Three Texts on Tarot, by Brad Kelly

Writer of fiction and host of the Art of Darkness podcast Brad Kelly GETS Tarot

Eight of Pentacles

The pentacles speak, at one level, of what can be touched and seen, heard and smelled. The Earth and all that lay visible upon it. Now, see your body? See it as a thing that belongs to you if nothing else. And see that as a metaphor for any project you might undertake with it. The running of a marathon, the writing of a book, the careful beading of a long and resplendent gown.

The figure in the Eight is an artisan working out at the edge of the town. Six of his coins already chiseled into shape. One on his bench and another another at his feet, discarded as inadequate, as requiring a few more steady-handed hours. To the untrained eye, each coin is identical, but for the craftsman himself, each must be its own novel, its own ark, its own story and trust that he found a dozen morals taking it from blank to symbol.

---

In Africa, there were once men—slow and vulnerable, without fang or claw—who would kill a single antelope over the course of hours. They’d spook the creature from its herd and one hunter would give chase across the flats. An antelope, of course, can out-run a man in any foot-race except, here we learn, the longest. And so the antelope will sprint to safety and the man will follow behind, pacing himself for anticipated miles. The antelope will tire and rest on the ground until the man comes near and then run again in an efflorescence of adrenaline, the ground covered a little shorter than the last. Rest again until the man approaches spear in hand. Repeated: the man ceaseless, barely out of breath, the antelope ebbing and grinding away until it lays down and cannot summon the energy to stand again. The killing then, the final punctuation, is no more difficult than plunging a shovel into the dirt.

---

After an interruption of several years to drink too much and carry-on with friends into the wee hours, I have worked my body into fitness on more days than I have not. Fifteen years now. Maybe more. A half-million pull-ups, at least. Countless moments finding my grip in the knurling. Until my default posture has come to be either crouched above the keyboard or bent over my knees catching my breath.

And in all of this, there was no one dragging, sweating routine in the gym that made any difference you could see or measure. There was no day in which I looked any different than the day before. And so the enterprise carried-out on the faith that if submitted to today—and tomorrow and a month from now still, a year—the discomfort and time would be worth it. That you could chip away at the stone one flaking gouge at a time—and some day before you would sit a sculpture you could scarcely imagine when you began.

---

It’s within your birthright to do one impossible thing. Perhaps your father let his own expire. And his father before him. But if you were to find your project and lean into it—Sisyphus, smiling—you might, over years, top your summit. There is only one way to find out. We’ve filled the Earth with examples. Every memorable book you’ve read, every great album and film and invention. In each of these, the creator spent the time. They chipped away, a sliver closer at nightfall than they were at dawn countless times over.

Pentacles are knowledge, too, skills that can be honed from the crudest talent. And they are Money, says the RenFest psychic. And money grows, tended to correctly, laid open to the almost biological processes we’ve created for them—a mirror or something we feel about the workings of the world. Think of the stacking mathematics of an interest-bearing account, on it compounding every day and slipping a little in those that go by idle. Every day a little more and the next day’s push on that rock from a higher fulcrum, the weight a little closer to it. Where will you be a year hence. A decade from now you’ll be interplanetary, sending images of dimly-known planets back to your former self on earth. For now, sit on the bench. Feel the cutting weight of the chisel, test the heft of the hammer, see how clear and vulnerable is that blank and how long must you chase until it submits.

---

I wanted to be cut like Mr. Universe and as famous as Stephen King. I put in nowhere near the work necessary for the first and enough but in the wrong direction for the latter. It’s all okay. The Earth is the safest of the four. Look at the craftsman’s face. Not smug and not simply bearing the work, nor grim, nor suffering. He looks not at the work he’s done but at that in the doing. This is what we learn from the Earth: what glory is to be found—a glory of the hardest knock, the lowest center-of-gravity—is in the fraction of a percent between a second ago and right now. In the slowly swelling mastery that you can feel like gravel under your boots, like calluses on your hands. Perhaps one day there will be time to pause and reflect, to cash in and see what lucre or fame might be awarded. But they’ve little to do with right now.

You carve the line deep and true. And when it’s reach reached its vertex, you turn the tablet and you set the chisel. You squint your eyes and you purse your lips and with that hammer, the handle worn smooth in your practiced hand, you give a little whack. You watch the first flake curl and fall to the ground.

