The Ideological Aesthetic: the ‘Political’ as inevitable and Epiphenomenal PART 2: Hyperpolitcization, by Udith Dematagoda & Christos Asomatos

Why is everything an 'aesthetic'? Two writers explain... Part 2 of 3

Following this line of thinking, we can therefore arrive at a formulation which contradicts the more commonplace assumption that the prevalent economisation of contemporary life has shrunk the penetration of politics into sociocultural matters. This is also a formulation which, seemingly inadvertently, invokes Carl Schmitt’s own understanding of the structure of the political and its relation to the other fields of social life:

The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy. (Schmitt, The Concept of the Political 26)

Schmitt, famously, defined the fundamental condition of the political as the ability of a distinction to mobilize two entities into a grouping of friend and enemy. This constitutes, Schmitt disclaimed, no “exhaustive definition” of the political but its specific criterion. Although the writer’s early attempts at delineating the concept were marked with certain inconsistencies in terms of its relationship to the other spheres of human thought and action— inconsistencies which Leo Strauss identified already in his critical review of The Concept of the Political in 1932— Schmitt gradually moved toward a rearticulation of the political, not as an independent domain but as a degree of intensity. Signs of this reorientation are evident in the second edition of The Concept of the Political published in 1932, and become conclusive in the largely ignored third edition of the following year. Already in the 1932 edition, the political emerges from Schmitt’s analysis as the field of antagonisms and antitheses— be they cultural, religious, or economic— once the polarisation they create is strong enough to divide groups of people into relationships of friendship and enmity. The friend-enemy distinction is consequently reframed as superior to every other possible one and, once a generative antagonism reaches the levels of intensity necessary for it, takes over all original disagreements and politicizes them:

The real friend-enemy grouping is existentially so strong and decisive that the nonpolitical antithesis, at precisely the moment at which it becomes political, pushes aside and subordinates its hitherto purely religious, purely economic, purely cultural criteria and motives to the conditions and conclusions of the political situation at hand. (The Concept of the Political 38)

This formulation marks a breakthrough in Schmitt’s critique as it posits the political against the prevailing liberal organisation of human thought and action in the form of autonomous, specialized domains. In contrast, the political appears here to exist as a potentiality, in a quasi-parasitic relationship with those spheres traditionally designated as ‘nonpolitical’, that is, the spheres of religion, economy, and culture. Being fundamentally constituted by its polemical intentions, Schmitt’s critique was primarily directed against the ideological principles of liberalism, as embodied in the laissez-faire character of the 19th century liberal state. Liberal thought, Schmitt claimed, provides the ideological space for the diminution of the political; it degrades “the political concept of battle” into “competition in the domain of economics and discussion in the intellectual realm” (The Concept of the Political 71). That is, through ideological operations Schmitt described as “neutralizations”, liberal thought facilitates the sublimation of political conflict into domains where the distinction between friend and enemy is obscured, or even appears no longer possible. The endgame of this trajectory is a non-political world, a world whose conflicts lack the existential dimension whereby political distinctions draw their legitimacy: the production of resilient political order.

Schmitt’s polemics against the depoliticizing character of liberalism are of course well-documented and often take centre stage in critical or affirmative evaluations of his work. What is, however, often overlooked are the far-reaching implications of his theory, which was not intended only to critique liberalism. Already in the first pages of The Concept of the Political, Schmitt anticipates the historical obsolescence of the liberal anti-interventionist state and its de facto replacement by a new form of political organisation, much more relevant to 20th century democracy: the total state. Although the Concept of the Political features the term undifferentiated, Schmitt’s later elaboration between its “qualitative” and “quantitative” types suggests that it is the latter which is of concern in the specific treatise. Whereas Schmitt conceives the qualitative total state as existing above society, from where it can monopolize the political - that is, it can exclusively control the distinction between friend and enemy - the quantitative total state “immerse[s] itself indiscriminately into every realm, into every sphere of human existence” (Schmitt, The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes: Meaning and Failure of a Political Symbol x). The quantitative total state, then, violently taking over the political vacuum of liberalism, repoliticizes all aspects of personal and collective life by facilitating the state’s complete penetration of the social:

