THOUGHTS: 'The Substance' and Aging Starlet Hags

Coralie Fargeat's 'The Substance' presents a feminist body horror being honest with itself

When I first read the buzz around French feminist filmmaker Coralie Fargeat’s new Demi Moore starring body horror film depicting the horror of the starlet aging process — unanimous praise from the likes of Owen Gleiberman or Indiewire is a surefire way to guarantee my absence of enthusiasm — I thought: “Oh god, here we go, another feminist libtard having a stab at the material Cronenberg made his territory in the 1980s.”

After all, it was Cannes who gave Julie Ducournau a Palme D’Or for the absolutely dreadful Titane, a film that clearly referenced Cronenberg’s adaptation of Ballard’s Crash but did so in the most ponderous, vacant, and transgender signaling of manners. Truly, I still have no idea what that film was other than “trannies”. Trannies is all that it evokes.

Cannes lost its relevance long before this, but the elevation of THAT film signified the desperation with which the most prestigious prize in global art house film was trying to prove that FEMALE FILMMAKERS MATTER.

Since then, the Cronenbergian feminist body horror film has become a perpetual mode for young female burgeoning filmmakers. It makes sense in some ways. Catherine Breillat, the greatest and most intelligent of all female filmmakers, cites Cronenberg as an aesthetic ally:

“[Cronenberg] was trying to challenge and change the aesthetic codes around the representation of sex,” says Breillat in Senses of Cinema. “When you look at organic objects, such as sexualized bodies, you are filled with shame and fright. Once you are used to it, there is no shame or fear to experience, so you’ve changed the aesthetic codes and from that you actually create a new gauge for morality.”

Morality. Breillat has described herself as a puritan, which she says makes it all the more thrilling to create such sexually charged moments. I assume Cronenberg feels similarly. Both artists agree upon a universal morality that they can identify, subvert and perhaps even challenge through their aesthetics. It makes perfect sense that millennial filmmakers, who are innately obsessed with being women, being sexualized, and having bodies, would hold such reverence for artists like Cronenberg and Breillat.

The problem is that millennial women do not have an agreed upon morality from which to subvert. Instead, they only know art as fashion. As an image to be posted on social media. As a sequence of images to define their Tumblr aesthetics by. This empty Cronenberg/Breillat reference has become a cancer of contemporary film art. We can chalk pieces of trash like True Detective: Night Country, Rose Glass’s Love Lies Bleeding, the wretched new film (and novel of the same name) Night Bitch, Arkasha Stevenson’s The First Omen and the aforementioned Ducournau, the most critically acclaimed of all of these names, up to this aesthetic plight.

My first assumption about The Substance when I read about its warm Cannes reception and its body horrific themes is that it would stand amongst this heinous glut of recent feminist body horror. Then, Jack Mason of the Perfume Nationalist bucked my expectations by voicing his enthusiasm for the film:

“I realized it was great,” said Jack. “It's almost post-feminist the way it revels in a version of the female experience from about 1988: “Eating is bad, women get old and become worthless, everyone wants to be young and cute and adored. It communicates in broad archetypes and icons, the type that midwits have been taught are stereotypes to be avoided, and this is the source of its freshness and power.”