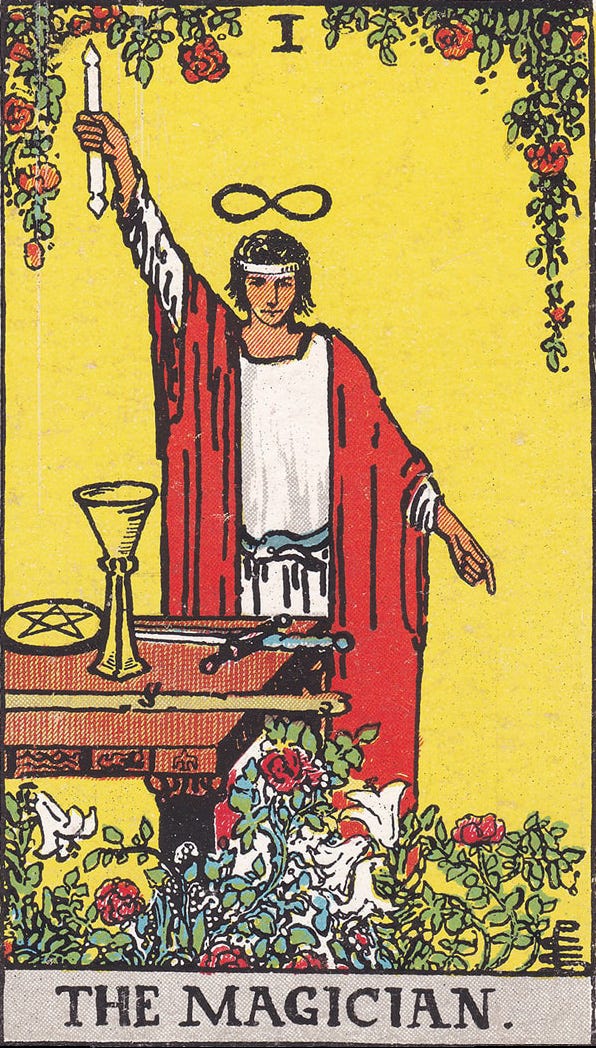

The Magician

There was a moment that is not in your memories, try as you might, where you first had a thought and that thought led through tears to the thing you wanted being yours. Your first trick and the forever most fascinating. A lifetime spent learning its intricacies. Not the tears themselves so much as the pledge and the turn and the prestige.

The Magician is a card of Will. A locus of debates as old as those around God, and one side says of course there is free will, gifted to us by the same, and the other that it is an illusion. That we are chemical reactions calculable down to the blink. But see the Magician: he is an agent without doubt, and a symbol of our first preening tears for milk and our final prayers for salvation. And he holds his wand an arrow-straight antenna to focus the lightning. The lightning not from him, of course, but channeled through his Will. What a paltry notion, that to be a conduit makes us somehow less.

---

For years, I thought I chose. Writing since I barely could—fiction always, from comic books to short stories to weird little beatnik screeds—I assumed there was some rational cogitation to it all. They call it the Age of Reason because it’s in those years you’re convinced it all makes sense even if you cannot see the pattern yet. When I had a year or two left of Engineering school—not sure I chose that either—I was kicking through rain puddles thinking how would I get to this book I wanted to write with all the studying and the work and the partying into the wee hours. A compromise came to light: I would do what I could now and not fret, and then once they handed me this diploma I would change my life such that there would be time. I would focus my efforts. I would study and I would practice and I would learn. I would transfigure myself—an alchemical process—into a writer. There was no cost-benefit analysis. There was no ROI. This was bargaining with the lightning that I would find a way to run it through to the ground.

---

In the memory below your memory is a fogged-in glade, is a hollow in the land where you hid and plotted for calories. And in that place you marveled at a stick that’d fallen onto your mat, under whose possession you’d fallen. And you held it, grunting to some other cowering member of your band. And later you wielded that stick to lever termites from their home, to crack a thin flat bone, to trench through the dirt for a precious rock.

Perhaps this was the first analogy. As good a guess as any. Your second magic trick and the whole history of your race flowing from its tip. A wand is a stick, nothing less. And it is, too, an arm, a finger, a fist. And a fire is a stomach, the sky is a father. A few grunted phonemes is a rock, a baby. A lightbulb is an idea.