What had been up to that point affairs of state become thereby social matters, and, vice versa, what had been purely social matters become affairs of state — as must necessarily occur in a democratically organized unit. Heretofore ostensibly neutral domains — religion, culture, education, the economy — then cease to be neutral in the sense that they do not pertain to state and to politics. As a polemical concept against such neutralizations and depoliticalizations of important domains appears the total state, which potentially embraces every domain. This results in the identity of state and society. In such a state, therefore, everything is at least potentially political, and in referring to the state it is no longer possible to assert for it a specifically political characteristic. (The Concept of the Political 22)

For Schmitt, consequently, the quantitative total state presents itself as a quasi-Weberian ideal type of state organisation in 20th century liberal democracy, and follows the erosion, or abolition, of the precarious distinctions that sustained the non-interventionist character of the liberal state of the 19th century. The quantitative total state marks thus the mass democratic subsumption of these domains in conditions of (liberal) political pluralism. In this environment, the prerogative over the political becomes the arena of conflict between multiple competing entities with comprehensive ideological-executive apparatuses. The newly institutionalized “rivalry between decisions” (Arditi and Valentine 40) presupposes the great expansion and diffusion of political relationships across the entire fabric of society and the simultaneous deflation of the state’s political character. As a cause and effect which collapse into one another, liberalism and the quantitative total state create, therefore, the conditions for what Derrida, in his critical reading of Schmitt, has described as “hyperpoliticization”: “The less politics there is, the more there is, the less enemies there are, the more there are” (Derrida 129). The “inversion and vertigo” of this proposition is the immediate effect of the constitutive logic organising the adversarial framing of the political: the unidentifiability of the structuring enemy unleashes a multiplicity of potential new ones (Derrida 84).

Through this act of “conjuration”, to continue with another term by Derrida, the subject of liberal democracy emerges hyperpolitcized and desubjectified. Caught up in sweeping processes of second-order politicization, the subject is able to recognize and represent itself only in relation to predetermined practices to which it passively gravitates and reproduces. This would amount, of course, to an extension of the occasionalism which Schmitt diagnosed in the subjectivity structure of liberalism already in 1916, in his Political Romanticism. Yet, in conditions of comprehensive colonisation of every social space by the political, the subject transcends this impassivity and submissiveness. It, now, finds itself consistently mobilized by perceptions of meaningful engagement with its surroundings in a public sphere oversaturated by small, meaningless and impactless political gestures which cannot— and are not designed to— effect the merest change, other than reproduce what Jean Baudrillard described as “the liberating claim of subjecthood” (Baudrillard 108). It is in this context that Bourriaud’s judgment on art’s inability to go beyond a politics of ‘display value’ should be understood. Through this, Bourriaud’s observation on the political affectations overtaking contemporary cultural production can move beyond the level of a facile, reactive disavowal and return to Althusser and his theory of interpellation in the ideological production of the subject.

READ PART 1 HERE

READ PART 3 HERE

NOTE: This article is the ‘Author Original’ (AO) - the final ‘Version of Record’ (VoR) was published in Angelaki: Journal of Theoretical Humanities, Vol. 28, Issue 5

CITATIONS

[7] Robert Pfaller, On the Pleasure Principle in Culture: Illusions Without Owners (London: Verso, 2014).

[8] See Leo Strauss, Notes on Carl Schmitt, 101-103

As Heinrich Meier has documented, it can be demonstrated that Schmitt amended his original formulation which posited the relative autonomy of the domains of the moral, aesthetic, and economic, and, more importantly, the political’s analogous relationship to those, spurred by Leo Strauss’s critique. Traces of this reassessment survive in the ambiguity whereby these problems are treated in the 1932 edition of The Concept of the Political. For instance, page 26 of George Schwab’s expanded edition of 2007 presents the political as “independent” but not as a “distinct new domain”, whereas in page 38, the concept of the political no longer “describe[s] its own substance, but only the intensity of an association or dissociation of human beings whose motives can be religious, national (in the ethnic or cultural sense), economic, or of another kind.”For a comprehensive discussion on the relationship between the two men see: Heinrich Meier (ed.), Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss: The Hidden Dialogue, trans. J. Harvey Lomax (Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 1995)

[9] Schmitt clarifies this distinction between quantitative and qualitative total state in “Die Wendung zum Totalen Staat” (1931), “Weiterentwicklung des Totalen Staates in Deutschland” (1933) and "Starker Staat und Gesunde Wirtschaft" (1933).