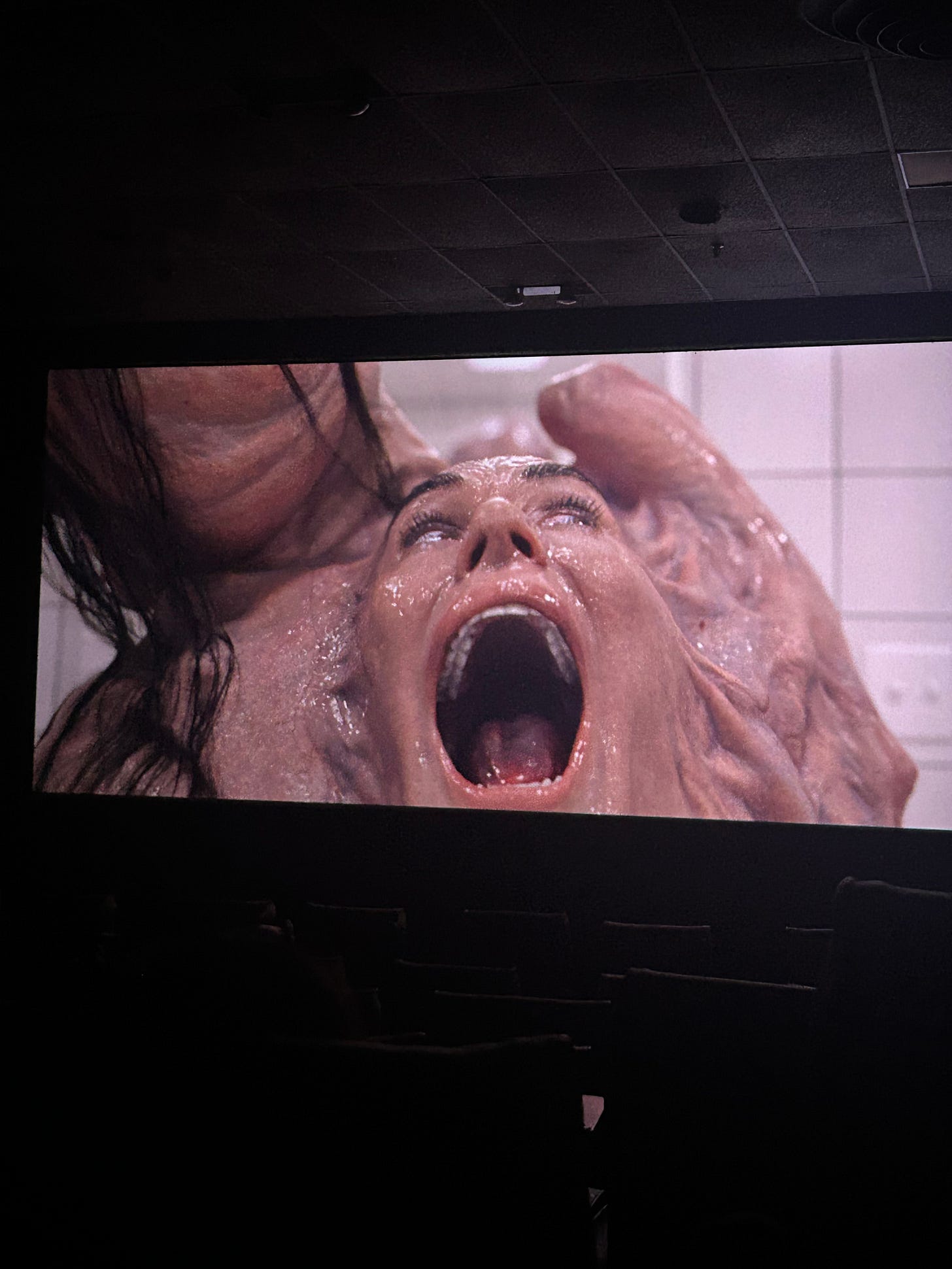

I did some research. Fargeat’s last film was Revenge, a rape revenge thriller of the I Spit on Your Grave modality but clearly stylistically influenced by horror classics of the New French Extremity like Martyrs and High Tension, which managed to completely adhere to its genre’s tropes without feeling weighed down by them. The narrative of the film and its revenge plot is extremely far fetched, but Fargeat defies logic and reality to create a greater philosophical point about the female obsession with both being raped and avenging that rape. It’s a film that functions in the cathartic manner that films of this kind often do, but also offers greater inquiry into feminine dysfunction and spite.