---

Five or six years later, I’d written a couple stories that got me invited to one of a few Meccas for us young writers. The MFA a seeming portal to Vallhalla with which we were rewarded to live our next life if the last was executed with bravery. And there was this rendezvous point, an old house at the edge of campus where some famous writer had lived, where we sat up to three times a week to talk books and writing and in-between I read those books and I did that writing and though my bills were all barely covered I was as rich as I will ever be.

While there, I wrote a book you will never read. And I read books I’d have never read if I hadn’t gone. But the most important work, it would turn out, was not quite either of these: Down from the rendezvous point, across the creek, off the backside of a little-used park, I’d found a bamboo grove someone had planted years before. Every chance I got, I would slip off twenty paces into these strange trees until I was sure I was invisible. And there I’d sit and write in my notebook and smoke a modest smoke while I listened to Ram Dass talks on my phone.

Ram Dass talked about the curriculum. About how life is a school and so you might as well learn the lessons. And the curriculum is yours alone, as much as it might be like your brother’s or your neighbor’s. You are here, he said, to learn something that maybe only you can see and you’ll learn that thing, only, by doing what you are intended to do.

And I was looking at some sentence I’d written that I thought was good. Good enough, maybe, to be worth halting my day-job career prospects and moving cross-country and all of it. Maybe the sentence wasn’t good. It doesn’t matter. The sentence itself...I did not remember writing it and read it there like some message from a future self found in a matchbox buried among the bamboo. To me it meant that I could do this. That I was a writer as I’d promised myself I would become. That I could craft a sentence and then a paragraph and then a story that would float in the reader’s head—if even just one of them. That I could get an idea—and not just that, but a feeling and perspective—out onto paper, make a mental construct real such that it would breathe and sleep and eat like a crude little creature. And I was seeing now—exhale, look around for witnesses—that my curriculum was, in fact, to write novels. That I could craft a little radio out of coconuts to pick up the faintest of signals and turn that message into a map that might guide my shoddy raft home. Quite the magic trick.

---

A pyschotechnology is when some function of how the mind works is leveraged and amplified, perhaps carried over into another context in which it might be useful. And so, Brunelleschi forced the human eye into paintings, and the Buddha saw that attachment is the cause of suffering, and Liebniz understood that the human clamor for yes/no can be a coding system from which all others would be grown like beans.

Of late, we’ve come to understand this concept of Flow. It was right there in the first major arcanum all this time—the Magician at his electrified ease—but we needed an academic to write a book. Flow is that moment when we’re engaged, almost trance-like, in our activity—and not just any, but the ones for which we’re programmed. Or destined, take your pick. And when the Flow comes, the task unfolds without any seeming effort and time passes untracked. You can hardly make mistakes and you ride each move as much as steer them. A concentration beyond concentration, a momentary hardening of the self from the flapping and jostling thing that you are to the smallest pinpoint of attention that can bear the weight of everything that you know.

---

In a moment of darkness long years, but not many, after that bamboo grove—it had all failed, nothing I’d built had toddled further than a few steps, though I still wrote every day—I sat cross-legged and sleepless on the floor of a spare room I couldn’t pay for, half-employed and half-lonely. Feeling older than I feel even now.

And so I laid down some cards. The question: “What do You want from me?” and among that mosaic response this fiery man in his flowing robes, the table before him a scatter of mystic tools. A humble question—behind it the motivation to submit, to continue the curriculum if only I could make some sense of it. And so what’s this card mean laying there at the root of the spread—a million readings and a million meanings all shades of the same.

It said, have you not been whittling and shaping that wand these years since the rain puddle. And have you not been hardening it in the flame. And haven’t you come through all of it with at least your wits. Maybe that means something to you as well, I hope it does. And it said you don’t get to be some other person and sit in some other class no matter how much you squirm and misbehave. And it said you better strap that ouroboros about your waist and stand before your table, the tools may be meager but this is a promise that they’re enough. And it said, now grit your teeth and plant your feet, close your eyes and point to the sky. It said that the only way out of this is to bear the lightning that is meant for you.

