Visual Propaganda #5: Alexander Lebedev-Frontov

Dedicated to the visual art of Russian artist, industrial musician, and former party member of the National-Bolshevik party Alexander Lebedev-Frontov

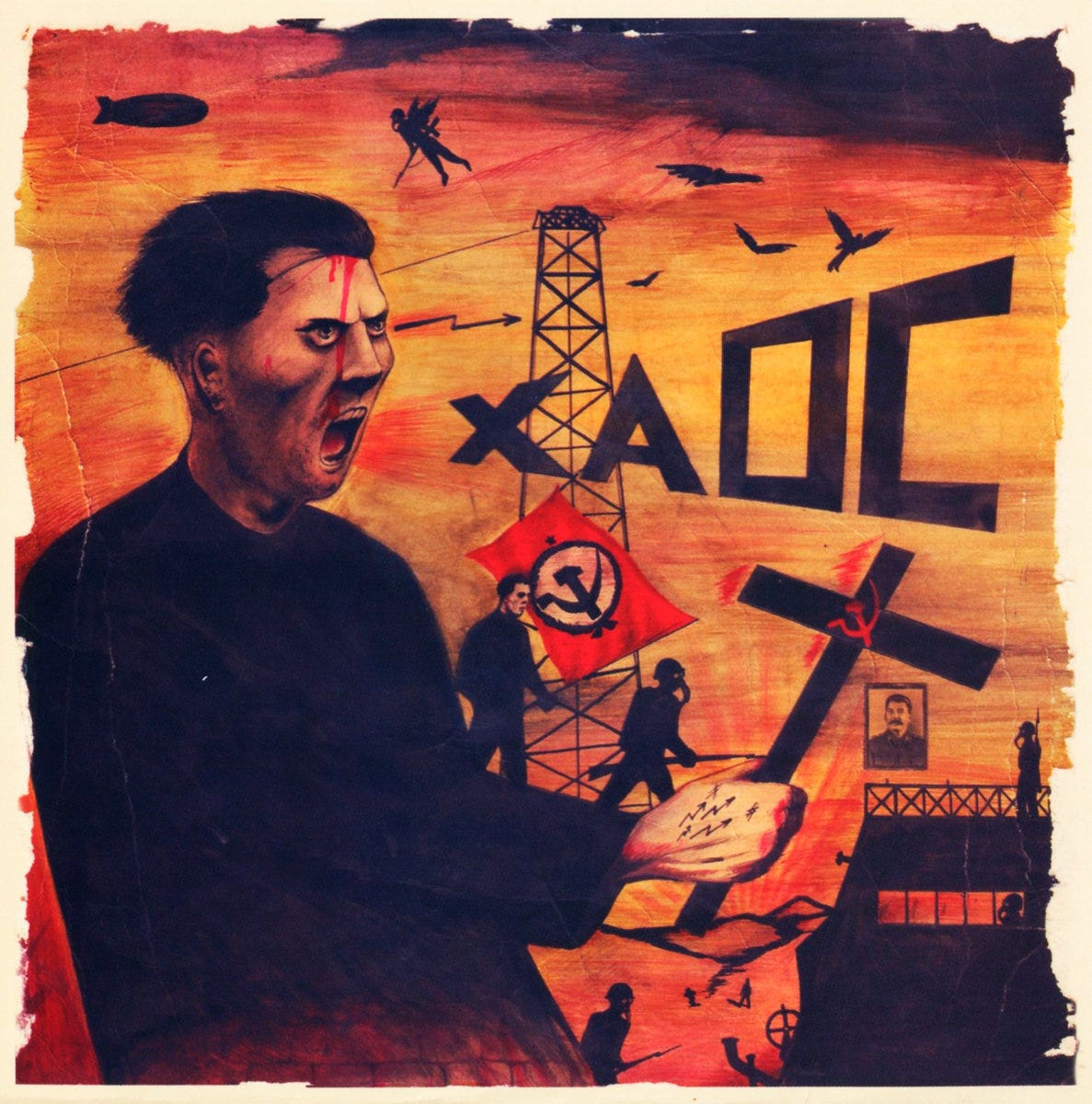

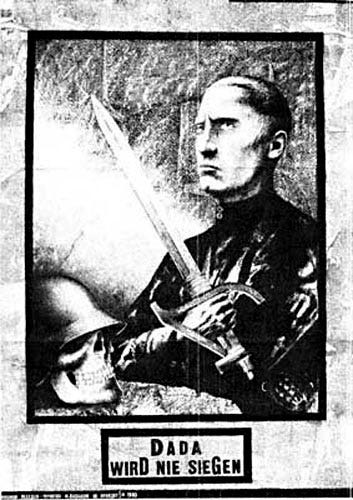

“Visual Propaganda” is typically meant to be understood as tongue-in-cheek when it comes to this column. For this time though, read the phrase with utmost sincerity. Alexander Lebedev-Frontov is many things. The Russian polymath is best known for his work in industrial and noise music and partly pioneered the emergence of a subterranean avant-garde music scene in Russia in the late 1980s and 1990s. Recording under names such as the harsh industrial leaning Linija Mass, his best known project, as well as the more blistering noise of Veprisuicida and Vetrophonia, a dark ambient project, Lebedev-Frontov makes an exceptionally dense, harsh, and layered industrial racket that proves difficult listening even for mine own well-worn, pretentious ears to weather. For a period during the 1990s, he was a figure of controversy for his stated political commitments. Now typically, of course, outwardly political art can leave you with a lingering nausea for its reductive ideas or implied allegiance to multicultural liberalism (the defacto ideology of the Western ruling class). But I’m not, on principle, opposed to political art that genuinely challenges the prevailing power structure and confronts us with our own limitations in ideology. Lebedev-Frontov was, until the late ‘90s, a member of the Russia National-Bolshevik party. Led by Edouard Limonov and, for a long time, organized by Aleksandr Dugin, the National-Bolsheviks (allow me to be reductive here this isn’t supposed to be a history lesson) held a passionate hatred for Western multicultural liberalism and rejected both fascism and communism but nevertheless extracted ideas and aesthetics from both political formations that they deemed to be worthy. To be more specific, they advocated for both the working class revolutionary spirit of Bolshevism but one that aims towards nationalistic ends for a restored, glorious Russia. However idealistic that might sound, one can’t argue with the fact that the National-Bolsheviks are easily the most aesthetically interesting political group of the last 30 years, with their combination of Bolshevik and Nazi symbols. It was a movement largely led and nourished by dissident artists and thinkers – like Dugin, Limonov, and Lebedev-Frontov. Nevertheless, and true to his ethos as an impossible to pin down Counter-Agent of the Avant-Garde, Lebedev-Frontov soured on and exited the party when he came to see it as politically toothless and castrated. “You know, something similar happened to Italian futurists like Marinetti and Russolo, whose thinking is closest to me, he said in this interview. “They didn’t stay too long in Mussolini’s camp, because when Mussolini really started to set up his new state, the artists and their wild fantasies were no more needed.”