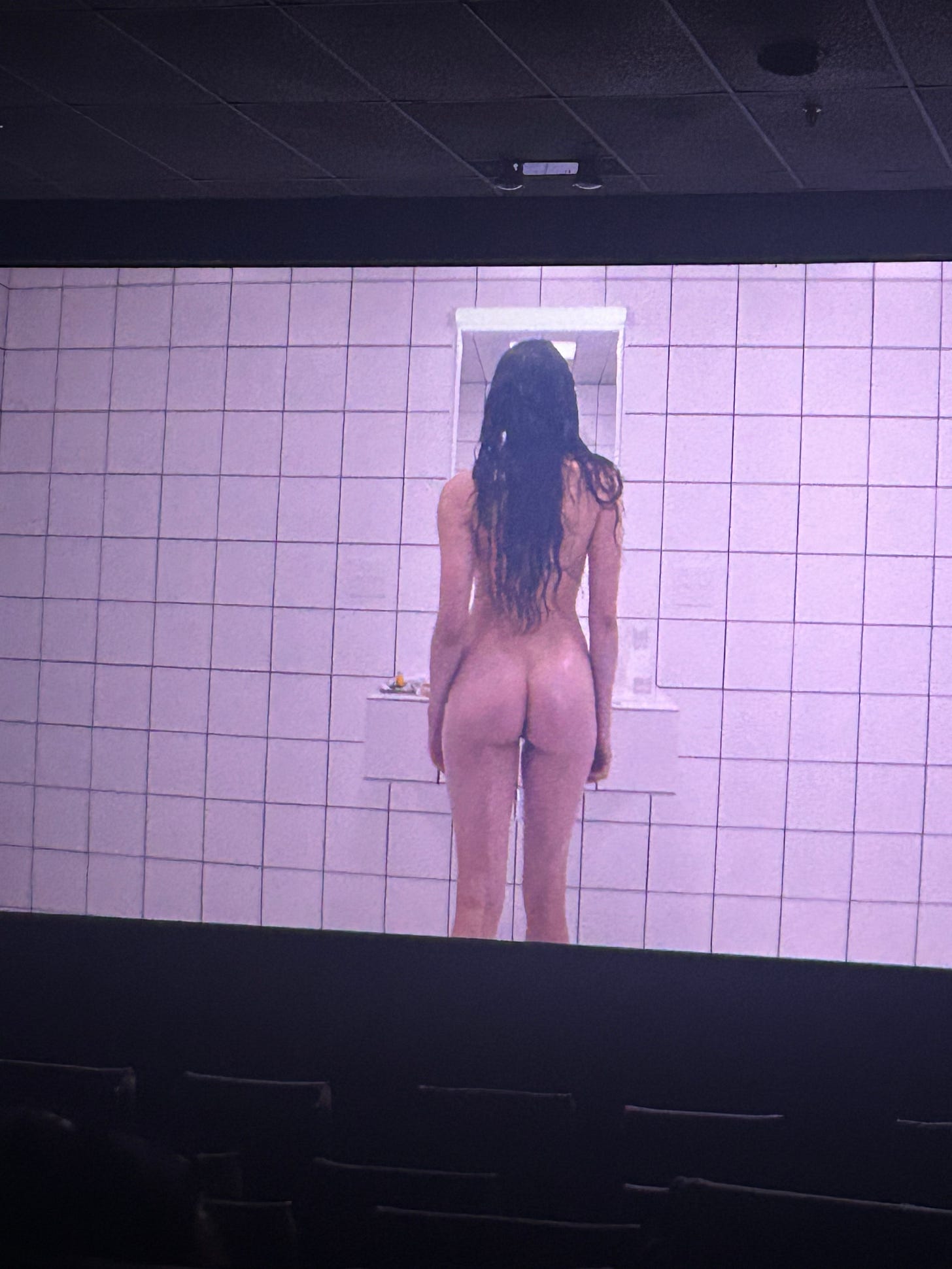

Her protagonist in Revenge, curiously, isn’t the completely innocent victim that we are used to seeing in the rape revenge genre, but instead is the kind of woman who fucks a married man and puts herself in highly dangerous situations. Upon rewatching, it’s clear that Fargeat has questions about women and society that very few women artists are willing to wade into. She also uses very, very hot actresses. Italian actress Madalie Lutz is insanely fuckable in Revenge, and Margaret Qualley looks like a pink pussy goddess in The Substance.