Knight of Swords

The knight fights for king and country. For god maybe. And yet a myth sustains him, an old story true from time to time and why not for him: that he might, like kings of old, fight his way through vainglorious triumph to sit squarely on the throne. That is, we should see the knight as caught up in the struggle required to seize the kingdom. No ruling here, except for ourselves. And for the court of Swords this means to be become the master of the thinking mind, a paradigm of intellect and ethics, of analysis and rational justice. One who can cut through the bull to the truth. To win this long war is to become the wise consultant who might solve any problem, the more technical the better.

+ + +

There were a million dragons in my youth—the nearest at hand in the shape of a vaulted cathedral, its craning neck a steeple, its scant plumage stained glass saints. We were Roman Catholics, with every weekend a dirgeful ritual and each holiday an obligation. Well, I thought I was too smart for all that God-bothering. I trusted the microscope and the caliper, the brute force analysis, the sharp end of mathematics. I couldn’t believe a thinking mind would be deceived by simple incense and oratory, by tradition and hymn. I thought my blade, a dragonslayer now, was sharp as the hyaline edge of obsidian.

+ + +

Knights are the teenagers of the court. Energetic and idealistic, willing to sacrifice because they don’t know what they’re putting on the line. And so they can be stunningly brave, for sure, and reckless. They can hold the principle they’ve learned with an unbreakable grip, and they can bludgeon the world with the letter of the law—understanding nothing of its spirit. It’s a card about running the meridian between a virtue and its dark twin: direct to one side and tactless to the other, incisive versus derogatory, knowledgeable versus knowing-it-all, authoritative or authoritarian. This balance has to be learned one way or another. . .the way children come to understand through rough and tumble play and falling out of trees. The way one becomes a master of a thing by being painfully inept at it for a long, long time.

+ + +

The collective thought is spangled and dripping with theories on how life originated: trickster gods and immaculate sculptors and lightning strikes on fetid pond scum. None of it is satisfactory to a cutting mind. For a scientist, the irreducible granule of life is that which replicates itself. A man named Graham Cairns-Smith posited, in the 1960s, a starting point, a dim echo, of the self-doubling pattern that makes us alive. He said that, before DNA could weave and unweave and copy itself, the magic of re-creation played out in the humble dirt. Clay crystals—of course, not at all what Jehovah rolled into Adam—may have propagated their defects and perfections, may have been shaped and selected for by the peculiarities of water and sun and gravity. Crystals grow, they do, they self-assemble, they pass along their imprint to their sons and daughters, look it up. They alter as well, they shift and reform and adapt. Cairns-Smith said these clay crystals gathered—over some eon eons ago—the nucleotides and proteins that are the wires and transistors of the robot that is us. And then this biological material, aggregated and recapitulated, eventually left behind the clay, the organism left behind the dirt. And yet without this dim-witted bridge, not a thought in its head. . .well, then you have nothing that can breathe or think.

+ + +

It took a long time to realize that my next dragon was rationality. I’d let it swallow me whole, assuming I’d be warm and safe inside. And yet, how cramped my quarters were, how little I could see. But I let that dragon fight for me, scorching all the dark goblins of the land, the petty thieves. There are plenty of those, of course. And yet it’s a countryside not only beset by delusions but graced by mystics and clairvoyants, poets and seers. They too were burned and I became no wiser.

This is not the card that tells you how the switch was made. How one climbs out and turns this dragon into a pet—pull an ear for the flames, pull the other to take flight. But it came to be my servant, Reason did, even if I cannot always tell it what to do. It’d be far less powerful if I could. And I can see now, as I look back across the wasteland—the scorched earth and the oases we found in our wanderings—that none of it would have come to be had I not put that first monster to sleep. Much respect and honor on its name, but freeing myself from its grip—yeah, that’s the ticket—loosed me into a vertiginous freedom. To think. To further sharpen my blade. I’ve left behind the humble dirt but will always revere its name, carry a little of it in a jar around on my neck. On to the throne. It is such a long and harrowing way.

Brad Kelly is a writer of novels, short stories, and explications/refractions of the Tarot. He is the co-host of the podcast Art of Darkness—featuring conversational profiles that focus on the dark side of creativity through the lives of great artists. He is a former Michener Fellow and has been widely published in literary magazines. Follow him on Twitter at @bradkelly