Instances of Crypto-Transgression #8: On 'The Apprentice' and Portraiture, Part 1, by Adam Lehrer

In the first part of this two part film analysis, Adam discusses Ali Abbasi's Trump biopic and finds in it a perhaps accidentally flattering portrait

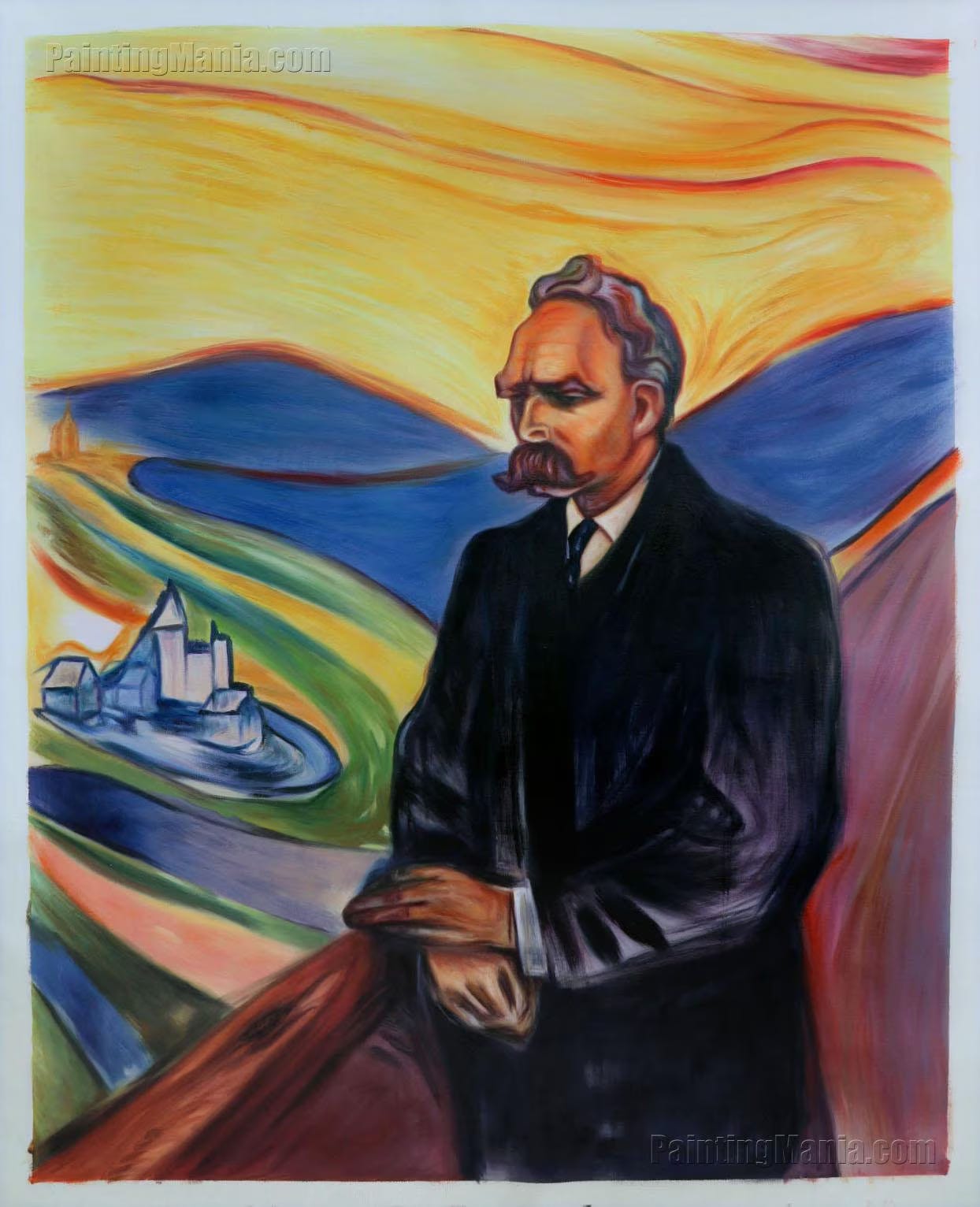

When I paint a person, his enemies always find the portrait a good likeness — Edvard Munch

