Visual Propaganda #8: Roland Topor

Surrealistically funny drawings by the Holocaust surviving polymath...

When the Nazis steamrolled France (along with Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) inside of just six weeks in 1940, the country’s Jews were left with difficult choices. Roland Topor, now an icon of cult art, was just a boy when his father was forced to register with the Nazi-controlled Vichy authorities before finally being detained and interned at the Pithiviers holding facility, where most Jews were being held and eventually sent to Auschwitz and the other camps shortly thereafter. Miraculously, however, Topor’s father escaped Pithiviers and hid in the South of France. During that time, the rest of the Topor family lived beneath the paranoia of their venomous Nazi collaborating landlord. The landlord, a cruel old cunt drunk on her minuscule dollop of power, harassed Topor and his sister constantly in efforts to make the two children give up the location of their father. Barely old enough to fully understand the severity of the situation, the children did not waver in their devotion and protection of their father. In 1941, the Topor family was tipped off by neighbors that the Gestapo was going to search their building with the permission of the sadistic landlord. Fleeing to Vichy, the Topor family survived. They even received financial restitution from their landlord for the horrors that she placed upon them and that they endured. An uncommonly happy ending to this anecdote from modern history’s darkest moment.

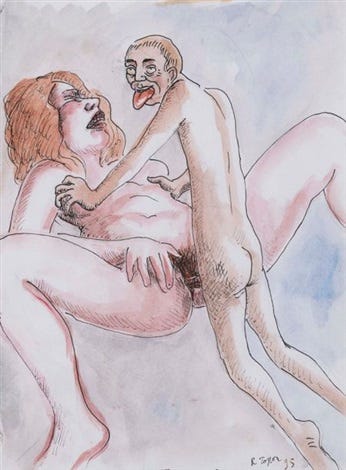

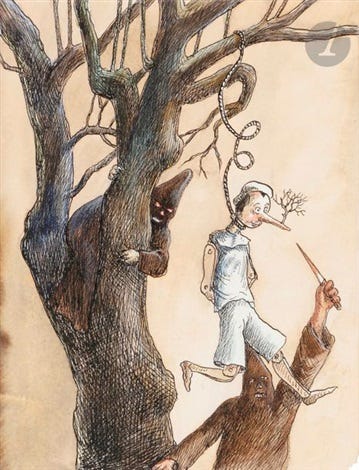

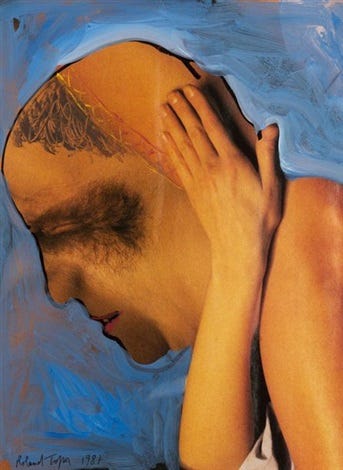

Perhaps his childhood encounters with mankind’s capacity for pure evil is what facilitated the artistic style that Topor would develop as an adult. Working across mediums and disciplines — literature, illustration, painting, theater, and comics — Topor managed to collapse the distance between the horror in tragedy AND the tragedy in comedy. Gifted with a subversive Jewish humor, the macabre in Topor is never absent a touch of hilarity and wit. He understood that surrealism’s absorption into academia and the intellectual vanguard of high art would be its undoing, and his entire career can be read as a full-frontal Counter-Agency insurgency. For Topor, surrealism belonged to the low. To the outsiders, to the degenerates, and to those whom survive.

Along with filmmaker and poet Fernando Arrabal and none other than Alejandro Jodorowsky, Topor co-formed the Panic Movement in Paris in 1961 – a theater movement influenced by Buñuel and Artaud that avowedly attempted to wrestle surrealism away from the mainstream and back to the tender embrace of the cult. The plays were deliberately shocking and violent, exorcising a Dionyisan tendency in often bloody and disturbing ways; in Sacramental Melodrama from 1965, Jodorowsky appeared on stage in a motorcycle jacket, slit the throats of geese, taped snakes to his chest, and was on the receiving end of beatings and whippings. Good fucking time, indeed.

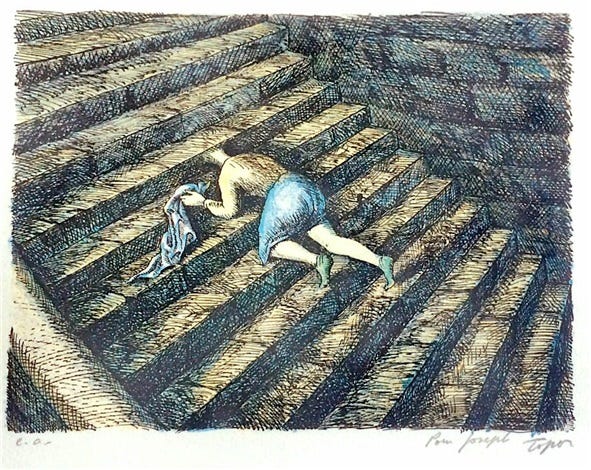

Topor’s best known work is in literature. He wrote dozens of hyper-provocative plays and short stories. But his masterpiece and best known work is the 1964 novel The Tenant, which was adapted into film by Roman Polanski in the mid-’70s. The novel follows a Parisian of Polish descent who slowly finds himself unraveling due to a profound paranoia spurned on by both the aggressive and passive aggressive behavior of his neighbors. One can see a direct connection between the plot of the novel and Topor’s upbringing hiding from the Nazis – few knew the absurd horror that metastasizes when neighbors become your spies and your enemies more than he. “Trelkovsky’s neighbors and everyone else he eventually sees cannot admit to themselves what he comes to realize: everybody is nobody, no one has the power to define themselves,” writes horror master Thomas Ligotti about the novel’s power.

Topor’s drawings are bleak, absurd, and very funny. Intriguingly, he was one of the founders of the Hara-Kiri, the comics magazine that would eventually come to be known as Charlie Hebdo. Oppositional to his colleagues, Topor refused to make traditional comics within the magazine. He wouldn’t even use text bubbles. Instead, all his drawings are a single image that evokes narrative through aura more than it does through storytelling, ever true to Topor’s surrealist ethos. A hand sinks its fingers into a human face. A child lays in a pool of a woman’s blood, perhaps his mother’s. A man looks to the sky while an axe perfectly bisects his head, turning him into a bloody cubist assemblage. The drawings need no explanation. They are what they are.

Cheers to Roland Topor, a pioneering polymath of the Counter-Agency of the Avant-Garde.