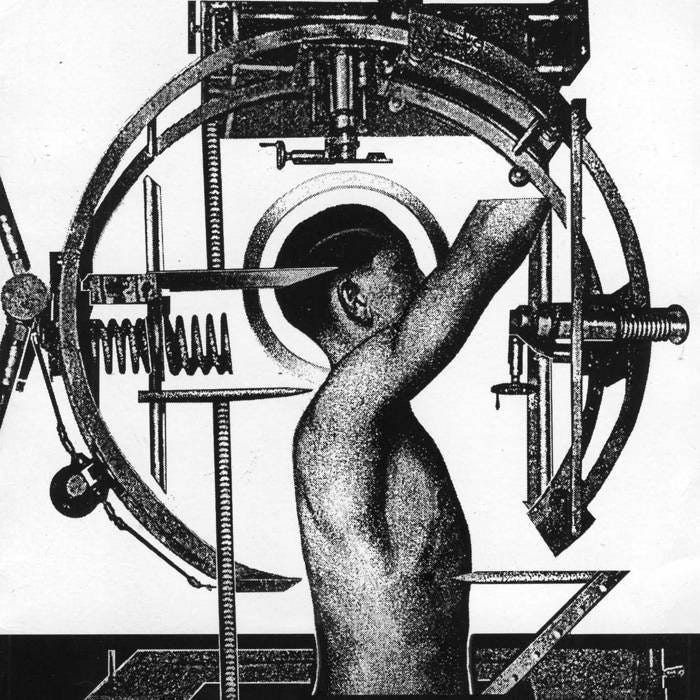

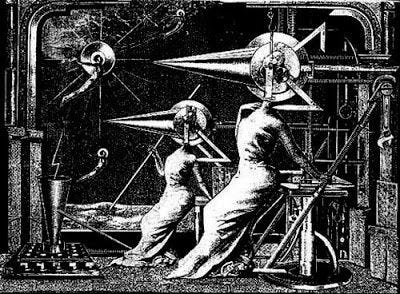

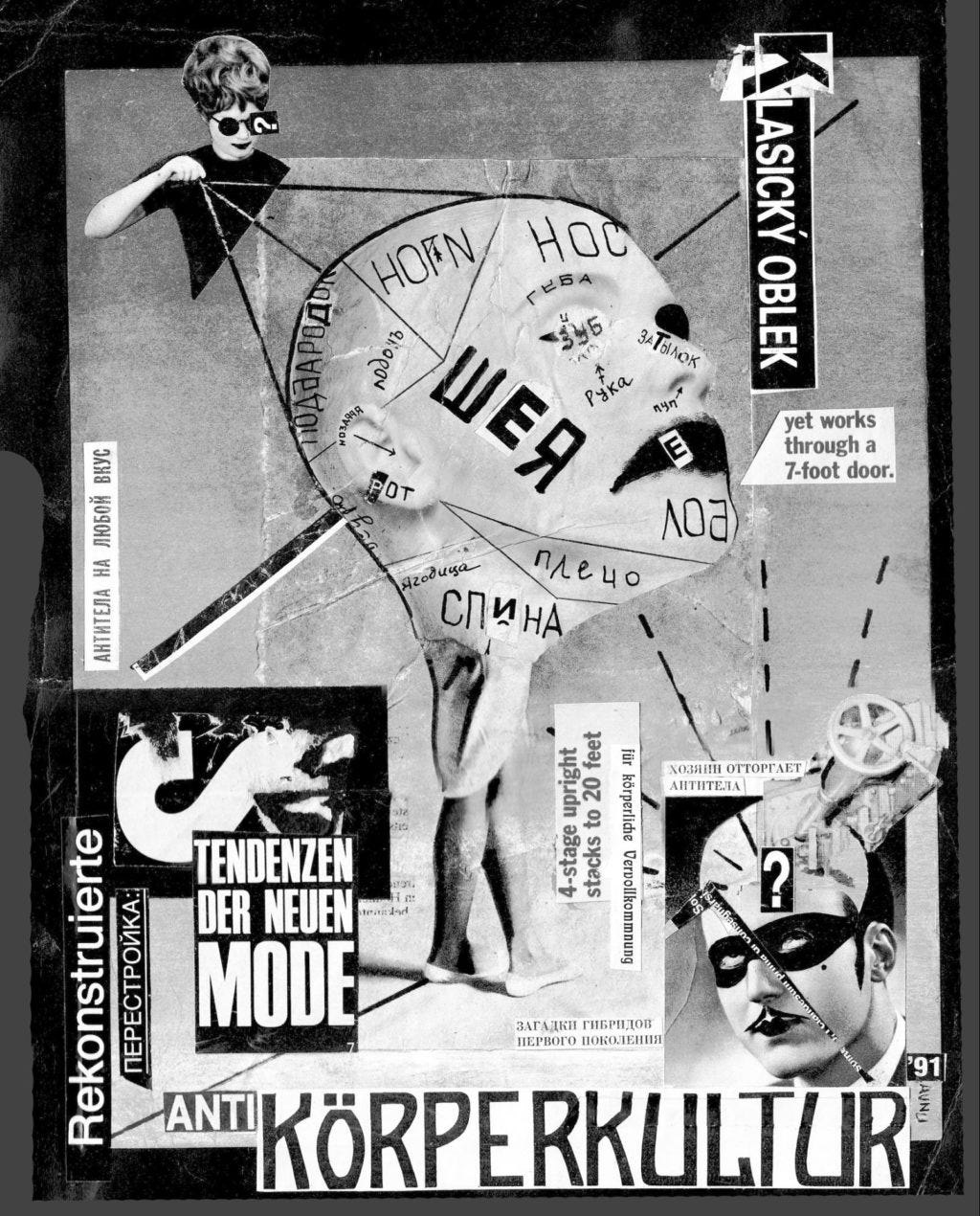

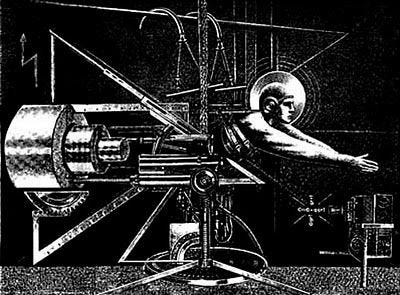

As a visual artist, Lebedev-Frontov works in collage and painting. Always in monochrome, the images evoke Gustav Klutsis’ Bolshevik propaganda posters, Debord’s Situationist collages, and the provocative occultist and fascist imagery that have been integral to power electronics’ iconography since the beginning. This is political art that depicts ideologies as they collide and disintegrate into one another. Looking at Lebedev-Frontov’s is like being punched in the face and violently asphyxiated by my own American liberal conditioning. Political art is, quite often, very fucking gay. But good political art, like Lebedev-Frontov’s, is just great art. And like all great art, it functions as counter-propaganda more than propaganda as such. Lebedev-Frontov’s art is an assault on reductive political defense mechanisms, and evidence of a long and successful career of a truly legendary Counter-Agent of the Avant-Garde.