[10] The confluence of quantitative total state and liberal democracy may come off as a surprise, but it should be remembered that Schmitt’s own analysis was based on the Weimar Republic. It was Schmitt’s conviction that the hybridisation of the democratic identity between governed-governing with principles of liberal pluralism creates the conditions for the colonisation of society by “indirect powers”, that is, social organisations and interest groups which can enjoy the benefits of governing without any of its responsibilities. This new political environment subverted the Hobbesian balance between obedience and protection which Schmitt considered to be the core of political order.

See Carl Schmitt, The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes: Meaning and Failure of a Political Symbol, trans. George Schwab and Erna Hilfstein, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996

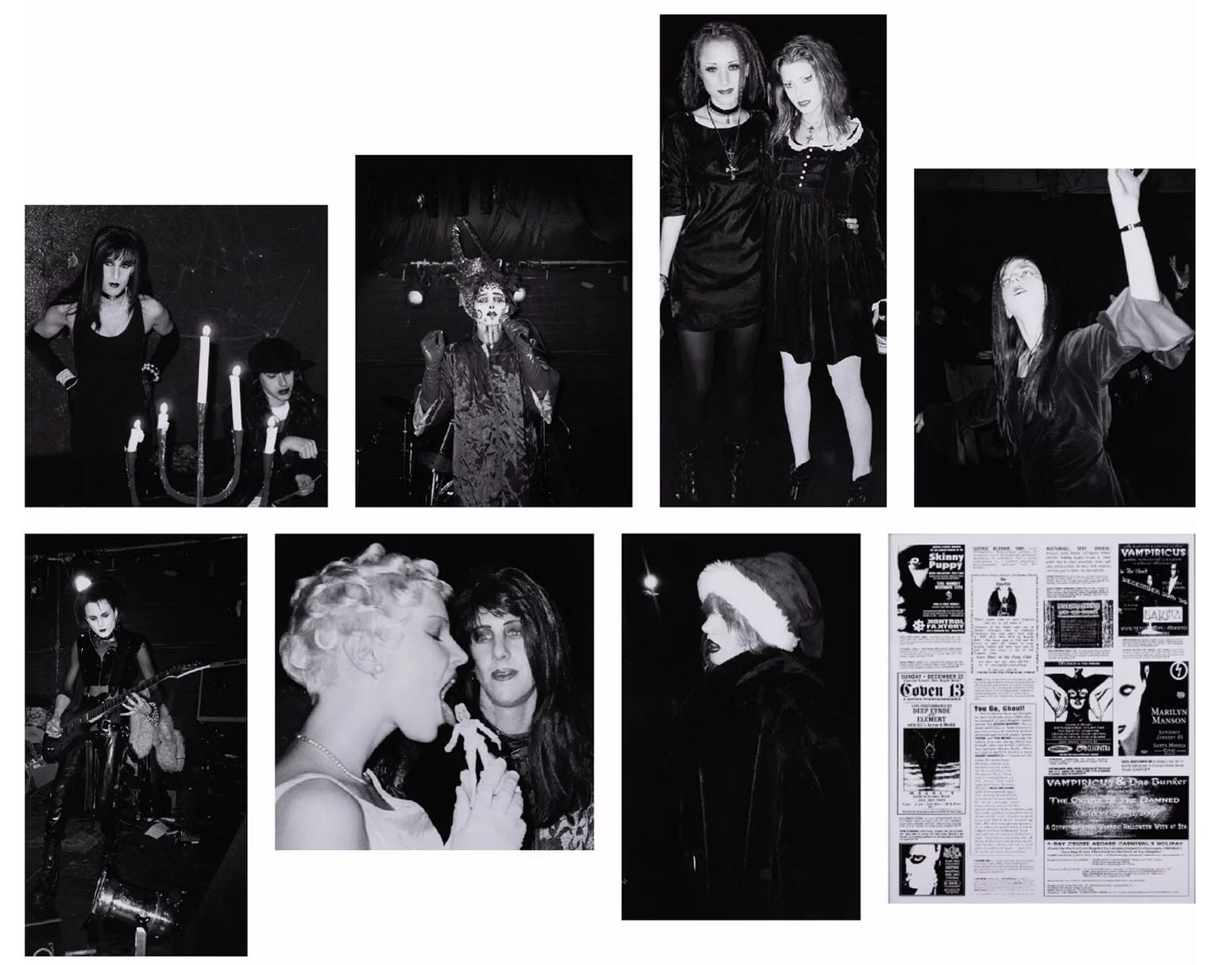

Illustration by Mike Kelley and Cameron Jamie