Portraiture, even if intended to damage its subjects or portray them in an unflattering light, always exalts its subjects nonetheless. As grim an image as it is and as fraught as Francis Bacon’s relationship with Catholicism might have been, there’s no denial that Bacon’s Study after Velasquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X is an incredibly potent distortion of the flattering portrait painted by Diego Velasquez of Pope Innocent X in 1650. While the painting obviously reflects Bacon’s personal disgust towards the papacy, it also accidentally depicts the undeniably dense aura that the power of the pope evokes. Thus, the artwork reflects emotions to the audience that might be entirely unbeknownst to the artist himself. The artist paints the portrait with his own biases, but few if any of those biases will actually be shared by the audience who will impart their own beliefs onto what they see. If Catholic, perhaps you regard Bacon himself with disgust for even attempting to undo the majesty and pageantry of the Catholic Church. Or, maybe you simply see something in the painting that Bacon did not; a macabre worship of the church’s power, perhaps?

A portrait, you see, has a life of its own beyond the artist and beyond the subject. While it’s true, like Oscar Wilde said, that every portrait is in actuality a portrait of the artist, it is also a self-sustaining story of the subject that is utterly open to audience interpretation. A condensed space of both discourse AND biography. One will see in the portrait what wants to believe about the subject being depicted. Edvard Munch knew this, and understood that his dark, menacing portraits might be appreciated by his subject’s “enemies.” He might not have realized that those portraits also might be appreciated by his subject’s friends. People see what they want to see when a depiction of reality, even a depiction of reality imprinted with an artist’s subjectivity, is reflected towards them.

I have no clue if Iranian-Danish filmmaker Ali Abbasi meant for his Donald Trump biopic The Apprentice to be a flattering portrait of the newly minted President Elect or not. Nevertheless, watching the film from my perspective, a perspective shared by over 70 million people to varying degrees (as evidenced by last week’s election), a flattering portrait is exactly what it is, or at least can be interpreted as. Perhaps going against the filmmaker’s own political instincts, the movie is totally enamored with Trump’s monumental charisma, seismic ambition, and Queens-bred New York eccentricities. It is, largely accidentally I would assume, just about the most positive rendering of Donald J. Trump put to celluloid that anything the modern film industry would ever be able to put out, and certainly more so than any American filmmaker subjected to Hollywood ideological screenings would ever be allowed to make.

Trump is obviously not happy about the film, calling it a “cheap, defamatory and disgusting political hatch job.” And certainly, there are defamatory aspects to the film. Trump, as much as I adore the man, doesn’t have much levity when it comes to depictions of him. According to JD Vance himself, Trump doesn’t even enjoy Shane Gillis’ obviously loving impression of the man. And for him, I understand that in The Apprentice he sees a movie that makes fun of his male pattern baldness, his brief amphetamine habit that caused episodes of erectile dysfunction (come on, everyone has had episodes of erectile dysfunction it’s not THAT BIG a deal) and his contempt for people stealing his limelight in any regard. But these things are also all true, so offensive or not, they’re hardly defamatory.

There is only one sequence in the film that I would describe as actually defamatory: Abbasi’s decision to depict the violent domestic dispute that transpired between Trump and ex-wife Ivana Trump in the late eighties, alleged by Ivana in a sworn deposition, as an outright violent rape. Ivana later clarified her usage of the term rape:

"As a woman, I felt violated, as the love and tenderness which he normally exhibited toward me, was absent,” said Ivana. “I referred to this as a 'rape,' but I do not want my words to be interpreted in a literal or criminal sense.”

What Ivana is saying here is, obviously, that Trump didn’t actually rape her, but that they had a difficult and perhaps ugly sexual experience where he acted out of character. You can also sense that she was deeply hurt by his infidelity, but the details of the encounter are far too shadowy to impart total judgment onto.

Abbasi, or his producers, seemingly couldn’t help themselves, and decided to show the scene as a violent rape. The scene is awkward because it seems completely out of character not just for who Trump actually is but who he’s portrayed as being in the film. I’m sure there was a domestic dispute, but it feels like the choice to show Trump at his worst moment is some kind of concession made by Abbasi to the producers to get it made. The scene’s depiction of Donald contrasts so sharply with how he’s shown in the rest of the film that it actually becomes quite hard to believe, and makes it easier for the audience to disregard it all together. Coincidentally, the scene is a bit “edgelord,-y” almost suggesting an encrypted criticism of the libtards who would so easily lap it up and use it as more fuel fanning the flames of their terminal Trump Derangement Syndrome.

