aesthetics. If Ten Thousand Apologies is dull and boring in parts, it’s because middle-class people expect books to be dull and boring, or at least long and somewhat tedious – certainly not too colorful or exciting. You can have your sausages, but you must also eat your vegetables! Like grammar schools, literary style keeps the masses at arm’s length.

It’s a shame that a band who set out to offend bourgeois tastes as a pseudo-paramilitary group called Yuppies Out! and an album titled Champagne Holocaust have been so thoroughly co-opted into the stylistic palette of the nostalgia industry. Never mind the bollocks, here comes the artisan cupcake of storytelling, with its bourgeois narrator serving the Fat White Family in a style that makes them seem less offensive to the kind of people who go to Jamie Oliver and Alex James’s music, wine and cheese-tasting festival.

Lias openly admits he now strives to cut a “slightly more reasonable figure in culture” with justifiable motives: “The fear of having to hobble into middle age trapped in penury, rapping at my non-existent front door.” That’s a quasi-Dickensian way of saying he knows where his bread is buttered. Unlike me, he knows not to bite the hand that feeds him, or at least give its five sweaty fingers a seductive lick while he’s doing it.

Like me after reading his book, we both question whether we have wrecked our lives doing the thing we loved, or at least thought we loved. In my second without-consent appearance in Ten Thousand Apologies, I’m in the comedown party at the end of the Fat Whites’ 2016 Songs for Our Mothers tour. To my mind, the band that started in the Queens Head pub over the road had completed its remarkable journey in a little over five years by selling out Brixton Academy. “Well that’s that, what are you going to do now?” I said, and Lias cursed me from the bitterest depths of [his] heart. I remember that awkward moment after the Brixton Academy show, and I was even more of a downer than he recalls. I told him to walk away from the band, because the trajectory from there was almost certainly a downward spiral. Given how the third album turned out to be a banger, I was happy to be proven wrong, or at least premature in my estimation of the day the music died.

At the end of Lias’s undeniably funny story, I came to appreciate the benefits of selling one’s soul, and not just the money they give you for it. Art can be awfully heavy when you own all the rights to it. Every book or magazine from the publishing equivalent of my friends’ punk band now feels like one too many, yet I seem unable to stop making them. Unlike the Fat White Family, who went semi-legit and can now draw a line under particular styles and antics, books stamped with the ominous bent-spoon logo have never been regarded as marketable commodities. So I don’t yet have to choose whether I become a museum piece, I just get to envy the storage space. With no property, no paperwork, no staff, I’m livin’ the goddam hippie dream with nothing to lose, how do I get away from it?

Lev Parker is the editor of Morbid Books and the chairman of the Temple of Surrealism.

Excellent piece of amusing critique and reminiscing.