Despite all these negative criticisms of its subject, the movie puts deep emphasis on the near surreal magnetism of Trump. Sebastian Stan’s portrayal of the 45th and 47th President of the United States is extremely layered, dedicated, and not at all condemnatory. To say it’s the performance of the year is a huge understatement. It’s one of the best leading male roles of the decade. Stan decimates one-dimensional caricature to unearth the humanity of the most towering figure of our lifetime. You couldn’t ask for a harder role to play, and Stan couldn’t have nailed it any harder. It’s a piece of performance art that surpasses masterpiece.

To play Trump effectively, Stan seems to know that he had to tap into the aspects of his subject’s personae that are so deeply appealing to the masses. Stan manages to evoke Trump’s toughness, strange mannerisms, and even his sweet naivety, a quality that the media has always pretended to not see but can be seen so clearly by Trump's huge base of supporters. In one scene, Trump shows his beloved Scottish mother Mary Anne Macleod Trump — Trump was a total mama’s boy in the way that great men often are (Alexander the Great, Emperor Heliogabalus, Genghis Khan, George Washington, John Quincy Adams, and on and on were all certifiable mama’s boys) — a cover story of him in New York Magazine and sweetly humble brags:

“They even called me controversial” while his mom assures him he did a good job, proud of the man her son has become.

Basically, Abbasi applies a kind of ideologically mute portraiture aesthetic to its subject matter and, probably falsely, assumes that the audience will see its subject, Trump, as evil. But again, this is the beauty of portraiture. By reflecting reality strictly, you manage to evoke so many more ideas than you do working with art conceptually. I’m reminded of the Dutch art collective KIRAC’s documentary on controversial art collector Stefan Simchowitz, where the filmmakers perhaps assume the subject’s bad taste and manners but through all the honesty end up making Simchowitz seem fucking awesome.

“Stefan Simchowitz turns out to be a force to be reckoned with, an antagonist who both seduces and disappoints,” writes one of KIRAC’s artists Kate Sinha on the film. “The film is an intimate portrait of an extraordinary man who has the rare talent of truly believing in himself.”

In the 19th episode of KIRAC’s evolving film series, Sinha elaborates upon the rebellion of portraiture against the grain of the bland agitprop liberal shilling that has come to define the prestigious cultural industries — visual, film, literary and otherwise — since the 2010s at least and, in all reality, since postmodern art centered itself around the concept of “identity” in the 1980s (typical art discourse of the 1980s: was Cindy Sherman’s use of black face in her self-portraiture racially insensitive? Or was it a conscious critique of the ills of racism? Point is, this shit has been going on for a long time and was always bound to just get worse and worse):

“A portrait is completely at odds with the kind of art you see in the tasteful global sphere,” says Sinha in a stirring monologue. “A sphere that deals with socio-political themes. A sphere that assures the elite that they are aware of the important things in the world.”

The quotes above are extremely pertinent here on multiple levels.

For one, The Apprentice itself rebels against the tasteful global sphere of arthouse cinema by reveling in portraiture, which innately shuns socio-political grandstanding in favor of a hardboiled look at reality. Realness, and authenticity, are what elevates portraiture above other arts and, coincidentally, what distinguishes Trump from his enemies. On an even deeper level, however, the film is also a portrait of an elite man, but THE elite man who has single handedly shown the liberal elite just how out of touch they are with what ordinary people actually care about not just once, but twice now.

Trump is the class traitor who exposed the mass delusions of his own class and the institutions of that class. While It might be a bit of a cliché to say as much now, Trump really is our Caesar; the aristocrat who channels the discontent of the people and weaponizes it against the ruling elite because the elite despises him and wants to control him just as much as is despises and wants to control us. There’s no way to accurately depict Trump, which the film does, without highlighting the attributes that make him a symbol of rebelliousness. Of strength. Of resilience. Because Trump is so innately authentic in a manner that perhaps no politician has ever been, this film becomes a stirring portrait of a gangster, sure, but also demonstrates that it takes a gangster with values to overcome a bureaucracy as evil as the one that the Democratic Party apparatus had become.

IMAGES

Sebastian Stan and Jeremy Strong in The Apprentice

Francis Bacon Study after Velasquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X

Munch’s portrait of Nietzsche

Read part 2 here